George Jackson: Dragon Philosopher and Revolutionary Abolitionist

International Revolutionary Struggle

“People who come out of prison can build up a country. Misfortune is a test of people’s fidelity. . . . When the prison doors are opened, the real dragon will fly out.” — Ho Chi Minh

Inspired by Vietnamese nationalist Ho Chi Minh, who met Harlem Garveyites, Korean nationalists and Chinese communists, George Jackson (1941- 1971) found within the California prison yards and cells—he was entombed in solitary confinement for seven of his ten years of incarceration—mentors for revolutionary struggle. The Vietnamese independence leader and guerilla fighter who helped to create the Viet Cong, Ho Chi Minh, describes how a prisoner becomes a dragon. George Jackson, referencing South American revolutionary who fought for Cuba, Che Guevara, describes how a Black prisoner can engage in an alchemy that turns a slave into a dragon.

As did Ho Chi Minh, George Jackson initially sought to play by the rules of diplomacy, negotiation and compromise, linking Third World liberationists as international phenomena. George Jackson politicized himself into being a hyper-intellectual. Reading avidly and widely to comprehend and dissect violence, Jackson sought a fulcrum from the site of prison to leverage an omnipotent oppressor that wielded more violence than the colonized, enslaved, and imprisoned could ever amass against their rulers and masters and guards. Jackson was in solitary confinement when the 1968 Tet Offensive by the Viet Cong rattled the US imperial military and put it on the road to defeat. The US war against Vietnam led to 2-3 million Vietnamese and 55 thousand American deaths.

According to former Harlem Black Panther Party (BPP) member K. Kim Holder, Jackson was an embodiment of what the Third World liberationists sought: how from the space of captivity to forge a liberation movement; hence, George Jackson embraced his role as dragon philosopher before he became a Black panther. The former would prove more controversial than the latter. For Holder, Jackson’s ability to theorize against violent racist repression behind prison walls prepared panthers who would be captured, tortured and interred for years if not decades. Jackson “laid it down” for the Attica rebellion as well as political prisoners who broke out of prison in defiance of joint FBI/CIA Cointelpro and police task forces seeking to destroy freedom movements at home and abroad.1

Political Leadership from the Captives

“As a slave, the social phenomenon that engages my whole consciousness is, of course, revolution. Revolution should be love inspired.” — George Jackson, Blood in My Eye

On August 21, 2018, imprisoned activists began a national strike in seventeen states for human rights and to end prison violence and penal slavery. From the anniversary of George Jackson’s August 21, 1971, death at the hands of California prison guards, and Nat Turner’s slave rebellion in 1831, to the September 9, 1971, eruption of the Attica prison revolt in New York, the incarcerated and enslaved seek the support of those on the outside for their strike against torture and dehumanization. Some invoke the name of George Jackson; others do not. As one of the architects of the Prisoners’ Rights Movement, Jackson’s presence is imprinted on abolitionism.

The prison is an extension and expression of the revolutionary underground, slave quarters, convict labor camps, torture sites, family disintegration, and the revolutionary underground. Building bridges of solidarity between prisoners and those of good will in the “free world” spans the decades and dungeons within prisons which created George Jackson as man and myth. As the “free world” shrinks to take on the characteristics of repressive policing, detention and disappearance, the legacy of George Jackson and revolutionary abolitionism and dragon philosophy will come under greater scrutiny.

George Jackson learned to be a revolutionary from other politicized prisoners. He was close to twenty-year old W. L. Nolen; they were in prison together in 1966 when they co-founded the Black Guerilla Family (BGF) as a political entity based on anti-racist class analysis and struggle. Both men had youths marked by crime, violence, and rebellion against prison authority. Both received indeterminate sentences for robberies. When both were moved to Soledad Prison, Nolen initiated a class action law suit on human rights violations: 1969 W. L. Nolen, et. al. v. Cletus Fitzharris. Nolen charged prison superintendent Cletus J. Fitzharris and prison guards with knowingly exacerbating “existing social and racial conflicts” through “direct harassment and in ways not actionable in court” including repressive prison tactics of filing false disciplinary reports and leaving Black inmates’ cells unlocked for racist, Aryan assaults; and “placing fecal matter or broken glass in the food served to New Afrikans.” Nolen feared for his life as a plaintiff. Four months after he filed his petition, he and another Black prisoner who had signed it were dead.

