Harold Cruse’s Ruthless Criticism

*This post is part of the Society for U.S. Intellectual History’s recent roundtable on Harold Cruse’s The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual (1967). Click here to read Robert Greene II’s introduction to the roundtable.

In 1961, Harold Cruse submitted a long article to the hot new Madison-based lefty journal, Studies on the Left. The article, “Cuba, Marxism, Nationalism, and the American Negro,” which argued in part that Black Americans could learn more from Cuban revolutionaries by studying their nationalism—as opposed to their Marxism—was eventually published by Studies. But the journal’s editors only decided to publish the piece after some serious intellectual soul searching.

Serious intellectual soul searching for the Studies editors often took the form of verbal high jinx, especially when the indomitable Ellie Hakim was involved. In an unsigned scathing review of Cruse’s manuscript (which I suspect was written by Hakim), his prose was described as replete with “the circular verbiage (rhymes with garbage) of nationalism.” In short, these young white New Leftists, whose vision of the good life was grounded in Marx or Emerson—sometimes both—had difficulty seeing the value of a social philosophy based on the ideas of Malcolm X.

But, since Studies was sincere in its effort to forge a capacious “new” left, it was open to articles that challenged old left pieties. So, it published Cruse, nationalism and all.

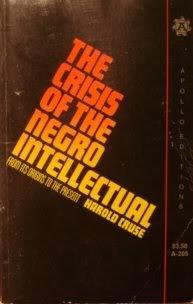

On the flip side, Cruse was not your typical Black nationalist. As a former member of the Communist Party, he arrived at Black nationalism circuitously. This helps explain the atypical character of Cruse’s remarkable literary achievement, his 1967 mammoth book, The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, which this roundtable is commemorating on its 50th birthday.

To describe Crisis as atypical hardly begins to do it justice. We might call the book an intellectual history of Black radicalism from the 1920s to the 1960s, but this too hardly begins to do it justice. Crisis is an eclectic set of essays about an array of topics, ranging from the Harlem Renaissance to Richard Wright to the Communist Party to violence. But the book cannot be reduced to a set of snapshots, either.

Perhaps it is best to say that Crisis is “a ruthless criticism of all that exists.” Cruse pulled no punches in offering withering critique after withering critique—of Black intellectuals, Black artists, civil rights liberals, integrationists, communists, socialists, and even his fellow Black nationalists. Cruse thought Black radical intellectual life was a complete mess. The only way to begin cleaning it up was through clearheaded if harsh criticism.

Fashioning identity politics as realism, Cruse’s central point can best be summed up in the following passage from Crisis:

The individual Negro has, proportionately, very few rights indeed because his ethnic group (whether or not he actually identifies with it) has very little political, economic or social power (beyond moral grounds) to wield.

But what did Black intellectuals have to do with this problem? Why was it their crisis? Cruse contended Black intellectuals from the Harlem Renaissance to the Civil Rights Movement had failed to give Black Americans solutions to their problems because they had not developed an independent Black radical culture.

Blacks would never achieve freedom in the United States—in white America—if they did not first build their own institutions. By declaring the need for institution-building, Cruse did not limit his scope to political and economic institutions. He also argued that Black freedom required independent Black cultural institutions. This is where intellectuals came in. “The special function of the Negro intellectual,” Cruse wrote, “is a cultural one.” Blacks had to believe they could be free, but such a belief could only take root if Blacks had their own cultural institutions—theaters, newspapers, schools, etc. By working in racially integrated cultural settings and institutions—or worse, by working for white cultural patrons—Black intellectuals had been unable to attain the cultural independence that was a necessary precondition of Black freedom.

Based on the description of Cruse’s argument that I have given thus far, readers might wonder what makes Crisis different from any of the other Black Power texts that emerged from the late 1960s. How is Crisis any different from Stokely Carmichael’s and Charles Hamilton’s Black Power: The Politics of Liberation, also published in 1967? Sounding like Cruse, Carmichael and Hamilton wrote: “Group solidarity is necessary before a group can effectively form a bargaining position of strength in a pluralistic society.”

