“Held in Trust by History:” The Intellectual Activism of Lerone Bennett Jr.

On the morning of December 11, 2016, a notice in the Chicago area news read as follows: “Author Lerone Bennett Found Safe After Being Reported Missing.” The 88-year old scholar and journalist had decided to go for an early morning walk, without telling anyone. According to the notice, Bennett had been located hours after he had gone missing. While the news report provided few details about the incident, it indicated that Bennett was “the author of multiple books” who had “previously worked as an editor at JET and Ebony Magazine.” The brevity of this note calls attention to two important facts: that Bennett is not dead as many have assumed, and that he is still largely known for his work at Ebony and for the publication of two critically acclaimed texts even though he produced over ten. While this notice locates Bennett, it fails to account for the extraordinary impact of this important figure.

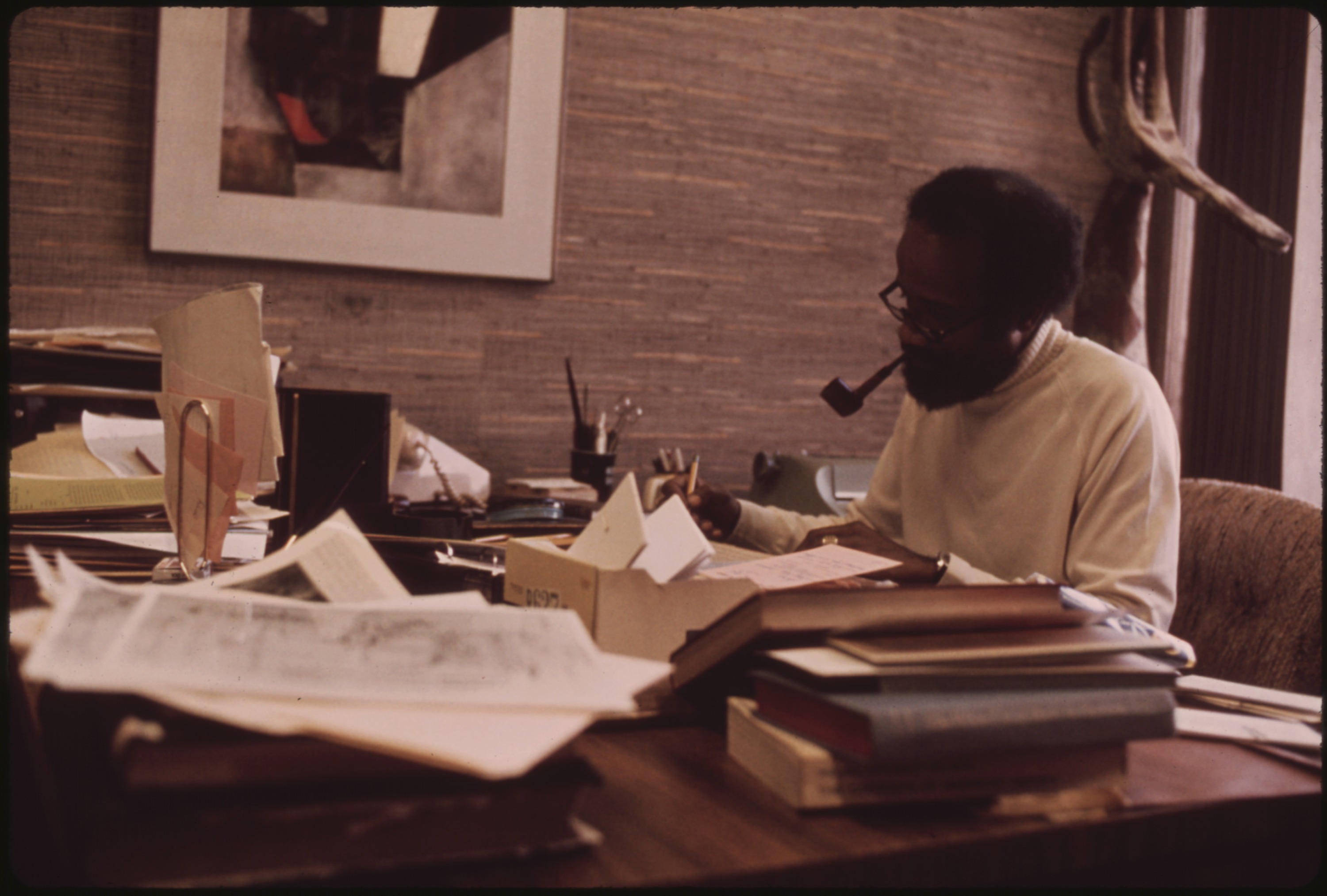

Lerone Bennett, Jr.—social historian, Black Studies architect, and intellectual activist—spent over four decades at Ebony magazine. Ebony, arguably the premier African American lifestyle magazine of the 20th century, was founded by John H. Johnson in 1945. In addition to Ebony, Bennett also maintained a full organizational life, holding memberships and associations in such organizations as the short-lived Black Academy of Arts and Letters, the Race Relations Information Center, the Institute of the Black World, the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, and the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Center. In 1965, John Henrik Clarke was the first to announce Bennett as a social historian and historian Pero Dagbovie revisited Bennett’s influence on Africana Studies in an article in the Journal of Black Studies. Renewing the interest in Bennett’s life opens us to several objectives: to gain a sense of African American historical expertise and craftsmanship, to achieve an expansive definition of intellectual history and the social function of the historian, to contextualize Bennett’s productivity, motivations, and range as a thinker, to achieve a view into his philosophy of life, and lastly to arrive at the creatively disruptive and reparative dimensions of history, all of which are discernible in Bennett’s robust body of work.

Born and bred in the south, Bennett moved to Chicago after a stint at the Atlanta Daily World and was named Associate Editor at Ebony in 1954. Bennett’s time at Ebony was unique. Starting out slowly, he later emerged as one of Johnson’s trusted advisors—he eventually co-wrote Johnson’s autobiography. He used the prestige of one of America’s most successful black entrepreneurs to teach and disseminate black history. The common association of Bennett with the popularizing of history reduces his impact. His record shows that far from watering down the African American experience in the United States, he sought to forge a reparative, justice-centric, visionary account of past human endeavor and the stakes of social