Haunting Harmonies: Filmic Sounds in 12 Years a Slave and The Birth of a Nation

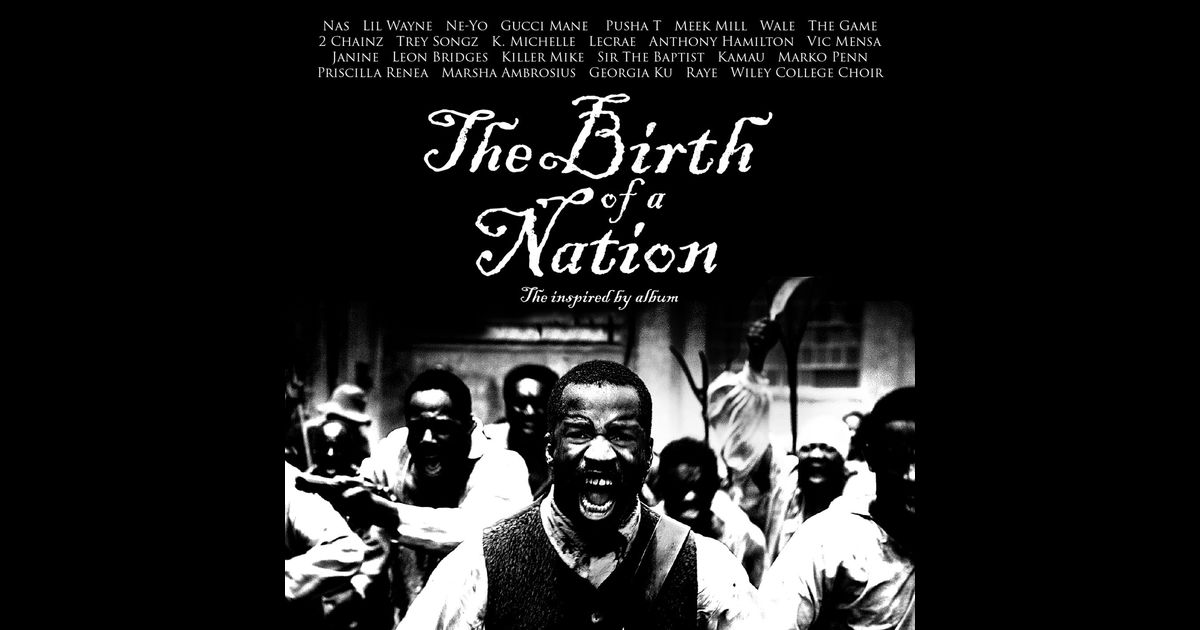

The recent release of The Birth of a Nation (Fox Searchlight, 2016) has resulted in a surprising blaze of dissonant claims about the overall value of the film (or lack thereof), its cinematic innovation (or lack thereof), its historical accuracy (or lack thereof), its compelling presentation of black religion (or lack thereof), and its comprehensive representations of gender (or lack thereof).

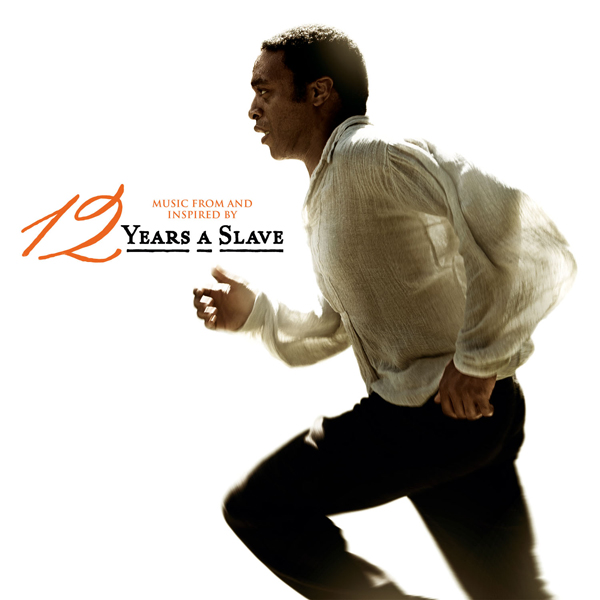

The firestorm surrounding this film, while much more vitriolic and divisive (and directed largely at director Nate Parker because of his role in a now highly publicized sexual assault case), parallels some of the discourse surrounding the release of 12 Years a Slave (Fox Searchlight, 2013). Here on AAIHS, Ibram X. Kendi and Deirdre Cooper Owens have added their voices to a complex chorus debating the time and space where race, gender and popular culture intersect. Though we may not remember it as well, there were several similar controversies surrounding the release of 12 Years a Slave three years ago.

