Hip Hop, Masculinity, and “The Get Down”

Why does it seem like hip hop can handle only a handful of prominent female MCs at a time? Roxanne Chante, Queen Latifah, Lil Kim, Lauryn Hill, and Eve were, during their prime, only one of a few. Today, Nicky Minaj and Remy are well-known female MCs. You should also know Rapsody. Where are the rest?

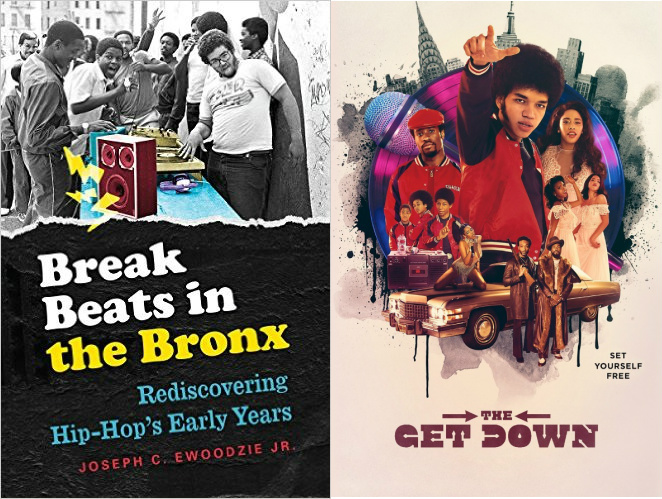

While there is nothing inherently masculine about writing rhymes, rapping, or even creating a beat, hip hop, from its inception, was shaped to be a masculine space. My forthcoming book, Break Beats in the Bronx: Rediscovering Hip-Hop’s Early Years explores precisely how this came to be. It explores several years in the history of hip hop that has surprisingly been ignored—1975 to 1979. It argues that the inner logic of hip hop, including its gendered nature that has lasted to today, was created during this period. It relies on interviews of many unsung heroes from two main sources, a museum and the private archive of a hip hop aficionado, Mr. Troy L. Smith.

In the early 1970s, participants in hip hop had available to them two worlds that proposed contrasting logics of gender and sexuality. In their immediate surroundings in the South Bronx, masculinities and femininities mostly adhered to broader American patterns of patriarchy and heteronormativity. Nearby Manhattan clubs, where disco was king, were sites of gender and sexual logics that differed from the mainstream. During these times, homosexuality was punishable by law, but club goers courageously and defiantly rejected the normalized understandings of gender and sexuality—they subscribed to more fluid notions of each. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual dancers were welcome on the dance floor. After their stand against the police in 1969 at the Stonewall Inn, sexuality became more central to the social identities of these club goers.

Hip hop participants were, in some ways, exposed to these alternative constructions of gender and sexuality from the very beginning, especially since they were participants in an activity shared by both scenes—DJing. However, there is little evidence that they embraced any of these more fluid understandings of gender and sexuality. Netflix’s recent series, The Get Down, highlights these points of contact through Mylene and Shaolin’s involvement in both the hip hop and disco worlds.

Despite these interactions, hip hop performers in the 1970s were mostly male because hip hop drew from several existent social activities in and around the South Bronx, most of which were male-dominated. Men, even young men, generally have more time for leisure activities than women because of gendered socialization processes. While young men in the South Bronx spent hours tinkering with record players, sorting out records, and listening through them for the perfect break beat, young women most likely spent their “free time” at home with their mothers participating in domestic labor. One can also see this in how free time is controlled by parents differently for men and women. Ezekiel and his friends, in The Get Down, are allowed to roam freely while Mylene and her friends are forced to abide by strict curfews.

Relatedly, leisure activities are themselves not gender neutral. They are grounds on which gender stereotypes and gender inequities are reinforced. Although the DJing scene in Manhattan challenged heteronormativity on the dance floor, there were very few well-known female DJs in any of the clubs. Bert Lockett, a butch lesbian who presented herself as male by wearing short hair and a shirt, jacket, and tie, was one of them. “Some of the men didn’t know I was a woman,” she explains. “They would get very angry if they found out I was a girl. I looked like a fella, and they had a problem with that.” From one coworker, especially, she received so much harassment that she eventually quit. “He worked six nights a week, and he was so jealous of my ass he started to tell me what records to play. The audience was saying, ‘They need to get rid of him and let her play!’ In the end, I had to leave that place because he was getting out of hand.”

Gang organizations, from which hip hop drew some of its elements, was also mostly masculine. Some organizations, like the Savage Skulls, had female members, but these women were often the friends, girlfriends, or sisters of male gang members. As a result, their contributions were subordinated. Likewise, the graffiti world included females, like EVA 62 and BARBARA 62, but most were on the scene’s periphery because they had to rely on their male counterparts to traverse the city. “You always have to go out with the guys,” explains LADYPINK, perhaps the most famous of female New York City graffiti writers.

At that time, New York City was very dangerous at night. [Being] a little 15-year-old, 90 pounds, 5’2, [it] wouldn’t be a good idea to go out at night. So I had to go out with a bunch of guys; the night belonged to the men folk.”

What is more, the technology—and the knowledge required to operate it—was more accessible to men than to women. Tricia Rose made this observation years ago Black Noise. “Because [hip hop] music’s approaches to sound reproduction developed informally,” she writes, “the primary means for gathering information [was] shared local knowledge.” Many of the male DJs and MCs learned how to hook up their turntables to their speakers from an older male neighbor across the street or down the hall. “For social, sexual, and cultural reasons,” Rose continues, “young women would be much less likely to be permitted or feel comfortable spending such extended time in a male neighbor’s home.”

Despite the scene’s masculinism, women were not irrelevant to hip hop’s creation. Early participants and interviewees cited in Break Beats in the Bronx explain. “One of the first things I seen in the hip hop music was the girls,” one male attendee observes. “Mad attention from the girls. If you was a DJ or an MC, you had girls. And at the time, being 14, 15, you needed girls.” Some of the male performers were motivated to join the scene primarily by their desire for female attention. Another MC adds, “At the time, I was just a kid from a small town in Jersey, and I’m seventeen trying to get laid and all that kinda stuff, and I had issues about that stuff. I didn’t think I was the best lookin’ guy, so the record was a chance to be who I wanted to be. I wanted to be a ladies’ man in real life.”

If these male actors entered the scene to get women’s attention, they structured it to keep that attention. With the increasing importance of MCing emerged a particular style of rhyming dedicated to wooing women in the audience. “You have guys that write rhymes for battles, and you have some who write rhymes for the ladies,” Grandwizard Theodore explains as he attempts to categorize Kevie Kev, an MC in the L Brothers crew. “Back then[,] I don’t think [Kev] was like a battle emcee; he was like he is going to rhyme for the ladies.” KK Rockwell of the Funky 4 did the same. One of his signature rhymes was: “I’m KK Rockwell and I rock so well, and I like to make love to all the jazzy females.” Keith Keith used this rhyme: “I’m Keith Keith, but you can call me Keith Caesar, the reason why ’cause I’m the woman pleaser.” Likewise, the motivation to look fly was not simply to look cohesive as a crew but to attract the attention of women in the audience. For this reason, a crew would be more likely to admit a well-dressed male into its lineup than an equally qualified male who was less fashion-conscious.

In many ways, hip hop became a masculinized space because it helped the male participants onstage to perform their masculinity, especially their heterosexual desires. And, in many ways, that has not changed, and that contributes to why there are so few female MCs in hip hop. The one’s who make it to the lime light deserve much more credit because they have had to prove themselves as MCs and battle sexism.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.