disequilibrium. For Bennett, history looks backwards and forwards simultaneously. A brief survey of Ebony issues over this period reveals several principal social concerns, including: African American struggles over rights, passionate interest in the decolonization of the African continent, the uncovering or rediscovering key contributors to Africana intellectual life, and measuring the growing discontent with the prospects of American democracy. On one hand, Ebony emphasized high-life aspiration and on the other it cultivated a devoted and deeply engaged readership. Throughout the 1960s Bennett published a broad range of essays commenting on African American politics, culture, and Afro-diasporic history. Virtually no subject escaped Bennett’s pen. Among the writings in this period are essays on African independence, civil rights militancy, popular culture, and other histories that comprised the series “Pioneers of Protest.”

However, Bennett’s career took off upon the publication of Before the Mayflower in 1962, which began as a series of Ebony essays in 1961. The book was an immediate sensation. Mainstream press outlets such as the Chicago Tribune favorably reviewed the book. The Tribune also carried book reviews written by Bennett while he served as associate editor at Ebony. Historian and activist John Henrik Clarke’s review essay for the black left periodical Freedomways in 1965 locates Bennett in relation to the Civil Rights upsurge carried out by “A new generation of restless black Americans.” For Clarke, Bennett was part of a new generation who, like himself, could be called participant historians. In other words these were historians who not only documented history, but were themselves poised and principled activists in their own regard. Clarke offered readers a glimpse into Bennett’s background before diving into a review of key sections of Before the Mayflower and several of his seminal Ebony articles. Accompanying the piece was two of Bennett’s poems, showcasing a multitalented intellect.

However, Bennett’s career took off upon the publication of Before the Mayflower in 1962, which began as a series of Ebony essays in 1961. The book was an immediate sensation. Mainstream press outlets such as the Chicago Tribune favorably reviewed the book. The Tribune also carried book reviews written by Bennett while he served as associate editor at Ebony. Historian and activist John Henrik Clarke’s review essay for the black left periodical Freedomways in 1965 locates Bennett in relation to the Civil Rights upsurge carried out by “A new generation of restless black Americans.” For Clarke, Bennett was part of a new generation who, like himself, could be called participant historians. In other words these were historians who not only documented history, but were themselves poised and principled activists in their own regard. Clarke offered readers a glimpse into Bennett’s background before diving into a review of key sections of Before the Mayflower and several of his seminal Ebony articles. Accompanying the piece was two of Bennett’s poems, showcasing a multitalented intellect.

