From Dissertation to Book: An Interview with Jill Petty

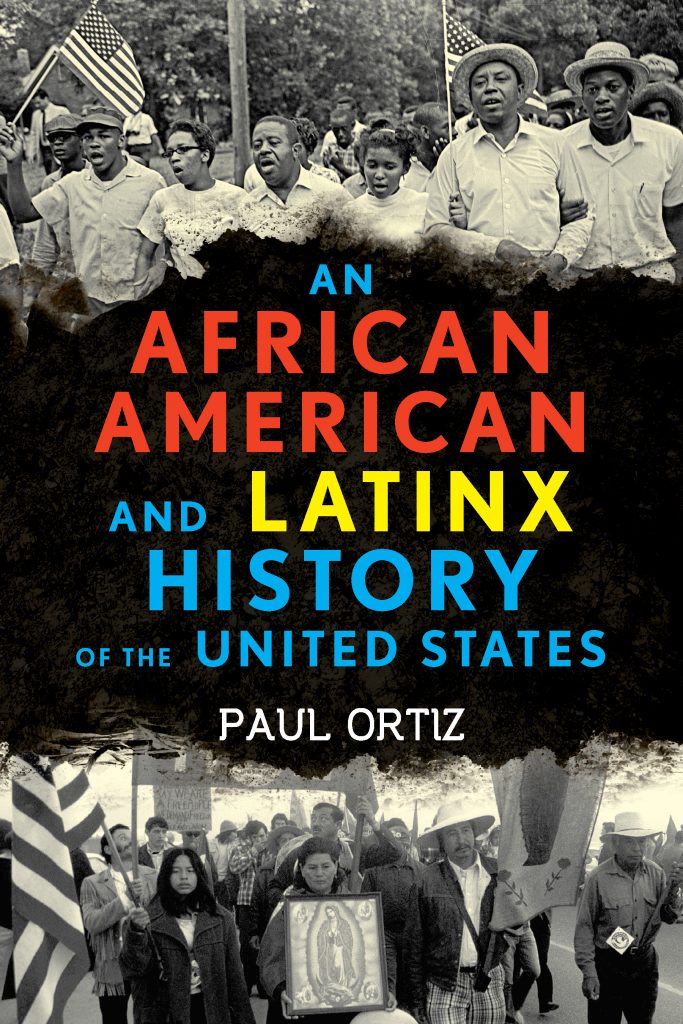

This month I interviewed Jill Petty about best practices for revising dissertations for publication, book proposals, and the differences between academic and trade publishing. Petty joined Northwestern University Press as Acquisitions Editor in March 2017. In the 2000s, she served as an editor-publisher for the nonprofit publishing collective South End Press, where she worked with Noam Chomsky, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, bell hooks, INCITE: Women, Gender Non-Conforming and Transpeople of Color Against Violence, Arundhati Roy, and other activist-authors. Before joining NUP, Jill was Chicago-based Senior Editor for Beacon Press, where she worked with a number of authors, including Bill Ayers, Charlene Carruthers, Karen Lewis, Andrea Ritchie, and Paul Ortiz. Jill has also done communications work for organizations advocating social change, including Equal Justice Initiative, the Alabama-based legal nonprofit led by Bryan Stevenson. She is a member of the Prison + Neighborhood Arts Project teaching collective, an abolitionist arts and humanities project at Stateville Maximum Security Prison, near Chicago. She also facilitates writing retreats for faculty at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Jill earned her BA in English from Grinnell College and her MA in English from Duke University. Follow her on Twitter @OneRedPencil.

Keisha N. Blain: What do you think is the most important piece of advice for prospective new authors, especially junior scholars who want to publish a book based on a dissertation?

Jill Petty: Two suggestions! Before you rework your dissertation, let it get cold. If possible, wait at least six months before picking up the finished dissertation to revise it. Allowing some breathing room into the process will be helpful. During this time, you can identify and recruit a support network will read your writing and help you transform it. In addition to peers, you might ask a committee member to recommend an outside reader—someone who is more removed from you and your work than they are, but who is trustworthy and knows the conversations your book should engage.

It may also be useful to enlist a reader who is four to five years out from earning their doctorate—perhaps someone who graduated your program—to provide additional perspectives. And it would be ideal to include a reader outside of your discipline in your reading network. But the important thing is to seek input from others. You’ll build up comfort with hearing constructive criticism—an asset for the publishing process—and your manuscript will improve.

As you transform your dissertation into a book, and prepare to shop it to publishers, this kind of reflection and feedback should prompt you to make some strategic changes. For example, as you revise, what information should you keep from your dissertation, and what should you jettison? Do you need to include additional (or different) examples? What kind of restructuring do you need to do across the manuscript? Does your language need to be less “jargony” or theoretical? (If you’re hoping to sign with a trade publisher, the answer is probably “yes.”) Do you need to include additional graphics—such as photos, timetables, maps, or charts—to make your book more reader-friendly and compelling? Are you pleased with your introduction and your conclusion? (Busy people often scan these sections first to determine if they will adopt your book for a class or if they will buy it to read.)

My other suggestion to new authors is to make a concerted effort to be open and flexible as you revise. One successful and productive professor friend shares that it helps her to think about long-term writing assignments as sewing projects. Your dissertation, for example, may provide the raw material for your book, but you may have to rip out the seams to create something new, something that “hangs better.” You may need to add zippers, or fetch more cloth and thread. So cultivate openness. Think creatively. Be resourceful, and have your scissors at the ready!

