Historians and the Black Freedom Struggle in the North

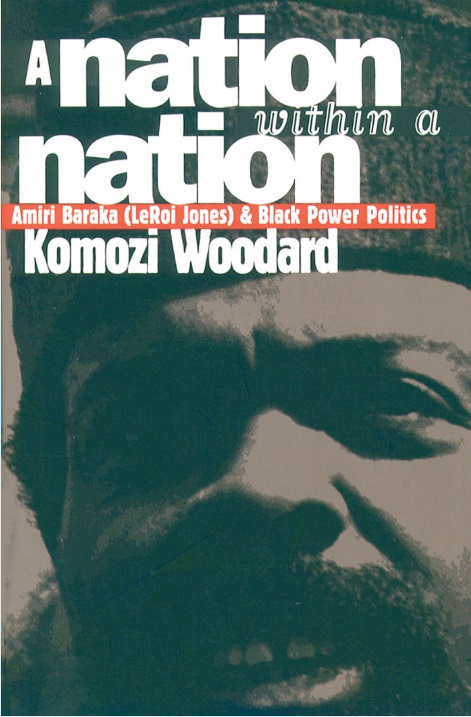

*This post is part of our online roundtable celebrating the 20-year anniversary of the publication of Komozi Woodard’s A Nation Within a Nation

Komozi Woodard’s A Nation Within a Nation: Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) and Black Power Politics changed the study of civil rights by centering the struggle outside the South. A Nation Within a Nation foregrounded the Jim Crow systems in Newark that produced housing and school segregation, job discrimination, police brutality, unequal city services, and an unjust justice system. It showed how to take a publisher’s desire for known, charismatic heroes—in this case Amiri Baraka (which Komozi’s dissertation had not been)—and use it to reveal a broader cast of characters. In doing so, it demonstrated a rich and varied struggle in Newark that did not lag behind nor ruin the Southern one—ushering in what historian Brian Purnell would later term “Freedom North studies.”

The book quite literally helped a whole generation of us imagine how to detail and analyze postwar Black freedom movements across the Northeast, Midwest, and West. It is axiomatic within the historical profession that certain books change the historiography—and thus, it is imperative to trace intellectual genealogies and identify key texts which usher in such rethinking. Other people this week will mark the decisive intellectual influences the book opened in studying civil rights and Black Power, Black Arts, urban studies, and the Jim Crow North. But it wouldn’t do justice to the book without also foregrounding how Komozi himself did so—through mentoring, building institutions, editing anthologies, holding symposiums, and reviewing countless manuscripts in the two decades since its publication. In other words, it is equally crucial to lay bare the “spadework,” as Ella Baker called the daily, unseen, uncelebrated work of social movement organizing, that it takes to change a scholarly field.

Not simply a matter of important ideas rising to the top, opening a field also takes determination, vision, and mentoring. In a profession that is deeply individualistic and often competitive, for twenty years Komozi Woodard has demonstrated that another path is both possible and necessary. It wasn’t enough to get in the door; it required building a doorstop so many, many people could follow. Insisting that intellectual interventions are stronger collectively, he showed how essential telling the stories of Northern Black communities and the movements they built are and that our work as historians is better motivated by love and solidarity.

We need to teach the Northern movement so students can see how much we also loved our children.”—Komozi Woodard

The existence of A Nation Within a Nation enabled me and Matthew Countryman to imagine a panel on Northern struggles at the 2000 American Studies Association annual meeting. We asked him and he immediately said yes. Out of that panel came our co-edited anthology Freedom North. I was a new junior professor at Brooklyn College and he a tenured professor at Sarah Lawrence College, but he made space for my ideas. Saturday after Saturday we sat in a Brooklyn coffee shop, wrestling through the framings for the anthology. What made it hard to see the movements in the North? What changed when we saw them? That segregationists came in Brooks Brother suits as often as they came in Klan sheets; that segregation could be hidden by Northern discourses of “busing,” “cultural deprivation,” and “colorblindness”; that many Northern liberals pushed for change in the South while denying the problem at home; that in the American imagination a sharecropper held a position of virtue that a public housing resident did not and therefore their activism was harder to see; and finally, the Cold War investment in seeing the race problem as a regional aberration rather than a national obsession. These understandings had made their way into popular understandings of the civil rights era, blinding historians to longstanding Northern Black freedom movements.