On January 13, 1970, the prison released Black prisoners and Aryan brotherhood prisoners into the recreational yard closed two years prior after the Aryan brotherhood beat two young Black prisoners to death. Surveying the racial fight from the guard tower—critics argue prison authorities staged it—former military marksman O. G. Miller, a white prison guard, without a warning, shot fired three times and killed three Black men: Cleveland Edwards, Alvin Miller, and W. L. Nolen (one white prisoner was wounded). Min Sun Yee’s 1973 Ramparts article, “Death on the Yard,” (the same issue covers the assassination of Amílcar Cabral), counts the murders that followed O. G. Miller’s triple homicide as 40, with no CDC guards or staff ever charged for the shooting deaths.2 Black prisoners made what they thought were reasonable and legal requests: the arrest of Miller the shooter and a grand jury investigation. The Monterey County DA waited three days before announcing his ruling which Black prisoners watched on television: the deaths of Black men doing civil rights reform inside prison were ruled “probable justifiable homicide by a public officer in the performance of his duty.” One hour later, a white guard, John Mills, was thrown over an upper tier in the Y-wing; he died in the prison hospital without regaining consciousness. Without evidence, the prison authorities charged George Jackson, Fleeta Drumgo, and John Cutchette with the death of Mills. The three became the “Soledad Brothers.”

On January 13, 1970, the prison released Black prisoners and Aryan brotherhood prisoners into the recreational yard closed two years prior after the Aryan brotherhood beat two young Black prisoners to death. Surveying the racial fight from the guard tower—critics argue prison authorities staged it—former military marksman O. G. Miller, a white prison guard, without a warning, shot fired three times and killed three Black men: Cleveland Edwards, Alvin Miller, and W. L. Nolen (one white prisoner was wounded). Min Sun Yee’s 1973 Ramparts article, “Death on the Yard,” (the same issue covers the assassination of Amílcar Cabral), counts the murders that followed O. G. Miller’s triple homicide as 40, with no CDC guards or staff ever charged for the shooting deaths.2 Black prisoners made what they thought were reasonable and legal requests: the arrest of Miller the shooter and a grand jury investigation. The Monterey County DA waited three days before announcing his ruling which Black prisoners watched on television: the deaths of Black men doing civil rights reform inside prison were ruled “probable justifiable homicide by a public officer in the performance of his duty.” One hour later, a white guard, John Mills, was thrown over an upper tier in the Y-wing; he died in the prison hospital without regaining consciousness. Without evidence, the prison authorities charged George Jackson, Fleeta Drumgo, and John Cutchette with the death of Mills. The three became the “Soledad Brothers.”

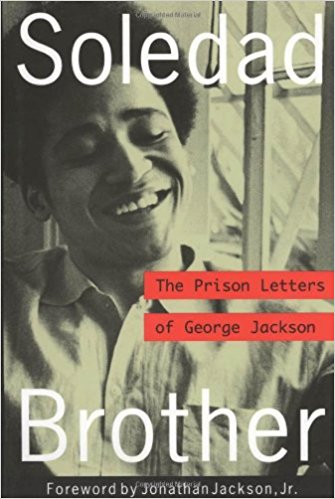

Led by George Jackson, the Soledad Brothers Defense Committee included Faye Stender, Georgia Jackson, and Angela Davis. In their own distinct ways, the three women, respectively George’s lawyer-lover; mother, and partner would memorialize Jackson and redefine prison abolitionism. Faye Stender defended him in court; helping to form the Soledad Brother Defense Committee which Angela Davis joined. Stender introduced Jackson to Bantam editor Gregory Armstrong who would publish Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson; and Jean Genet who wrote the foreword to Soledad Brother. Stender and Armstrong fought censors to ensure the book became a best seller; yet, both edited Jackson’s letters to make him seem more reasonable and less violent; more of a reformer than a dragon philosopher. In his February 13, 1970, Soledad Brother letter to Stender, Jackson allows for no adjustment to prison life: “Of the ten years I have done. . . which part of the jail I’m in doesn’t matter.”

Tragedy befell all three women who loved George Jackson. Each contributed a significant part of her life so that his suffering and murder would have meaning. Angela Davis was forced underground, imprisoned and survived incarceration as a political prisoner. Faye Stender was shot and crippled in 1979 by an alleged BGF member (the organization ceased being political after Jackson’s 1971 assassination), who accused her of betraying Jackson; Stender committed suicide in 1980. Georgia Bea Jackson buried her youngest son, Jonathan, in 1970, and her oldest son, George, the following August.

Proper Burials

“I come here to bury Caesar, not to praise him.” —Atony, William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar.

