Haiti and the Atlantic World: An Interview with Julia Gaffield

This month, I interviewed Julia Gaffield about her new book, Haitian Connections in the Atlantic World: Recognition after Revolution (University of North Carolina Press, 2015), which received the 2016 Mary Alice and Philip Boucher Book Prize from the French Colonial Historical Society. Exploring the relationship between the Haitian state and the slaveholding societies of the Atlantic World, Gaffield analyzes how the leaders of newly-independent Haiti established relationships with the international community after 1804. Drawing on archival sources from the Caribbean, Europe, and the United States, she reveals the strategies that Haitian leaders employed in their dealings with foreign powers and their far-reaching efforts to secure legitimacy and sovereignty.

Dr. Julia Gaffield is Assistant Professor of History at Georgia State University. After completing her undergraduate studies at the University of Toronto, she earned an M.A. from York University and a Ph.D. from Duke University. She is the editor of The Haitian Declaration of Independence: Creation, Context, and Legacy (The University of Virginia Press, 2016) and has published articles in Slavery and Abolition, William and Mary Quarterly, Riveneuve Continents, and the Journal of Social History. You can follow her on Twitter @JuliaGaffield.

Reena Goldthree (RG): Haitian Connections in the Atlantic World chronicles how Haitian officials constructed diplomatic, commercial, and military ties with foreign governments and merchants in the early nineteenth century. Your book joins a remarkably rich body of scholarship on the Haitian Revolution and on Haiti’s place in the Atlantic World. When did you first become interested in Haitian history? What books on the Haitian Revolution were most important to you as you embarked on this project?

Reena Goldthree (RG): Haitian Connections in the Atlantic World chronicles how Haitian officials constructed diplomatic, commercial, and military ties with foreign governments and merchants in the early nineteenth century. Your book joins a remarkably rich body of scholarship on the Haitian Revolution and on Haiti’s place in the Atlantic World. When did you first become interested in Haitian history? What books on the Haitian Revolution were most important to you as you embarked on this project?

Julia Gaffield (JG): A class at the University of Toronto taught by Melanie Newton first sparked my interest in Haiti. The course presented a history that I’d never heard about and that until pretty recently wasn’t taught in high schools or even in undergraduate classes. That’s changing now, but over a decade ago that wasn’t the case. The class occurred at a time—during the 2003-04 academic year—when Haiti was in the international news because of the ousting of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. So, I was simultaneously learning about Haiti’s history and learning about contemporary politics. This was a whole new world that I hadn’t learned about before and I just wanted to know more. The first book that I read about the Haitian Revolution was The Black Jacobins by C.L.R. James and then also Carolyn Fick’s book, The Making of Haiti.

2004 was also the 200th anniversary of Haiti’s independence, so there was a lot of scholarly activity that year. It was the year that Laurent Dubois’ Avengers of the New World came out, followed shortly thereafter by John Garrigus’ Before Haiti. So it was a confluence of classroom experiences, contemporary politics, and then a burst of activity in the academic community that led me to study Haiti.

RG: Following Haiti’s Declaration of Independence in 1804, the major powers of the Atlantic World—including France, Britain, Spain, Denmark, the Netherlands, and the United States–withheld diplomatic recognition. Furthermore, France hoped to isolate Haiti from the international community. How did French agents attempt to subvert the new Haitian state and how did Haitian leaders respond?

JG: The French undertook a multi-pronged attack on Haiti’s legitimacy. This attack took the form of legal arguments, of moral arguments—which played into fear and racism—and also of economic arguments. In the legal realm, the Law of Nations really played a central role both in France’s attacks against Haitian independence and in Haiti’s defense of their own independence. In terms of the moral argument, France suggested that it was the duty of European white empires to band together. In this regard, they played on the fears of other imperial and colonial leaders who thought that the revolution in Haiti might spread elsewhere. Finally, the economic attacks arose from the fact that France had just lost the most profitable colony in the Atlantic World. The French warned other European powers that this could be their fate as well if Haiti was not stopped.