Cruse’s book was different for at least three reasons. First, Crisis is not celebratory Black nationalism; it does not trade in myth. Cruse criticized everyone, including Langston Hughes, Marcus Garvey, and many more hallowed figures.

Second, in addition to being a history of Black intellectuals, Crisis is also a deeply learned history of the American left, or of what Cruse would have considered the white left. How many other Black nationalist writers were well grounded in V.F. Calverton of all people? How many other writers, period?

The third reason that Crisis stands out among the Black nationalist literature—related to the second—is that Cruse outlines a plan not only for Black intellectuals but also for American Marxism. Cruse argued that the Marxism pitched by the American Communist Party, including the party’s Black members, was based on ideas that were alien to the American masses. Marx and Lenin had no purchase on American political life. One of the reasons Cruse admired Calverton, editor of the independent Marxist journal Modern Quarterly, which was in print from 1923 to 1933, was because Calverton had long been highly critical of the notion that European Marxism, filtered through Russia, could help build a left in the United States.

Cruse was not necessarily opposed to the idea of an American Marxism, but in building on insights gleaned from Calverton he contended that if effective socialist theory was going to sprout on native grounds, it had to be planted by Black intellectuals. As Du Bois said in a passage approvingly quoted by Cruse: “We who are dark can see America in a way that white Americans can not.” To truly understand American capitalism—its strengths and weaknesses—it helped to be among the most exploited caste. But tragically, Black intellectuals had also failed in this mission. “It evidently never occurred to Negro revolutionaries,” Cruse wrote, “that there was no one in America who possessed the remotest potential for Americanizing Marxism but themselves.”

This critique of the left would have been considered heresy in the 1930s—indeed Calverton was written out of the Communist left—but by 1967 some were ready to hear it. Christopher Lasch wrote an extremely favorable review of the book, praising its nationalism. (At the time, Lasch was still a member in good standing of the left, since that review predated his shift to anticapitalist traditionalism). Lasch wrote: “American history seems to show that a group cannot achieve ‘integration’—that is, equality—without first developing institutions which express and create a sense of its own distinctiveness.” In supporting this claim, Lasch offered the example of the Irish and the Kennedys. Camelot was the result of a whole bunch of Irish immigrants who leveraged ethnic solidarity to achieve power in WASP America. Lasch even liked Cruse’s critique of Blacks for working alongside white leftists. “Cruse accuses integrationists of being taken in by the dominant mythology of American individualism and of failing to see the importance of collective action along ethnic lines, or—even worse—of mistakenly conceiving collective action in class terms which are irrelevant to the Negro’s situation in America.”

Cruse believed that ethnic or racial solidarity was a more effective way to achieve political power than class solidarity—because he believed ethnicity and race were more authentic, perhaps even more naturalif I dare use that now forbidden word. This led him to the controversial argument that the American Communist Party was mostly a vehicle for Jewish power. Black intellectuals and activists who worked within the Communist Party were thus unwittingly working for Jewish power, which was ultimately a barrier to Black power. Cruse wrote: “the great brainwashing of Negro radical intellectuals was not achieved by capitalism, or the capitalistic bourgeoisie, but by Jewish intellectuals in the American Communist Party.”

Cruse’s blunt analysis of Black-Jewish relations led to charges of anti-Semitism. Historian Mark Naison claims that, beyond the anti-Semitic fringes of Black nationalism, specialists don’t take that aspect of Cruse’s book very seriously anymore. It sounds too conspiratorial. To me, though, such analysis is merely the logical outgrowth of zero-sum identity politics, which is grounded in racial or ethnic nationalism. Any honest Zionist would make a similar claim in reverse. So, in concluding this essay, I’m not going to focus on the boring question of whether Cruse was an anti-Semite, but rather on a more interesting question: Did Cruse’s ethno-determinism distort his analysis of class solidarity in general and the Communist Party in particular?

