Free the Beaches: A New Book on the Fight for Racial Equality in Connecticut

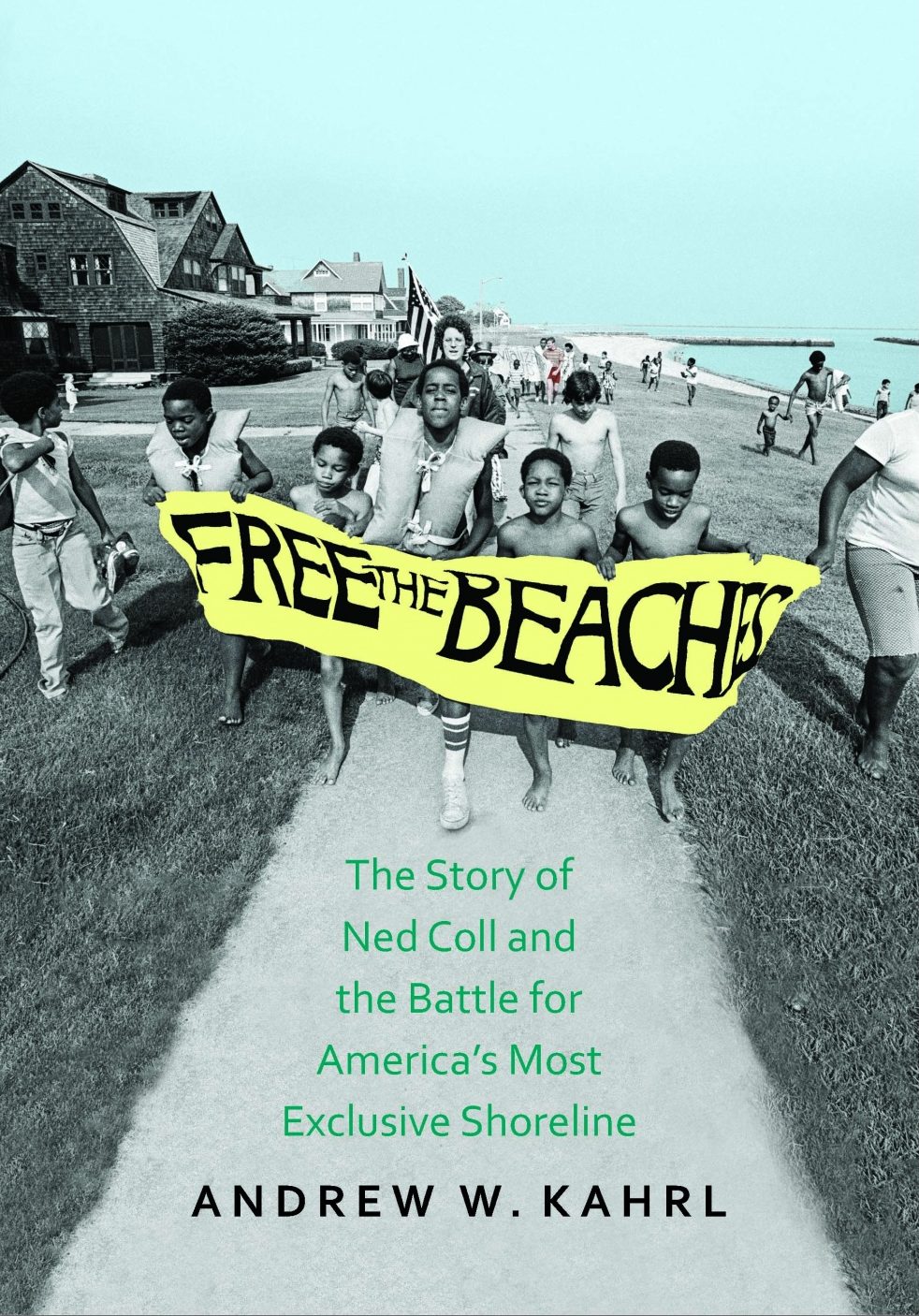

This post is part of our blog series that announces the publication of selected new books in African American History and African Diaspora Studies. Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline was recently published by Yale University Press.