On the flip side, the Haitian state invoked the Law of Nations to argue that they had the right to declare independence. They also made an economic argument and encouraged other nations to come trade with them. The state was still focused on the export economy, so there was economic opportunity to be had for potential trading partners in Europe and the United States. And then, Haitian leaders spent a lot of time reassuring the international community that they would not export their revolution and that the revolution would stay within the borders of the island. Ada Ferrer has some great work on the flexibility and nuance of the Haitian government’s promises. Ultimately, they maintained a balancing act between reassuring the international community and providing opportunities for freedom and citizenship to the non-white community of the Atlantic World.

RG: In the book, you explicitly challenge the “isolation thesis,” the argument that independent Haiti was isolated by the major powers of the Atlantic World during decades immediately following 1804. Instead, you suggest that the Haitian state enjoyed forms of “layered recognition” during the long period of diplomatic non-recognition. Tell us more about that.

JG: If sovereignty is understood as an all or nothing game, then we lose the nuance of the historical moment in which Haiti became independent. Historians of slavery and emancipation have introduced the idea that there are degrees of freedom. Freedom was not and is not all or nothing and neither is sovereignty. If you think about sovereignty as a spectrum rather than as a yes or no answer, then there were all these ways that Haiti was recognized and was therefore not isolated. But the isolationist thesis covers up all of these different layers by assuming that diplomatic non-recognition tells us the whole story about Haiti’s place in the Atlantic World. What I found was that foreign governments and merchants were fully willing to engage economically with Haiti, which then led to forms of implicit or de facto recognition. This implicit recognition was often hashed out in Admiralty courts, but it also had some implications for popular understandings of Haiti’s status and whether it was independent or not. So it’s not only layers of recognition, but the relationship between those layers was not very well defined or clear cut.

