Head Start and Mississippi’s Black Freedom Struggle: An Interview with Crystal R. Sanders

This month, I interviewed Crystal R. Sanders about her new book, A Chance for Change: Head Start and Mississippi’s Black Freedom Struggle (University of North Carolina Press, 2016). Dr. Sanders is an Assistant Professor in the Departments of History and African American Studies at Pennsylvania State University. She was born, raised, and educated in North Carolina where she remained until graduate school. She earned her B.A. degree in History and Public Policy at Duke University and her M.A. and Ph.D. in History at Northwestern University. Her research and teaching interests include the history of black education, black women’s history, southern history, and black freedom studies. Her work can be found in the Journal of Southern History, the North Carolina Historical Review, the Journal of African American History, and the History of Education Quarterly. She has received numerous awards and honors including the C. Vann Woodward Prize from the Southern Historical Association, the Huggins-Quarles Award from the Organization of American Historians, a Ford Dissertation Fellowship, a Spencer Dissertation Fellowship, and a fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She is working on a new book project that explores black southerners’ efforts to secure graduate education during the Age of Jim Crow.

This month, I interviewed Crystal R. Sanders about her new book, A Chance for Change: Head Start and Mississippi’s Black Freedom Struggle (University of North Carolina Press, 2016). Dr. Sanders is an Assistant Professor in the Departments of History and African American Studies at Pennsylvania State University. She was born, raised, and educated in North Carolina where she remained until graduate school. She earned her B.A. degree in History and Public Policy at Duke University and her M.A. and Ph.D. in History at Northwestern University. Her research and teaching interests include the history of black education, black women’s history, southern history, and black freedom studies. Her work can be found in the Journal of Southern History, the North Carolina Historical Review, the Journal of African American History, and the History of Education Quarterly. She has received numerous awards and honors including the C. Vann Woodward Prize from the Southern Historical Association, the Huggins-Quarles Award from the Organization of American Historians, a Ford Dissertation Fellowship, a Spencer Dissertation Fellowship, and a fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She is working on a new book project that explores black southerners’ efforts to secure graduate education during the Age of Jim Crow.

***

Keisha N. Blain: How did you come to this topic? What are the factors and/or motivations that led you to write a book on Head Start and Mississippi’s Black Freedom Struggle?

Crystal R. Sanders: I have had an interest in the history of black education since I was a child. My young mind often thought about the discrepancies between what my parents and grandparents told me about their experiences in black schools during the era of legal segregation and what I was told about black schools as a student in elementary and middle school classrooms. I wrote an undergraduate honors thesis in an attempt to push back against the dominant narrative that black schools pre-Brown were substandard, underfunded institutions. To the contrary, I found that many of these schools functioned as community sources of pride that nurtured black students and helped them to reach their highest potential. I learned that black parents and grandparents “double-taxed” themselves to ensure that black students had what they needed to be successful.

Writing an alternative narrative about black elementary and secondary education awakened a scholarly passion for black education within me. I then went on to graduate school and wrote my master’s thesis about a protest that Howard University students led in 1934 to challenge segregation in the House of Representatives dining hall. While searching for speeches in the Congressional Record related to the Howard protest, I stumbled upon a 1966 speech given by United States Senator John C. Stennis (D-MS). Senator Stennis took to the Senate floor to oppose the Child Development Group of Mississippi (CDGM), a statewide Head Start program that he maintained was a front for communism and black militancy. His sensational language piqued my curiosity so I began looking for more information about CDGM. I asked myself “What could be so radical and subversive about a program for preschoolers?”

The more digging I did on CDGM’s program, the more obvious it became to me that black education at all levels—including early childhood education—is political and contested. I was struck by how black women throughout the Magnolia State mobilized to bring preschool programs to their children in the same ways that black men and women had nickeled and dimed elementary and secondary schools into existence decades earlier. Also of interest was the fact that many of the individuals connected to CDGM had played integral roles in the state’s freedom struggle. Head Start simply became their next battleground in a much longer war waged for full freedom.

Blain: Tell us more about the inspiration for your book title, A Chance for Change. Where does the title come from and how does it reflect the major argument and themes of the book?

Blain: Tell us more about the inspiration for your book title, A Chance for Change. Where does the title come from and how does it reflect the major argument and themes of the book?

Sanders: I wish that I could say that the book’s title came to me in a moment of creative brilliance, but that is not true. As CDGM experienced refunding delays because of segregationists’ opposition to the program, program staff and parents made a video to be used for fundraising purposes. The video, which explored all of the benefits that CDGM provided to working-class black children and their families, was titled A Chance for Change.

