Gloria Richardson and the Struggle for Black Liberation

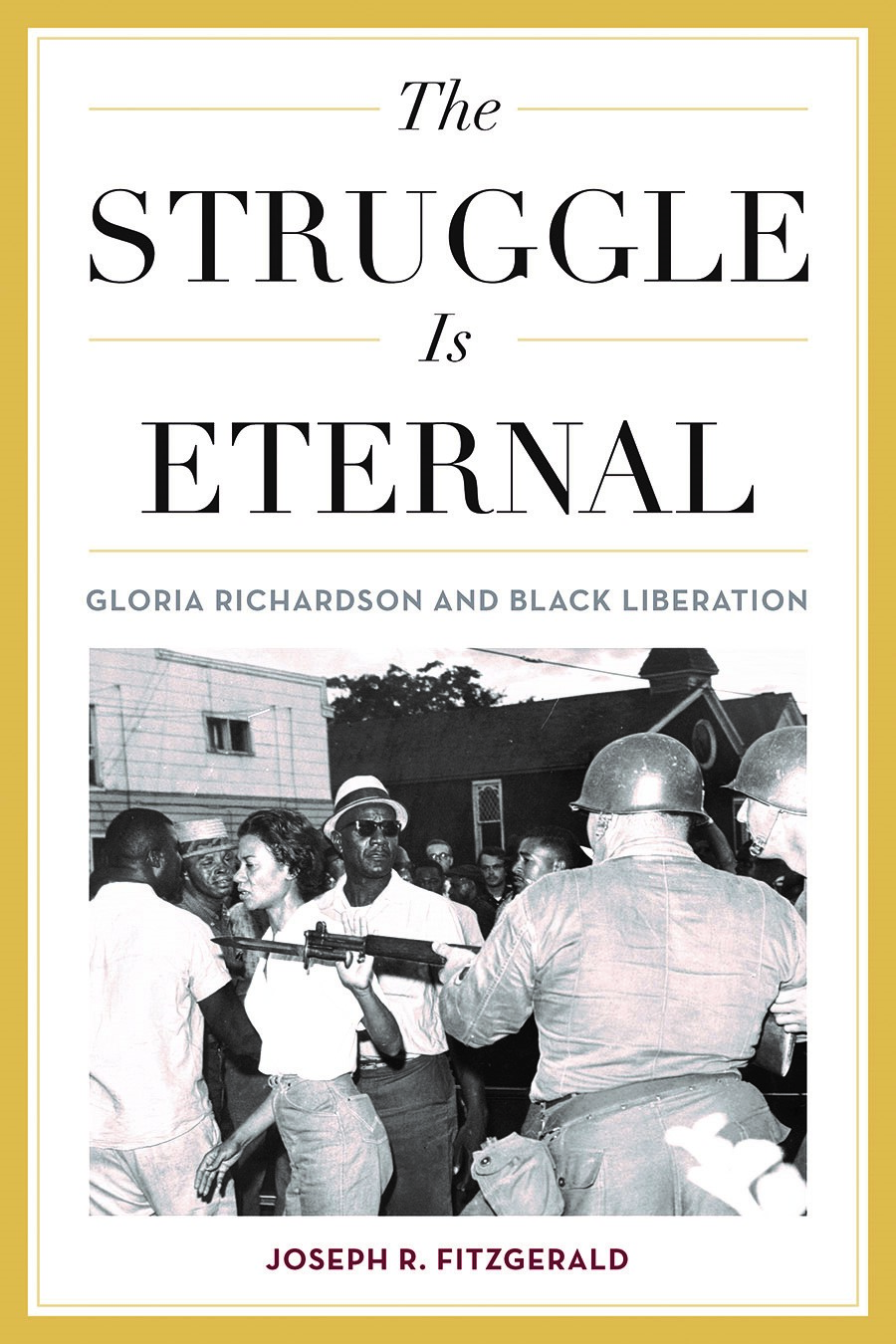

This is an excerpt from Joseph R. Fitzgerald’s The Struggle is Eternal: Gloria Richardson and Black Liberation, scheduled to be published by the University Press of Kentucky in November 2018. The book explores ‘the largely forgotten but deeply significant life of this central figure and her determination to improve the lives of black people.’ This excerpt has been reprinted with permission.

When Gloria Richardson was asked how she would like to be remembered, she replied: “I guess I would like for them to say I was true to my belief in black people as a race.” Her answer reveals a deep commitment to the struggle for black liberation, grounded in an understanding that since colonial times, millions of black people have been forced to sacrifice life and limb in the building and enriching of this nation. Because of this, white America should dismantle its racial hierarchy. Richardson believes so strongly in black people’s entitlement to real and meaningful freedom that she never thought twice about risking her life during the civil rights movement. Still, she knew that bravery alone would not be enough to bring about societal change, so she used her leadership abilities and sociological training to further the cause of human rights, and in doing so, she carried on her family’s tradition of race service. Richardson’s activist work was so important to her that, when asked if she could live at any time in American history, when that would be, she chose the mid-1960s because “there was a lot of ferment and ideas and struggles to finish freeing black people in the progression from slavery . . . a lot of ground was covered at that time.”