I experienced both films in the theater during their live runs. I saw them both out of my interests in unpacking the intersections of black religion and gender laid bare (or made invisible) within popular film. I also watched them in large part because my scholarship requires that I engage filmic texts, and especially so when the discourses surrounding them are steeped in controversy. In the midst of my viewings and the controversy, I have not forgotten a fundamental premise of what popular films are meant to do: to provoke.

There is a great deal to be said about the cinematic similarities between 12 Years a Slave and The Birth of a Nation, including the significant role of black religiosity (which in both films is not exclusively Christian), and their complicated representations of black womanhood. I fully intend to engage these matters, which require more substantive engagement than space currently allows. As period dramas adapted from true events, their protagonists’ share narrative arcs from naïveté, to resignation, to resistance, and finally to deliverance. For Solomon Northup, (Chiwetel Ejiofor) deliverance arrived when he escaped from bondage and regained his freedom. For Nat Turner (Nate Parker) deliverance arrived in the form of death, where he was publicly hung for his part in inciting a rebellion.

In terms of cinematography, the use of canted angle and close ups by directors Steve McQueen and Nate Parker effectively convey important shifts in the protagonist’ experiential lens. Their parallel diegetic framing indicate the importance of depicting the most brutal aspects of enslavement imaginable. These films both capture aspects of black survival and resistance during some of the most inhumane times imaginable for black people on American soil.

What has not been discussed nearly as much, or as enough, are the ways that two films— controversies withstanding—use the music of an era. In both films, music acclimates viewers to the protagonists’ tumult and despair, and awakens viewers to the significance of music—namely spirituals—as a mechanism to survive the brutalities of enslavement. Music also provokes visceral emotive responses, and most notably, music haunts us.

The songs in these films warrant their own substantive engagement. Two stand out, however, for the ways their filmic placement calls our attention to a pivotal moment in the film, taps into our emotional sensibilities, and haunts with a reminder of the never-ending tension of despair and hope for black Americans. The first is “Roll Jordan Roll.”

Roll Jordan roll,

Roll Jordan roll,

My soul arise in heaven lord,

for the year when Jordan roll

In 12 Years a Slave “Roll Jordan Roll” signals an end to Solomon Northup’s quest for freedom, and a beginning state of resignation toward his status as an enslaved man. The song, which is performed after Northup witnesses a man drop dead in the cotton field, reveals his internal conflict. Northup is initially reluctant to sing, but eventually fervently joins in with the collective of enslaved men, women, and children.

Similarly, the placement of “Couldn’t Hear Nobody Pray” as performed a cappella by the Wiley College Choir conveys how despair and death collide in The Birth of a Nation, even as they lead to freedom. As Nat Turner hangs the intonation of vocal humming, the tempo of shuffling, stomping feet, and the filmic fade to black effectively convey the desolation of black existence. It is a poignant reminder that regardless of the end, we all encounter death alone.

I couldn’t hear nobody pray

way down yonder by myself

I couldn’t hear nobody pray

With their eighteenth century origins and deep Methodist roots–“Roll Jordan Roll” was written by Charles Wesley and Wiley College is a historically black Methodist institution–both songs have a powerful effect on the viewer. Through vocal ingenuity, we are haunted by a shared, collective memory of the power of music to provoke us to feel the depth and range of black experience.

It remains to be seen how broadly these films—and especially The Birth of a Nation—will be received. In the end, whether or not these films garner the financial support they project, it is my hope that viewers will experience the ways in which these filmic soundtracks tell their own stories, offer up their own expressions of despair and hope, and resonate in black freedom.

LeRhonda S. Manigault-Bryant is Associate Professor of Africana Studies at Williams College. She is the author of Talking to the Dead: Religion, Music, and Lived Memory among Gullah/Geechee Women (Duke University Press), and co-author of Womanist and Black Feminist Responses to Tyler Perry’s Productions (Palgrave Macmillan) with Tamura A. Lomax and Carol B. Duncan. Follow her on Twitter @DoctorRMB

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.