Historicizing Freedom and Black Abolitionism

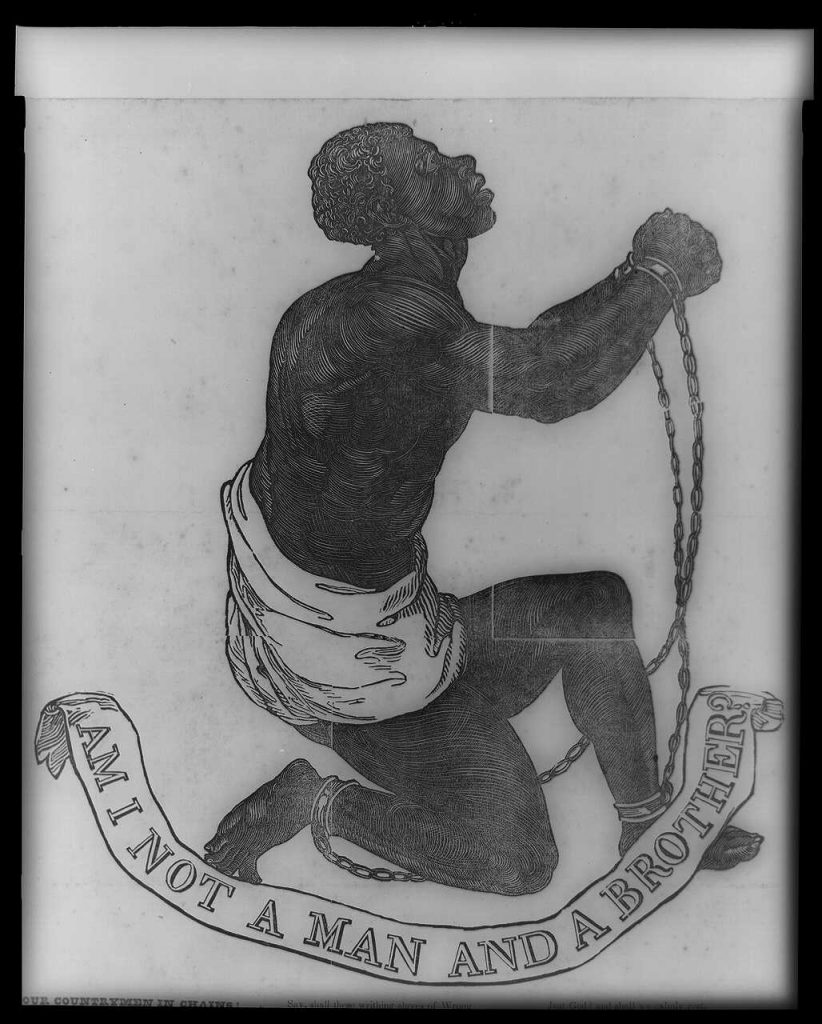

More than a year ago, I wrote about the idea of hope relative to northern black activism during the American Revolution. A panel at the recent national conference of the African American Intellectual History Society about the relationship between black intellectuals and abolition had me again thinking about this issue of black hope, but in a different way. Each of the presenters, Marlene Daut, Vincent Carretta, Yesenia Barragan, and Richard Blackett, presented extremely insightful and thought-provoking ideas that considered the nature of black intellectualism and its relationship to abolition in various eighteenth- and nineteenth-century contexts throughout the Americas and the Atlantic world. Their ideas generated an array of rich conversations revolving around black abolitionist thought and its connections to varied approaches for understanding intellectual labor. Without recounting the ranging conversation, an underlying theme in this discussion related to how we think about the idea of freedom. Any conversation about how hope or optimism animated black abolitionism should approach the idea of freedom as a historical phenomenon that had various and changing relationships to codes and practices of slavery and institutionalized violence.

During the English colonists’ War of Independence, patriots and slaves wrote about and demanded freedom as though it were a transparent idea, simply the opposite of slavery. The black critic Cesar Sarter announced:

…on account of the infringement not only of your Charter rights; but of the natural rights and privileges of freeborn men; permit a poor, though freeborn, African…to tell you…that as Slavery is the greatest, and consequently most to be dreaded, of all temporal calamities: So its opposite, Liberty, is the greatest temporal good, with which you can be blest!”

Yet scholars have revealed the rhetorical dimensions and actual complexities of this distinction. For example, in his recent work Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth-Century Boston, Jared Hardesty explained that by the eighteenth century, slavery in Boston “was a legally defined and codified institution.” The legal boundaries and rules for slavery became institutionalized over time, revealing fluidity even in legal code. Yet, as Hardesty points out, in comparison, the meaning of freedom “was amorphous, ever changing, and defined by its context.” The idea of unfreedom, rather than freedom, reveals that contests of power between bondspeople and the institutions of slavery and oppression always reflected evolving understandings of rights and contestation.

