Haitian Writer Baron de Vastey and Black Atlantic Humanism: An Interview with Marlene L. Daut

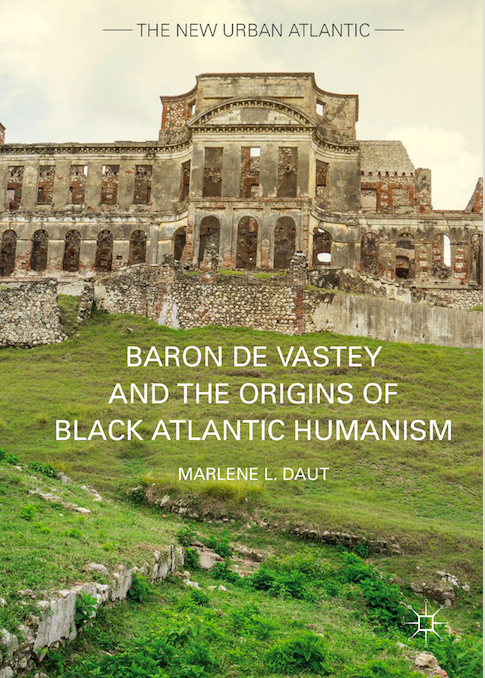

In today’s post, Julia Gaffield, Assistant Professor of History at Georgia State University, interviews Marlene L. Daut on her new book Baron de Vastey and the Origins of Black Atlantic Humanism, which was recently published by Palgrave Macmillan’s series in the New Urban Atlantic. Daut is Associate Professor of African Diaspora Studies in the Carter G. Woodson Institute and the Program in American Studies at the University of Virginia. Before joining the faculty of UVA, Daut was Associate Professor of English and Cultural Studies at Claremont Graduate University. She has been the recipient of fellowships from the National Humanities Center, the Ford Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). In addition to Baron de Vastey and the Origins of Black Atlantic Humanism, she is the author of Tropics of Haiti: Race and the Literary History of the Haitian Revolution in the Atlantic World, 1789-1865 (Liverpool University Press). Her articles have appeared in scholarly journals such as, Studies in Romanticism, L’esprit créatur, Small Axe, Nineteenth-Century Literature, Comparative Literature, South Atlantic Review, Research in African Literatures, and J19. She is also co-editor and co-creator of H-Net’s scholarly network, H-Haiti and curates Fictions of the Haitian Revolution and La Gazette Royale. She is currently working on an anthology of fictions of the Haitian Revolution published from about 1787-1900 (under contract with the University of Virginia Press); and an intellectual history of Haiti, spanning the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Follow her on Twitter @FictionsofHaiti.

Julia Gaffield: The Enlightenment is both central to and in conflict with the emergence of Black Atlantic humanism. What is Black Atlantic humanism? How does it inform our understanding of universalism?

Marlene Daut: In his writing, Baron de Vastey (1781-1820) highlights how Enlightenment-era thinkers attempted to categorize all manner of objects (plants, birds, rocks, flowers), which in turn led them to create hierarchies of humanity. The hierarchies created by natural historians like Comte de Buffon, Edward Long, and M.L.E. Moreau de Saint-Méry ended up being used to support slavery and justify racial prejudices. Instead of promoting universal liberty and equality among humankind, which many so-called philosophes had gestured towards as the goal of enlightenment, the Enlightenment writ large was responsible for the development of entire racial taxonomies that placed white Europeans at the top of humanity and Black Africans at the bottom.

The Black Atlantic humanists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, of which Baron de Vastey was a distinct and important part, contested this so-called Enlightenment by revealing it to be utterly devoid of the humanity in whose name it was developed and proclaimed. In this book, I return to some of the first writers of African descent who criticized the Enlightenment, as such. Those authors were people like Olaudah Equiano (1745-1797), Ottobah Cugoano (1757-1791), and Baron de Vastey. This movement of counter-Enlightenment is what I call Black Atlantic humanism precisely because of the tension involved in that formulation. Humanism has a bad name today because it is associated with the Enlightenment, which many scholars now acknowledge reflects the racisms of the early modern world, and because it suggests the primacy of human beings in the animal kingdom and in the environment, more broadly. But Black Atlantic humanists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries thought that the universalisms of the Enlightenment were good—liberty and equality for all human beings—but that the practices of slavery, colonialism, and prejudice were undermining them. That is to say, the metaphysics of Enlightenment universalisms, in theory, were absolutely central for “civilization” to someone like Baron de Vastey. But, he recognized the Enlightenment as a failure thus far because European society, consumed with racism, pride, greed, and a corruption of the soul, had deemed a large part of humankind unequal and therefore not subject to universalities.

Gaffield: Why is Baron de Vastey’s historical role marginalized in the twenty first century?