George Jackson insisted to Angela Davis that he only trusted his younger brother, Jonathan, to serve as her bodyguard given the multiple death threats she received after asserting her right to teach as a communist and anti-racist activist. When Jonathan brought Davis’s guns to the Marin County Courthouse on August 7, 1970, he took hostages to exchange for the freedom of the Soledad Brothers, and the life of his brother George. Prison guards and the district attorney killed Jonathan, the two Black prisoners William Christmas and James McClain who assisted him, and Judge Harold Haley. Guards fired into the van that Jonathan Jackson drove with the hostages and liberated prisoners; grabbing one of the guns, the DA began shooting inside the van (hit by gun fire from guards he was partially paralyzed for life). George dedicated Soledad Brother to Jonathan, giving him the honorific title of “Man-Child”:

Tall, evil, graceful, bright eyed, black man-child—Jonathan Peter Jackson—who died on August 7, 1970, courage in one hand, assault rifle in the other; my brother, comrade, friend,—the true revolutionary, the black communist guerrilla in the highest state of development, he died on the trigger, scourge of the unrighteous, soldier of the people; to this terrible child and his wonderful mother Georgia Bea, to Angela Y. Davis, my tender experience, I dedicate this collection of letters; to the destruction of their enemies, I dedicate my life.

The day after George Jackson died, his distraught father Lester Jackson shared on Oakland television that his eldest son confided to him that prison guards had starved and denied George clean drinking water for three days. Mr. Jackson’s grief-stricken interview also informed the public that George told Jonathan Jackson in late July 1970 that guards had promised to kill George on August 10. On August 7, the teen executed the risky raid on the Marin Courthouse. At the cost of his own life, he bought his brother an extra year. During that year, Jackson wrote the insurrectionary text heavily influenced by Jonathan, Blood in My Eye, which Toni Morrison edited for Random House for posthumous publication.

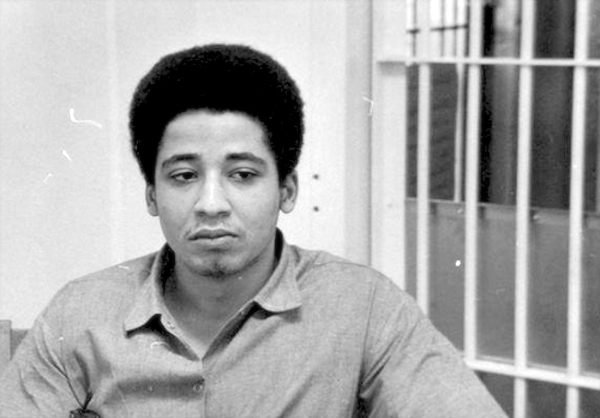

One might argue that Jackson could have survived if he waited out his sentence, kept his head down, compromised. Yet, George Jackson understood himself to be a marked man. He tried the legal approach and was rejected as a political threat. Police sought his neutralization. He was less the “Black messiah” that J. Edgar Hoover worked to eradicate from reform movements and more the Black dragon seeking an army to undo a repressive government. Eulogized in print, Jackson’s photo and reporting of his funeral attended by 8000, were the cover of the August 28, 1971, The Black Panther newspaper. Ja Rule, Archie Schepp, and Bob Dylan later memorialized Jackson in song.

Other narratives condemned George Jackson as directly or indirectly responsible for his own death and the deaths of three prison guards, and two trustees at San Quentin (surviving Soledad Brothers were acquitted at trial of killing the Soledad Prison guard). To ensure that a portrait of a homicidal criminal did not cover the theorist and abolitionist, in the documentary Day of the Gun, Angela Davis asserts that the “true horror” of August 21, 1971, is obscured by contradictory statements from prison authorities and survivors; for Davis, George Jackson “was a human being . . . . [with] joy in his heart”; as well as a symbol of Black oppression “who we absolutely had to save.”

Saving not the man but the meanings of revolutionary struggle suggests that George Jackson requires more analysis because of his proximity to a violence that has continued to grow in his absence. If prison and fascism are extensions of democracy’s rootedness in racial capital, then what is the meaning of his claim in the uncensored Blood in My Eye: “I can only be executed once. No matter what I do they will always explain me away….So I rage on aggressive and free.” For Jackson, dragon philosophers die first in body and later in reputation. Weeks after he was killed, Angela Davis from her prison cell wrote “Reflections on the Black Woman’s Role in the Community of Slaves,” published in The Black Scholar in December 1971, paying homage to slave insurrection and the feminization of her beloved:

I would like to dedicate these reflections to one of the most admirable black leaders to emerge from the ranks of our liberation movement—to George Jackson, whom I loved and respected in every way. As I came to know and love him, I saw him developing an acute sensitivity to the real problems facing black women and thus refining his ability to distinguish these from their mythical transpositions.

Dedicated to (un)gendered caretakers nurturing and protecting communities, memorials reveal that captive maternals came not to resurrect but to properly bury George Jackson; and to witness and testify to the inevitability of dragons emerging from dungeons.

Thanks for this timely article on George Jackson. After reading this, I am re-reading “who Killed George Jackson: Fantasies, Paranoia and the Revolution” by Jo Durden-Smith.