The case of the Massachusetts slave Adam represents a classic example of unfreedom. In 1694, John Saffin, a judge on the Massachusetts Superior Court, promised to release Adam after seven years of service but reneged on this agreement, thus resulting in Adam’s suit. This began a protracted legal and extra-legal battle between plaintiff and defendant. Adam was able to organize a group of whites to testify on his behalf and in May 1703, the Boston Superior Court provided an equivocal ruling. The court declared that Adam should remain free until it be proven that he should be bound. The court did not find Adam to be a slave, but neither did it define him explicitly as free. In consequence of this incomplete ruling, Saffin continued to press his claim. Adam, with the help of others, pushed the direction of the first ruling. In November, the two met in court again, but this time the verdict was clear that Adam was not a slave and could not be enslaved.

This case resulted in a pamphlet war between Saffin and another judge, Samuel Sewall. Sewall published an early and notable indictment of slavery titled The Selling of Joseph: A Memorial (1700). In response, Saffin penned A Brief and Candid Answer to a late Printed Sheet, Entitled, The Selling of Joseph (1701). Slavery occupied the center of this debate, but it was the social change incurred via the increased importation of slaves to New England and not the humanity of slaves or the ethics of human bondage that drove the disagreement. Slavery was called into question, but not primarily on behalf of the bonded and not with the intent of the immediate termination of all human enslavement. Likewise, Adam sued on his own behalf, but not to make a broader legal point about the ethics of condoning slavery. Sewell wrote:

FORASMUCH as Liberty is in real value next unto Life: None ought to part with it themselves, or deprive others of it, but upon most mature Consideration. The Numerousness of Slaves at this day in the Province, and the Uneasiness of them under their Slavery, hath put many upon thinking whether the Foundation of it be firmly and well laid.”

That Adam had won release from bondage meant only that he was free. His individual case and the underlying concerns of the Saffin-Sewall debate demonstrated that slavery could be contested, but that this criticism did not necessarily arise from an absolute and ideological understanding of freedom. As a condition of experience and as a legal category, freedom was vague, contested, and negotiable.

When considering questions of perspective, strategy, and outlook that influenced and arose from slaves’ reactions against slavery, it is important to differentiate freedom as an idea from freedom as an always conditional legal and political position. Rather than arguing for freedom as a natural right, the enslaved of eighteenth-century New England came to understand that freedom itself was being formed from a dynamic mix of context, experience, legal decree and public opinion. Freedom was not just obvious and distinct. The varied and numerous acts of slaves against their bondage highlighted the basic paradox of lifetime servitude: it would always be impossible to treat humans as inhuman in a perfect way. Slaves recognized that acquiring more freedom meant taking advantage of the various tensions and contradictions that arose from the nature of unfreedom.

By the late eighteenth century, even as African American writers increasingly defined the idea of freedom as a natural and hence transcendent political position, they still understood that unfreedom, or degrees of freedom, would continue to define their experience. Moreover, the timing of these black critiques could not have been better, as they sought to take full advantage of the rhetorical potency of shaming a society with slaves.

It was no mistake that black writers and their white allies sought to take advantage of a deepening colonial frustration with British leadership and action. In April 1773, three years before white colonists penned the Declaration of Independence, a group of four black men, calling themselves a “Committee,” wrote “in behalf of our fellow slaves in this province….” This Committee acknowledged being “very sensible that it would be highly detrimental to our present masters, if we were allowed to demand all that of right belongs to us for past services.” They also mentioned “the efforts made by the legislature of this province in their last sessions to free themselves from slavery.” Noting the inconsistency of the colonial government, these writers expected “great things from men who have made such a noble stand against the designs of their fellow-men to enslave them.”

Seeing freedom as a consequence of history rather than as a transcendent goal reframes how we think about black abolition specifically, but also how we think about black intellectual activism more broadly. Of course black people have expressed religious and political views that posit freedom as something that is natural, absolute, and transcendent. However, it is also true that as black people have worked and struggled for more rights and for more equality, they have understood that freedom is something that has to be defined and created. Tracing patterns of hope, optimism, naivety, or pragmatism is certainly useful for understanding black abolitionism. However, it might be best to first consider the parameters of power and discourse that people thought were available to them and that they tried to bend in their favor to become just a little more free.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.