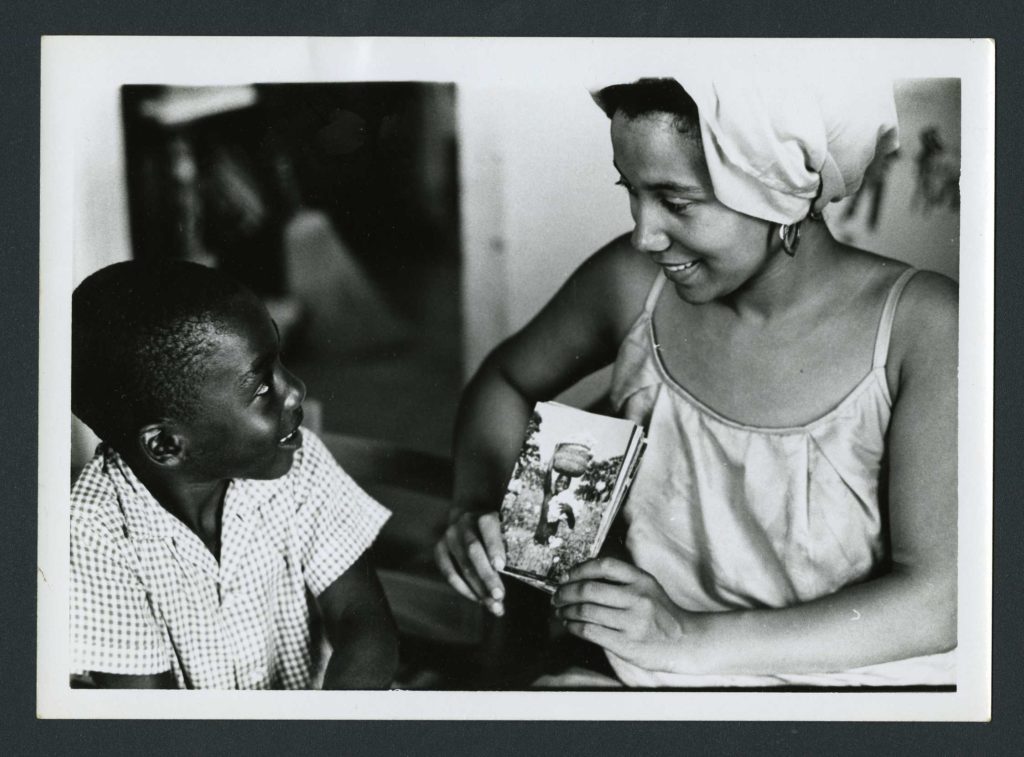

The title is most appropriate for my book because Head Start offered both young and old black Mississippians a chance to change their educational, political, physical, and financial destinies. The early childhood education program provided black children with access to professional healthcare, nutritious meals, and an education that celebrated rather than condemned their blackness. The program afforded working-class black Mississippians well-paying jobs outside of the local white power structure, the chance to complete the educations that had been denied them, and the opportunity to control something other than their homes and churches. CDGM truly was a chance for change.

Blain: Your book offers a new and original perspective on the Head Start Program, providing a bottom-up view of the War on Poverty and centering the ideas and activities of ordinary men and women in Mississippi during the 1960s. Tell us more about how working-class black Mississippians envisioned Head Start as both a means to bolster their political standing and improve their socioeconomic status.

Sanders: The book introduces readers to many unheralded civil rights activists in the state of Mississippi. Many of these activists were women and I tried to convey their spunk, bravery, and commitment with my prose. When told about the availability of Head Start funds in 1965, Mrs. Lavaree Jones, a black woman from the Mississippi Delta, exclaimed that the program was “the answer to a prayer.” All too often, scholars of the movement do not ask what happened to local people in Mississippi after Freedom Summer…after the media left the state and northern white volunteers returned to their homes. Black Mississippians continued to face white lawlessness and white recalcitrance toward civil rights. Many, like Mrs. Jones, had lost their jobs because of their activism. Their kids still attended segregated schools despite the fact that the United States Supreme Court had ordered otherwise in 1954.

Working-class black Mississippians understood that civil rights legislation alone could not improve their plight. Many, then, purposed to exploit Head Start, a community action program that mandated their meaningful participation, to secure quality education for their children and professional employment opportunities for themselves. Head Start in its initial years did not require teachers to have formal credentials. This mean that men and women who had worked as cotton choppers on white-owned land or who had labored as domestics cleaning white homes now had the opportunity to work for a Head Start program. Head Start employment distanced these local people from the oversight of local whites who often used economic reprisals to curtail activism. Thus, it is no coincidence that many of the first black Mississippians to enroll their children in previously all-white schools in the fall of 1965 were CDGM employees. The preschool program was indeed an answer to prayer.