Cruse’s blunt analysis of Black-Jewish relations led to charges of anti-Semitism. Historian Mark Naison claims that, beyond the anti-Semitic fringes of Black nationalism, specialists don’t take that aspect of Cruse’s book very seriously anymore. It sounds too conspiratorial. To me, though, such analysis is merely the logical outgrowth of zero-sum identity politics, which is grounded in racial or ethnic nationalism. Any honest Zionist would make a similar claim in reverse. So, in concluding this essay, I’m not going to focus on the boring question of whether Cruse was an anti-Semite, but rather on a more interesting question: Did Cruse’s ethno-determinism distort his analysis of class solidarity in general and the Communist Party in particular?

Short answer, yes. Now to the long answer.

I’m not about to flip Cruse’s script and argue that race and ethnicity are constructions but that class is something more elemental. Class is indeed a constructed identity that is based on social relations—much like race—and thus must be contextualized. E.P. Thompson’s Making of the English Working Class shows this dynamic to be true. Yet, saying something is constructed does not entail it has no power—quite the opposite!

Those who joined the Communist Party had many reasons for doing so, but the most common reason was class solidarity. As Vivian Gornick shows in her magisterial book, The Romance of American Communism, people who joined the party often did so either because they identified as working class and thought that it served their class interests, or because they wanted to demonstrate solidarity with working class folks. Cruse’s experience in the Communist Party might have led him to a different conclusion—an experience filtered through his identity as a Black man—but that does not make his conclusion historically accurate.

One telling sign that Cruse’s idea that the Communist Party was a vehicle for Jewish nationalism was wrong: he thought Karl Marx was the originator of this impulse. In fact, nothing could have been further from the truth. Marx was ethnically Jewish, so to speak—his father was Jewish before converting to Protestantism to secure his standing as a lawyer in a Prussian society that barred Jews from many professions—but he was an atheist through and through and thought religious belief was a barrier to organizing the working class.

Beyond being wrong about the history of race and the American left, I would also argue that Cruse was wrong about the politics of race in relation to the left. Class solidarity is a better political vehicle than racial or ethnic solidarity.

Race complicates the matter of class greatly—race and class should never be conceptualized in isolation from one another. I’ve learned my lessons from the growing historiography of racial capitalism. I’ve read my Du Bois, C.L.R. James, and Cedric Robinson. And yet. Class solidarity, constructed or not, has done more to threaten the ruling class than racial or ethnic solidarity. This is for good reason—the ruling class is just that, a class.

I recognize such a contention is far from settled. Especially since Ta-Nehisi Coates’s bleak essays about how white supremacy is trans-historically fused with American society—from Fitzhugh to Trump—are widely celebrated as works of genius.

To be fair to Cruse, most liberals in the late 1960s either ignored or rejected his arguments, mostly because Crisis dumped a bucket of cold water on celebratory accounts of the civil rights movement. Coates, on the other hand, seems to have tapped into the psyche of American liberalism unlike any writer in decades. Cruse’s vision of American race relations was pessimistic but he offered a way out in the form of racial nationalism. In contrast, Coates offers us crippling despair (and reparations, it should be noted). Weird as it sounds, Coates is tonic for liberal Americans who invested their hopes and dreams in Obama only to have them crushed by Trump. Cruse was never anyone’s tonic.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Professor Hartman, I appreciate greatly your informative discussion of Harold Cruise and his absolutely ruthless criticism of just about everything (and I think he’d have liked your title). I will ponder your discussion of Cruise & Coates as well.

But I do have a question. Very early on you say the Studies on the Left editors had problems with an article submitted by Cruise in 1962, because they had

“difficulty seeing the value of a social philosophy based on the ideas of Malcolm X.” Was Cruise following the ideas of Malcolm X in 1962? This is a genuine question. As far as I know, Cruise wasn’t influenced by Malcolm when Malcolm was still in the Nation of Islam, as he was in 1962. Later seems more likely. Do you mean that Cruise’s Black nationalism resembled that that Malcolm was soon to articulate? Or that Cruise was truly influenced, by 1962, by Malcolm’s ideas? Thank you for this terrific essay!