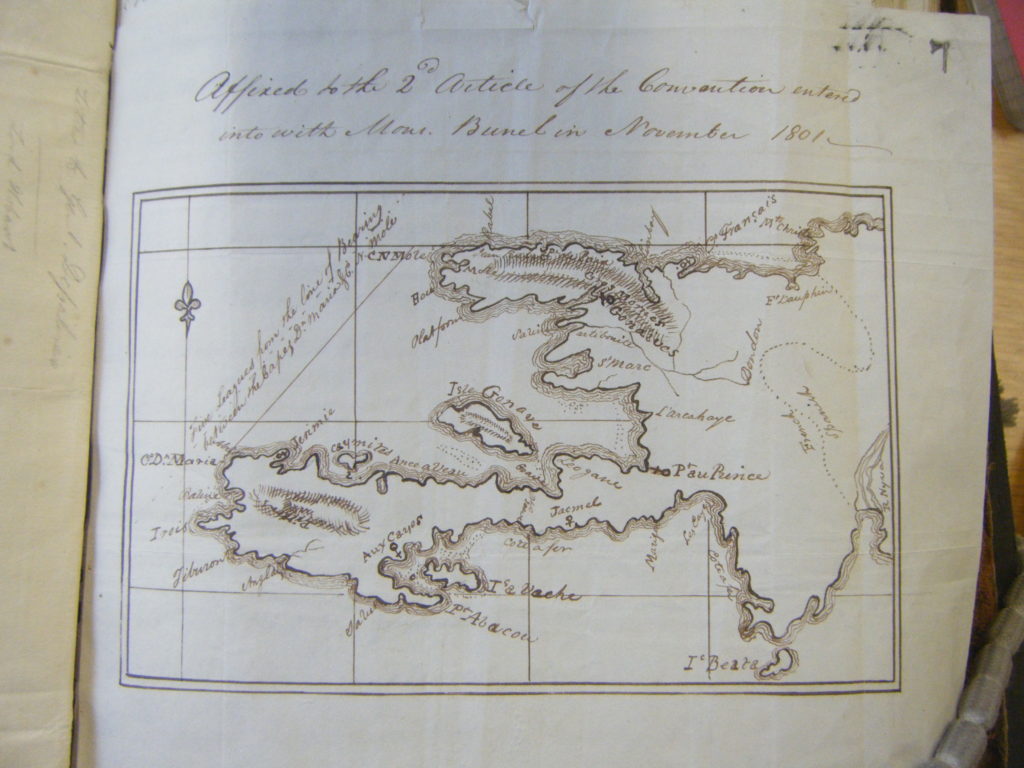

RG: Between 1803 and 1806, Jean-Jacques Dessalines attempted to secure a trade agreement with British officials in Jamaica. During this period, you argue that the “British engaged in an intricate dance of containment, isolation and engagement with Saint Domingue/Haiti in an effort to reap the greatest benefit without further disruption to colonialism and slavery.” How do you make sense of Britain’s stance vis-à-vis Haiti?

JG: The most important contextual feature of this time period was that it was a time of war, which meant that the British had multiple goals in mind when negotiating with Haitian leaders. Rather than complying with French calls for European or white imperial unity, the British saw Haiti as an opportunity both in terms of war strategy and in terms of commerce. Of course, engaging with Haiti involved certain risks and the British were well aware of that. In particular, they wanted reassurance that the plantation economy in Jamaica would not collapse because of a similar slave revolt or revolution. As a result, there was an aspect of containment that the British focused on in their relationship with Haiti.

In order to contain the revolution, the British tried to prevent Haitians from leaving Haiti. They wanted a barrier around the island and they also withheld diplomatic recognition. However, the isolation was only in one direction. They allowed British merchant and admiralty ships go to Haiti, but they weren’t willing to let Haitian ships leave. They were ultimately willing to engage economically, but they wanted to control the relationship. France’s huge economic loss in Haiti was to their benefit not only because France no longer had this income, but also because it allowed Britain to establish an informal commercial empire in Haiti without the responsibility of actual governance. Ultimately, the British had all these different priorities, which I think surprises people who are thinking about this from a twentieth-first century perspective. We assume that their only concerns were the maintenance of slavery and the centrality of racism–which were very important—but, they also had competing factors such as the ongoing war with France.

Haitian leaders were well aware of Britain’s competing objectives and interacted with British officials and commercial agents very strategically. The book calls attention to the diplomatic savvy of Haitian leaders in playing these imperial powers off of each other and knowing that there were competing interests that they could take advantage of and because of this they resisted conceding to British demands.

RG: Your book demonstrates that Haitian leaders were able to cultivate important economic relationships with foreign powers during the early years of independence, despite the lack of diplomatic recognition. However, in the conclusion, you briefly discuss how Haiti’s fraught diplomatic status affected the new nation. How did the struggle to secure diplomatic recognition affect internal affairs in early independent Haiti?

JG: One point that I discuss in the book, which I think is key but really difficult to find in the sources, is the issue of dignity. It was only after my book was published that I found the perfect way to articulate the importance of dignity to Haitian officials. In The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon writes, “The African peoples quickly realized that dignity and sovereignty were exact equivalents.” The importance of dignity is really hard to trace in the archival record, but the lack of diplomatic recognition denied the Haitian state dignity and legitimacy in both international and internal relationships.

Another example of the internal implications can be seen during the period of civil war; had foreign governments recognized either Alexandre Pétion’s or Henry Christophe’s government, it would have given them the power to actually rule the entire country. In the longer term, and I think there’s still a lot of research to be done on this, formal recognition might have affected the relationship between the state and the nation, as Michel-Rolph Trouillot has described it. Had the Haitian state enjoyed international legitimacy, I think that relationship might have looked different in the nineteenth century.

Reena Goldthree is an Assistant Professor of African and African American Studies at Dartmouth College. Her current book project is titled Democracy Shall be no Empty Romance: War and the Politics of Empire in the Greater Caribbean.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thank you for publishing this article on Haiti. I want people to begin to understand us and our dignity and our history. We went our own way and decided our own freedom and were punished mercilessly for it. So be it. Through the diaspora, we are incredibly alive and we are not going anywhere.

Thank you for this article. I am of Haitian descent and my parents always wanted us to be proud of our history and now as a mother, I am teaching my sons about beautiful Haiti.