Blain: Most junior scholars, especially in the field of History, publish their first books with an academic press (and depending on one’s institutional requirements, there is little flexibility concerning this decision). However, some authors decide to publish their first books with a trade press. From your vantage point, what are some of the advantages and disadvantages of publishing with an academic press versus a trade press?

Petty: My assessment is somewhat skewed, as it’s based on the experience of working for two independent nonprofit publishers with strong academic programs before I joined Northwestern.

At South End Press, the publishing collective where I was an editor/publisher in the 2000s, we published nonfiction titles that appealed to activists, teachers, university professors, community organizers, students, and other interested readers. Our sales were, roughly, split down the middle between academic and trade markets.

At Beacon Press, one of the few AAUP publishers that is not a university press, we specialized in “crossover” titles—books that found homes with general readers and in classrooms. But independent publishers like SEP and Beacon are exceptional. Trade publishers, in the main, are powered by the search for blockbuster sales, not commitments to radical social change; public dialogue; or the desire to forward “academic contributions.”

While a first-time author who signs with a trade press may enjoy a larger advance, their book may not get the editorial attention it needs—staff time may be allotted to books that are seen as more profitable. Furthermore, trade publishers are typically focused more on publicizing frontlist (i.e. current) titles, than in marketing efforts (such as conferences, direct mail, emails, and other targeted appeals) that maintain the relevance of books long after publication.

Blain: In terms of preparing the book proposal, what are the key differences between a proposal for a trade press and one for an academic press?

Petty: I’m speaking very broadly here, but trade proposals generally emphasize selling points, including the author’s visibility and platform, via social media and/or organizations. Somewhat paradoxically, a trade proposal must prove there is a market for a book—usually through providing a list of comparable titles that have sold well—while also arguing for the book’s singularity. While scholarly proposals often advance “time-specific” books, trade proposals position “timely” projects. Finally, the proposals envision specialist readers or lay readers, and the language used reflects these different audiences.

Blain: What are some of the best practices for prospective authors to develop a positive relationship with acquisitions editors? How should one prepare for the initial meeting?

Petty: Relationships between authors and editors are unique. Along the way, from proposal through publication, they act as teachers and students to each other—sometimes at the same time, all at once! In the very best situations, we’re working in solidarity with each other. Practically speaking, your editor often remains your best press contact, helping you to navigate your book’s production and to support marketing and publicity work after publication.

During your first meeting with an acquisition editor, you should be prepared to speak clearly and persuasively about how your book will extend, challenge, and/or subvert assumptions in your field, and to discuss comparable titles as well. Also, like trade publishers, university publishers rely on authors’ connections for marketing and publicity opportunities. If you have a clear idea about who your readers are—and some suggestions about how to reach them—it may help your project stand out from the pack. It’s good to have different versions of your “elevator pitch” ready!

If you don’t meet an editor in person, be prepared, direct, and respectful on phone or email. Do be succinct—it’s best not to send 20 emails when one will do! But as you get further along in the process, it’s appropriate and helpful to ask about timelines and agendas—if you don’t know what to expect, ask!

Blain: As a new editor at Northwestern University Press, you will be supervising NUP’s trade list. Can you tell us more about this new position? What kind of projects would you like to acquire? Are there specific topics that align with your publishing goals for the next three to five years?

Petty: I’m very excited about my new position—I have a robust portfolio! I acquired books in education, policing, health, and social movements at Beacon, and I’m continuing to work in these areas at NUP. As I shape the trade list, I’m also commissioning books that build on our strong African American list, led by some truly incredible poets and outstanding regional writers, and the scholarly work done by authors in our Critical Ethnic Studies Association series, Critical Insurgencies, certainly informs my acquisitions.

Another plus is that I get to acquire titles about the city and the region. Even though I’ve lived out east and down south, I’m a Midwesterner. I’m a native Chicagoan—I was born and raised here—and I attended college in Iowa. It’s a gift to tap the very deep well of wisdom and talent here.

I’m commissioning for our Curbstone imprint, which features creative nonfiction, memoir, fiction, and poetry that emphasizes human rights and social justice; our TriQuarterly imprint, which has published the work of leading novelists and poets for more than 30 years; and literature in translation for our Northwestern World Classics imprint. I’m already working on projects by well-known Haitian and Puerto Rican writers for NWC, and I’m excited to make this list more expansive.

Working directly with creative writers—primarily novelists and playwrights—feels especially gratifying, as I’m returning to my first love. I studied English and Women’s Studies at Grinnell. Since earning my MA in English and Certificate in Feminist Studies from Duke, I have continued to teach literature in prisons, community colleges, and adult education programs. It’s a welcome development to turn to these genres as an editor.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

For Liberal Arts Ph.D programs, your excellent advice should be required reading — and perhaps even a seminar/workshop for advanced dissertation students. The process from dissertation to book ( trade or academic) should be less formidable and understandable. This is a useful step in the right direction.

Al-Tony Gilmore, Ph.D

Historian Emeritus

National Education Association

Thank you Al-Tony!

Much appreciated.

Jill Petty

Gonna stick this entire article on my vision board.