Daut: After the Haitian Revolution, many abolitionists from the Atlantic World grappled with the fact of Haitian independence. It was easy for writers of the early nineteenth-century to oppose early Haitian sovereignty on the grounds of the absolute violence that had been used to achieve it. Vastey was one of the first writers of color to say, well, hold on a minute: the Haitian Revolution was violent, yes, but that’s because the French colonists had committed “unheard of crimes that made nature shudder.” In his most important work, Le Système colonial dévoilé (1814), Vastey called out the already voluminous writings on the Haitian Revolution that decried the violence of the formerly enslaved while forgetting the inherent violence of slavery itself. It is telling that Vastey’s most damning exposé of the inhumanity of colonialism was never fully translated into English in his own era and has only recently been translated in our own. The catalog of abuses he records is in large part responsible for that, to my mind.

Vastey was a complex historical figure for other reasons, too. He was a phenotypically white writer with a French colonist, slave-owning father and a free woman of color as a mother. This son of an enslaver ended up being the principal secretary of Haiti’s King Henry Christophe I. I think there is still some uneasiness about the role of the state, even, or maybe especially, a Black state, in the Black radical tradition. If Vastey was a state actor, then was he truly a radical? This is not a question that my book seeks to answer. Instead, I think we should try to understand who Baron de Vastey was, as a man of his own era, and less who we would have wanted the person who wrote these amazing avant la lettre anti-slavery, anti-colonial, and pro-Black sovereignty texts to be in our own era.

Gaffield: Sovereignty is central to Vastey’s understanding of humanity; how does his articulation of universalism shape our understanding of freedom and abolition?

Gaffield: Sovereignty is central to Vastey’s understanding of humanity; how does his articulation of universalism shape our understanding of freedom and abolition?

Daut: There are two kinds of sovereignty evident in Vastey’s works—personal sovereignty and political sovereignty. For Vastey, both were fundamental to promoting racial justice, but only one had the capacity to do so from an institutional perspective; only political sovereignty could change the status of every enslaved person. In the US before 1865, political sovereignty was not really an option, even for the free people of color. Vastey’s writings highlight a difference between the form of sovereignty that would later become popular to narrate in the US African American slave narrative (autobiographies of fugitives of slavery like William Wells Brown, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, etc.), and the form of sovereignty demonstrated by Haiti’s founding political documents (the texts that abolished slavery in all of Haiti and established Haitian independence). Haitians were free and independent regardless of personal inclination, i.e. one person’s ability (even within a larger network like the Underground Railroad) to render themselves individually free. It is precisely because of the difference between personal and political sovereignty that Vastey believed the goal of abolition needed to be the creation of more political institutions in which Black people would play a central part.

Gaffield: The printing press is a central feature of freedom and sovereignty in Vastey’s writing and in the broader efforts of the Haitian state(s) for diplomatic recognition; how did Vastey weaponize language and print media?

Daut: Vastey was adamant that Europeans had used the printing press to support slavery and colonialism. But he recognized the invention of the press to be a very powerful technology that the enslaved and formerly enslaved could also use to support and maintain their own liberation. In the hands of the Haitian state, Vastey thought that the press would spread the ideals of the Haitian Revolution throughout the rest of the world. Those ideals were freedom from slavery, equality under the law, and the end of colonialism in the Americas. So much of the world had already read the founding documents of Haitian sovereignty—the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of 1805—and journalists from the US, England, France, Germany, Denmark, etc. followed very closely events in the Kingdom of Hayti. There are dozens of mentions in the early national US press of Vastey’s writings,and his pamphlets and history books were often used to support arguments for the formal recognition of Haitian sovereignty. Even after Vastey’s death, his words, like those of many Haitian authors and politicians, continued to circulate, and to be used in attempts to destroy the foundations of slavery.

Gaffield: You highlight the importance of the royal “we” in Vastey’s writing as a literary technique that allowed him to speak for the enslaved after “interrogating the ashes and tombs.” What methodology allowed him to do this?

Daut: It is striking that Vastey was writing a “history from below” in the early nineteenth century. For Vastey, death was not an obstacle to accessing the experience of slavery, hence the ashes and tombs that he claims he is awakening and interrogating. Vastey also wrote that he not only interviewed the victims of slavery themselves, but that he essentially interpellated their mutilated limbs and their scars, as remnants of the tortures that they had experienced, to produce a history of the enslaved of colonial Saint-Domingue from their own perspective, the first of its kind in the entire Atlantic World. He uses “we” to stress the collective nature of his writing and to stress the continuity of it. His work is crucial to understanding how we should talk about lived-memory. When Vastey published Le Système, Haiti had only been independent for 10 years. The memory of slavery was fresh and extremely vivid for those who had lived through it. Part of what Vastey is doing here is to say that just because slavery has ended in Haiti, it doesn’t mean that the formerly enslaved or their ancestors had forgotten what they suffered. How long would it take them to forget? Would our dead ancestors want us to forget? These are questions that Vastey was grappling with as he tried to write a history of slavery and then of Haiti that would oppose the dominant, colonial perspective surging through European writings about the events of the Haitian Revolution and about Haitian independence. I think today’s scholars are still struggling to fully realize and/or replicate the kind of methodology Vastey employed. Which is to say, how do we talk to the dead rather than solely about them?

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.