Perhaps worst of all, because the uprisings of the mid to late 1960s were the dominant way that the North was understood, Black Northerners had been framed as disorganized and different from their heroic Southern sisters and brothers. As the story went, there was little organizing before or after the uprisings. To Komozi, this was one of the most damaging and pernicious beliefs—that Northern Black people were assumed too dysfunctional to build movements. And so a new generation grew up believing their parents and grandparents had not challenged the inequality rife in cities today.

Just like their Southern counterparts, Black Northerners had boycotted, sat-in, blocked traffic, gotten arrested, built independent news sources and organized grassroots institutions. And their efforts deserved the same careful research and analysis Southern struggles were getting. Fundamentally, Komozi believed that putting his work on Newark alongside pieces on New York, Boston, Chicago, Oakland, and other Northern and Western cities was crucial to show that Newark’s segregation was not private or aberrational and that Southern and Northern struggles were contemporaneous and widespread.

Komozi came to academic work by way of years of movement organizing. He was proud that his position at Sarah Lawrence had been won through student organizing. Born partly of his activist vision and community commitments, he refused to see the academy as a zero-sum game where a scholar’s professional success is achieved through individual work. He modeled how we as scholars and thinkers are stronger in our collectivity (hence the work he put into doing anthologies in the wake of A Nation Within a Nation). When he learned that John Dittmer was retiring, Komozi had the idea to honor John by producing a second anthology that showed how the “local people” paradigm had broadened the study of movements from Alabama’s Black Belt to Central Brooklyn—and our second anthology, Groundwork, was born.

Fundamentally what the “local people” paradigm did, according to Komozi, was that it showed how poor and working-class Black people of Northern ghettos like Newark’s had changed history. They made art, critiqued policy, organized neighborhoods, constructed new community spaces, built schools, created countless organizations, made connections internationally and more broadly imagined freedom in multiple ways. They loved their children and their elders, and fought relentlessly for their protection, equal treatment, and liberation. The sum is greater than its parts, he understood, showing how poor Black people organized from the ghettos of Milwaukee to the streets of Oakland would go farther in undermining “culture of poverty” theories which blamed Black culture, rather than structures of inequality, for segregated unequal schools, declining neighborhoods, and Black unemployment.

And when early Black Power studies seemed to be marginalizing the roles of women (even though his personal experience and the work of many scholars we knew said otherwise), Komozi, Dayo Gore, and I published a third anthology, Want to Start a Revolution: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle.

Komozi utilized the space and resources of Sarah Lawrence to help host multiple conferences because he understood that part of what makes it hard to chart new paths is not having a space and resources to gather a community of similarly-focused scholars. Komozi’s organizing and leadership enabled others to take the history farther. It wasn’t enough to put his work out there for younger scholars to use. To him one of the greatest academic sins was how many scholars act too busy for mentoring. Recognizing the people who had opened doors for him (John Dittmer, Mary Frances Berry, and Michael Katz), Komozi opened doors, made introductions, and reviewed countless manuscripts and articles in the twenty years since A Nation Within a Nation’s publication. Dozens of our conversations over the years have begun with Komozi excitedly telling me of some book he was reviewing for some publisher: “I’m behind on my Malcolm X book but let me tell you, I’m reading this really great work … ” And we built the Conversations in Black Freedom Studies series at the Schomburg Center, now in its seventh year, to bring scholars and the public together to discuss new work in Black history.

“We are much more than we are told,” Uraguayan writer Eduardo Galeano observed in analyzing how systems of power constrain the history we are taught. “We are much more beautiful.” Fundamentally with A Nation Within a Nation and his twenty years of field-building and mentoring since, Komozi has shown the beauty and the power of the long Black freedom struggle and what we can continue to do collectively as citizens and scholars.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.