Blain: In Chapter 2, “A Revolution in Expectations,” you argue that the Child Development Group—the Head Start Program that gave impoverished black children greater access to early childhood education—“built upon and extended earlier civil rights work in Mississippi” (p. 71). Can you elaborate on this point?

Sanders: The fight over Head Start in Mississippi was part and parcel of a much longer struggle for African Americans’ full freedom. Dating back to the Reconstruction era, white officials in the state underfunded black education to limit black Mississippians’ employment options later in life. James Vardaman, who served in the U.S. Senate and as Mississippi’s governor, once said that educating African Americans “is to spoil a good field hand and make an insolent cook.” Moreover, the state’s white power structure controlled, limited, and filtered what black students learned. Black teachers who mentioned black history or discussed Emmett Till in the classroom faced termination. African American parents fought back but remained powerless to bring about significant changes since disfranchisement devices such as literacy tests prevented them from voting.

Because of the dismal black educational status quo in Mississippi, black parents rallied around Head Start. As a federal program, local white officials could not control Head Start’s funding and could not dictate what was taught in Head Start centers. CDGM offered black parents the opportunity to provide their children with an education that celebrated blackness and that was devoid of inferior resources. In doing so, CDGM bore witness to the parents who had advocated for better funding for black education since the late nineteenth century. The program also provided an opportunity for working-class black Mississippians to participate in community governance since electoral politics continued to be closed to many. Ordinary black men and women sat on Head Start committees that functioned as pseudo-school boards. They made decisions about everything from where a CDGM center was located to which vendors supplied food and toys.

Blain: One of the significant aspects of your book is its focus on the experiences of black women in Mississippi during the modern Civil Rights Movement. Tell us more about how Head Start fundamentally altered black women’s political and economic prospects during this period.

Sanders: As Charles Payne’s seminal work on the Mississippi Freedom Struggle showed us, black women “canvassed more than men, showed up more frequently at mass meetings, and more frequently attempted to register to vote.” Remember, it was Fannie Lou Hamer who went to the courthouse to vote in 1962—not her husband Pap Hamer. In a state like Mississippi that worked to preserve white supremacy by any means necessary, there were consequences to challenging the racial status quo. Black women were central actors in the fight to dismantle white supremacy and they faced white reprisals because of their political work.

Black women outnumbered black men in CDGM. This was so for a variety of reasons including the fact that women are the normative caretakers for children and because women more readily saw Head Start as a continuation of their earlier civil rights work. In the book, I show that CDGM jobs were critical in restoring the economic livelihoods of black women who had lost their jobs because of their activism or because of their proximity to the movement. For example, Roxie Meredith lost her job as a school cafeteria worker in 1962 after her son, James, desegregated the University of Mississippi. Roxie Meredith did not have steady employment again until she secured a CDGM job.

For certain, CDGM did much more than employ black women. The program provided these women with professional employment. CDGM supposed that former sharecroppers and domestics had the ability to learn on-the-job and thus gave them the chance to gain valuable work experience in office and educational settings despite lacking formal credentials. Additionally, Head Start paid for many of these women to return to school and complete their educations.

Blain: Your book significantly enriches our understanding of black education in the United States. Where do you think the field is headed? What areas would you like to see further explored? How does your next book project address some of these concerns?

Sanders: Black education in the United States is such a rich subfield and yet, there is much work left to be done. I would love to see studies about the experiences of African students who enrolled at black colleges in the 1920s and 1930s (e.g. Nnamdi Azikiwe and Kwame Nkrumah). I would also like to see more work on the lived experiences of African American college students at historically black and predominately white institutions throughout the twentieth century. My next book project takes up the latter task. I am exploring black southerners’ efforts to secure graduate education during the age of Jim Crow. For the first third of the twentieth century, southern state legislatures did not provide any graduate education for African Americans. Rather than create graduate and professional programs at black colleges or desegregate white colleges, southern state legislatures appropriated tax dollars to send black citizens out-of-state for graduate training. This practice continued even after the United States Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional in Missouri ex rel. Gaines V. Canada (1938). For example, North Carolina began an out-of-state grant program for black students in 1939. Mississippi implemented its own “Jim Crow scholarship program” in 1948. I aim to shed new light on the high financial costs of segregation and to expose the forgotten sacrifices and struggles of thousands of African Americans who left their families and communities in search of educational opportunity.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Sensational scholarship! So, so imperative to understand, if we are to continue our struggle.

BlackStudies.site