The great irony of Bennett’s career, perhaps, is found in his relationship with Ebony, a magazine known for its dependency on advertising that peddled skin lighteners, platform shoes, cigarettes, scotch, the latest styles, and wigs. Bennett was bent on using the popular magazine of the black high life as a reputable platform to document and forecast black struggle, and he succeeded. Still, this did not mean he went unquestioned about what some perceived to be a contradiction.

Without question, Ebony was a critical platform for Bennett. In the front matter of every book he published for JPC, he earnestly thanked Johnson for allowing him the massive platform, time, and resources to research and write. He could reach larger audiences than professors at exclusive colleges or universities, but he could also keep relationships with those institutions that had no effect on his work. Ebony thus emerges as a premier, if unlikely, site of black cultural knowledge production. In this sense Ebony was a different kind of public institution. Bennett certainly benefitted from this unique arrangement and never took it for granted. Not only could he be in the thick of key debates as sage and journalist and historian, but also Ebony’s book publishing gave him a direct line to the national book networks. Among their many publishing pursuits, Bennett and Johnson had plans for an Ebony Encyclopedia.

Bennett’s approach to publishing was methodical and systematic. Lectures and speeches became articles, articles became books, or anthologies. Ebony therefore was unparalleled in its disruption of American consumer trends and U.S. based intellectual work. Bennett had the best of both worlds in terms of institutional credibility among all sectors of the black community. Bennett’s work ethic and standards of excellence had earned him the trust of John H. Johnson. The two carved out what was an enviable relationship. Bennett had access to the publishing mogul, and Johnson needed Bennett’s intellectual heft to bolster the magazine’s reputation and commitment to sincere and earnest coverage of black life beyond the simple demands of capitalist advertising and an aspiring black middle class’s pursuit of the high life. But Johnson was no fool. And although he refused to wear his politics on his sleeve, Bennett viewed Johnson as a sincere and chief advocate of black life. Effectively, Bennett was the bridge across a full spectrum that stretched from a petty capitalist, black bourgeoisie, churchgoing, assimilationist community, to grassroots militants and middle- and working class intellectuals with nationalist proclivities, alongside full expressions of black elite aspiration. No matter the segments of the black community and their ideological shadings or capitalist accouterments, in Bennett’s view, their fates were linked, and, moreover, they all had to answer the call of history and the demands of time.

At the turn of the 21st Century, Bennett remained active. On April 26, 2000, Bennett testified in front of the “Joint Hearing of the Finance and Human Relations Committees of the Chicago City Council on Reparations for African-American Slaves and Their Descendants.” The sage historian took full advantage of the opportunity to underscore the unpaid debt long past due. Interestingly, atop the typed speech, in Bennett’s cursive handwriting are the words, “Held in Trust by History.” It was as if Bennett was reminding himself of the duty to once again shine due light on the evidence and make the case plain.

Like W.E.B. Du Bois and Carter G. Woodson, he showed a commitment to “living history” and modeled a kind of public intellectualism that was both strident and sensitive. His time at Ebony suggests that a popular media platform could just as easily become a classroom. For Bennett, history was not just a discipline–it was obligation, memory, and art. He was moved by the opportunity, calling, and challenge of doing good work on behalf of a people’s struggle. Lerone Bennett, Jr. no longer needs an “All Points Bulletin/Missing Persons Report.” He has been here the whole time.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thanks for this. Bennett is a true pioneer–a brilliant writer and a crusading public intellectual. Respect!

Wonderful. Thank you for reminding us of him and his work.

Thanks so much for sharing this wonderful piece with Black Perspectives.

Historian/Brilliant Writer Bennett has honored our history and deserves accolades of the highest level…a pioneer providing truth and substance.