The civil rights movement also served as the vehicle by which Richardson reached self-actualization. Donna Richardson recalled her mother’s life being so restricted by racism that “she was looking for something to stimulate her,” and the Cambridge movement was what got Gloria Richardson going each day. The movement itself, Donna added, “kind of infused life into our house,” and it had a noticeable effect on her mother. “I could see a change in her” as she became “passionate” about the movement and had something to “focus” her energy on. Gloria Richardson’s relationship to the movement was essentially the same as that of fellow SNCC member Casey Hayden: “[The movement] was everything: home and family, food and work, love and a reason to live.”

Not surprisingly, if given the chance to do it all over again, Richardson would not do anything differently. Her confidence comes from a mixture of things. For one, Richardson’s parents and her extended family groomed her for race service, and perhaps more important, they encouraged her to be her own person and to stand up for herself. That socialization was reinforced at Howard University by professors who challenged Richardson to use her critical thinking and her education to advance her race. Her understanding that “nobody has all the answers” was developed during her years at Howard and validated during the Cambridge movement, when she and her fellow grass- roots activists engaged in rigorous dialogue and debate to identify their own needs and problems and find creative solutions. If readers of this biography gain anything from Richardson’s story, she hopes it is the lesson that when people with a shared goal join together, they can “fight city hall” and win, and that can lead to a radically transformed society. In addition, she wants people to remember that voting is not a panacea for black people’s problems; rather, it is “one egg in a basket” of tactics that can be used to bring about some changes.

After living in relative obscurity since the mid-1960s, Richardson has been receiving recognition for her human rights activism over the last ten years. She has been awarded honorary doctorates and numerous public service awards and citations. A Maryland bar association and a Cambridge street have been named after her, and she is depicted in a mural at the entrance to Cambridge; she is also included in materials promoting Maryland history. Over the last handful of years, Richardson once again entered the nation’s consciousness when commemorations of the March on Washington’s fiftieth anniversary highlighted her experiences at the original event in 1963. This biography continues her reintroduction to the public and reveals the all- important philosophical underpinnings of her activism.

From a scholarship standpoint, Richardson’s story both expands and challenges narratives about the civil rights and Black Power waves of the black liberation movement. It broadens our view of political leadership and intellectualism beyond the male-centric scholarly interpretations of 1960s black protest. Richardson’s personality traits were critical to her success as a leader of the Cambridge movement and ACT. She stayed true to her belief that black people’s rights were nonnegotiable and she showed herself to be strong-willed, unassuming, polite, and open to other people’s ideas and input. Just as important was her refusal to leverage her political and social power for personal gain. This amalgam of traits and ethics fostered a respectful environment in which Cambridge’s ground troops, so to speak, entered the battle for freedom each day knowing that Richardson was as committed to them as they were to her. The histories of the Cambridge movement and Gloria Richardson’s leadership of it will require scholars to expand their understanding of where Black Power began and who played a role in its creation. Using the findings from the community survey Richardson designed, the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee implemented a social justice campaign that focused on access to jobs, decent housing, and health care—an agenda Black Power advocates would soon adopt throughout the nation. As such, Cambridge was the soil where Richardson planted a seed of Black Power, and she nurtured it through strong leadership and a radical vision that understood the nexus between race and class oppression. She then stimulated Black Power’s growth when she cofounded ACT, which spread the Cambridge movement’s successes to northern cities. Adding to Richardson’s significance as a progenitor of Black Power was her unqualified support of black people’s right to use the tactic of armed self-defense and the high value she placed on black American culture.

Because this biography foregrounds Richardson’s social, economic, and political philosophies and why she acted on them, it also challenges a commonly held but nevertheless false view that black women are primarily doers rather than thinkers. The foundation of her philosophies was secular human- ism, a belief system that affirms all human life and promotes a nonhierarchical social system based on fairness and equity. Specific examples of Richardson’s philosophies can be found in her civil rights goals and the strategies and tactics she used to achieve them, such as creative chaos carried out through obfuscation, silence, economic boycotts, threats of demonstrations, and a boycott of the polls. Richardson was instrumental in bringing Cambridge’s white power structure to heel and forcing it to implement tangible programs to improve black people’s lives. For this, and for her role in helping to expand the black liberation movement beyond the issues of open accommodations and voting rights, Richardson has earned a place in the pantheon of radical black freedom fighters and intellectuals, a body that includes such notable figures as David Walker, Harriet Tubman, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and W. E. B. Du Bois.

Although she has never been optimistic about America’s ability to honestly confront its history of systemic racism, Richardson has seen black people’s lives improve since the 1960s, and she is hopeful that progress can continue. In the early 1960s she described Cambridge as a microcosm of race in America, and it continues to be that. To Richardson’s surprise and satisfaction, the city has moved forward socially and politically since the tumultuous years of the 1960s. The election and reelections of Mayor Victoria Jackson-Stanley are evidence of that progress. Her initial win in 2008 marked two firsts for Cambridge: she was the first black person and the first woman elected mayor of the city. A couple of black residents have established a new community organization, Eastern Shore Network for Change, whose “mission is to raise awareness of issues in Dorchester County and to creatively work with the community to inform, educate, and foster change which leads to social and economic empowerment.” In the summer of 2017 the group held “Reflections on Pine,” a series of events highlighting the importance of the Cambridge movement, as well the need for residents citywide to come together to work on racial healing and improving the quality of life for all.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.