Great article Chris! I’d be interested to hear your thoughts about the limitations of Bennett’s historical writing – particularly regarded his heavily gendered understanding of black history’s form and function – as well as his short lived time as the founding chair of Northwestern’s Afro-American studies department

Thanks, James. Here are some brief thoughts on your questions. 1. It is clear that when Bennett wrote history it was for the benefit of black people in part and in whole. I think a look at his speeches in addition to his published works gives a fuller picture of bennett’s thinking on form and function of black history. If you mean that he ignored women in his writing I’d certainly suggest a close look at his speeches—many of which were unpublished; his dedication to black women is found in the opening pages of “before the mayflower”; he was in the process of writing a family history that traced his lineage through his grandmother and gave numerous speeches in which she was the subject—one recognition he received at the University of Mississippi he entitled Lucy Reed’s award in her honor, suggesting that accolades bestowed upon him were not his alone; he was a mentor to many historians, men and women alike. At the 1980 Cornell Africana Studies commemoration he shared the platform with a young black woman historian named Bettye Thomas, along with Robert Harris and Vincent Harding. In that speech he argued, “Black history is a totality in the process of becoming. It is the sum total of the micro- and macro-projects of all Black people;” he was on the editorial staff with longtime journalists Phyl Garland, and Era Bell Thompson, and each appear to have had a respectful relationship with Bennett and he with them; much later he was also at work on a “Lerone Bennett Reader” in which several sections dealt with black women activists, leaders, and trailblazers like Lucy Reed, but also well-known names such as Rosa Parks and Mary McLeod Bethune, for example. The longer version of my work on Bennett engages this discussion. That said the entire historical profession has failed to fully cultivate and develop the talent and historical writing of women historians until very recently. This is not to say that there weren’t gaps and controversy in Bennett’s published work or that he was impervious to patriarchy, but more needs to be uncovered to suggest that he ignored gender as a specific category of historiography. It would appear however that relative to the profession Bennett’s body of work was far ahead of the curve in terms of acknowledging black women’s indelible mark on his personal life and the historical record.

2. Chapter 3 of Martha Biondi’s black revolution on campus discusses Bennett’s short but contentious tenure at Northwestern–you have thoughts on her discussion of the events?

Hi Chris, thanks so much for your thoughtful response. I didn’t mean to suggest Bennett ignored black women in his writing – as you say, this is something which isn’t born out in both his writing inside and outside of EBONY, as well as his public addresses. Rather, i was referring to the ways in which his writing helped to reinforce a patrilineal vision of black history, and the connections he drew between black history, masculinity, and liberation (arguably seen most clearly through his speeches for the Institute of the Black World).

In my own writing on Bennett i have sometimes described him as an ‘antiracist patriarch’ – I’d be interested to hear your opinion on this categorisation. Often this was reinforced by his environment; as you state, Bennett had a strong relationship with black female journalist such as Thompson, however the editorial hierarchy of Johnson Publishing remained heavily biased towards the work of black male writers and journalists.

With regards to Biondi’s work, i would broadly agree with her assessment of Bennett’s time at Northwestern, although I would add that since the publication of her book a number of important new archives have come to light which shed further light on Bennett’s relationship to the University.

You mentioned a longer version of your work. I’d be very interested to read it. Is this something published or which you are currently working on?

Thanks for the wonderful piece on Lerone Bennett, Jr.–a genuine public intellectual in the contemporary vernacular, and I contend that he merits recognition as an intellectual historian also; while Bennett is mostly known–and rightly so–for his “Before The Mayflower: A History of Black America”, his two publications, “Pioneers in Protest” and “Confrontation:Black and White” are superb and incisive analysis of the historical trajectory of African American thought in the freedom struggle, and his elegant portraiture of the principal African American men and women who harnessed these thoughts and ideas with actions deserve a space on the book-shelf of any African American history library–I still cherish my heavily underlined paperback editions.

I really hope that some enterprising and intellectually curious graduate student somewhere is hard at work on the “Collected Writings of Lerone Bennett, Jr.: A Profile Of an Activist Intellectual.”

thanks, carl. bennett certainly deserves a fuller and up-close look. this short piece was an entry point.

Bennett is my favorite non-fiction author. “Before the Mayflower” is the work that has most influenced my (and my family’s) politicization since age 12.

He is truly a giant among men and historians.

THANKS for this article! (And for the great intellectual discussion I’ve seen in the “Comments” section!) This is the article I’ve always wanted to read about Bennett, a person I consider a professional role model.

I think his “Shaping of Black America” is both the Gold Standard and a greatly unappreciated work.

I know that James West is working on his book. This article well satisfies my hunger until that day.