***

The author of Free the Beaches is Andrew W. Kahrl, Associate Professor of History and African American Studies at the University of Virginia. He specializes in the social, political, and environmental history of race and real estate in the twentieth-century US. He is the author of the books Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline (Yale University Press) and The Land Was Ours: How Black Beaches became White Wealth in the Coastal South (University of North Carolina Press). He has also published articles in the Journal of American History, Journal of Urban History, Journal of Southern History, Critical Sociology, and Southern Cultures. Kahrl’s new book, Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline, tells the story of controversial protester, Ned Coll, who gathered determined African American mothers and children in hopes of challenging the racist, exclusionary tactics of homeowners in Connecticut. Follow him on Twitter @andrewkahrl.

The author of Free the Beaches is Andrew W. Kahrl, Associate Professor of History and African American Studies at the University of Virginia. He specializes in the social, political, and environmental history of race and real estate in the twentieth-century US. He is the author of the books Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline (Yale University Press) and The Land Was Ours: How Black Beaches became White Wealth in the Coastal South (University of North Carolina Press). He has also published articles in the Journal of American History, Journal of Urban History, Journal of Southern History, Critical Sociology, and Southern Cultures. Kahrl’s new book, Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline, tells the story of controversial protester, Ned Coll, who gathered determined African American mothers and children in hopes of challenging the racist, exclusionary tactics of homeowners in Connecticut. Follow him on Twitter @andrewkahrl.

During the long, hot summers of the late 1960s and 1970s, one man began a campaign to open some of America’s most exclusive beaches to minorities and the urban poor. That man was anti-poverty activist and one-time presidential candidate Ned Coll of Connecticut, a state that permitted public access to a mere seven miles of its 253-mile shoreline. Nearly all of the state’s coast was held privately, for the most part by white, wealthy residents.

This book is the first to tell the story of the controversial protester who gathered a band of determined African American mothers and children and challenged the racist, exclusionary tactics of homeowners in a state synonymous with liberalism. Coll’s legacy of remarkable successes—and failures—illuminates how our nation’s fragile coasts have not only become more exclusive in subsequent decades but also have suffered greater environmental destruction and erosion as a result of that private ownership.

“What would it mean to broaden our view of the most important fights against segregation from a Montgomery bus to the Connecticut shore? Andrew Kahrl powerfully shows us and it’s sobering: the extent Northern white families went to preserve their segregated spaces and the long fight by black and white activists like Ned Coll and Revitalization Corps to open them.” –Jeanne Theoharis, Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Brooklyn College

Keisha N. Blain: Please share with us the creation story of your book — those experiences, those factors, those revelations that caused you to research this specific area and produce this unique book.

Andrew W. Kahrl: As I was conducting research for my first book, which explored history of African American beaches and coastal landownership and development in the South, I kept finding newspaper articles and other sources that mentioned a white social activist in Connecticut who was waging a one-man fight to open up the state’s shoreline to the public and calling attention to what he saw as the racist motives behind the ostensibly color-blind beach access restrictions common throughout the northeast. My discovery of this forgotten activist who had fought against racial segregation in New England coincided with the publication of a number of groundbreaking works on Jim Crow and the struggle for civil rights in the North, notably Thomas Sugrue’s Sweet Land of Liberty, Matthew Countryman’s Up South, and the edited collection Freedom North by Jeanne Theoharis and Komozi Woodard, all of which inspired me to delve more deeply into the history of race and inequality in Connecticut, a place that had previously attracted scant attention from historians.

I was also drawn to this story out of an abiding interest in the relationship between social and environmental inequality, in particular, the interests behind and impact of exclusionary land use policies on people and the environment. In Connecticut, as I soon discovered, exclusionary beach access policies (which had, by the 1960s, rendered almost all of the state’s shoreline off-limits to the general public) complemented and reinforced racial and class segregation in housing markets, schools, and public life, and inflicted significant and lasting damage to the shoreline itself. In the course of studying Ned Coll, I also began to look more closely at the open beaches movement of the 1960s and 70s. During these decades, activists across the country were fighting to tear down the numerous barriers wealthy municipalities and private homeowners had erected and restore the public’s ancient right to the sea. However, with the exception of Ned Coll, few of these activists were calling attention to the racially discriminatory motives and racially disparate impact of beach access restrictions, much less linking the fight against privatization of public space to the broader struggle for a more inclusive and integrated society.

Ultimately, I wanted to write a history that spoke to and shed new light on the two most critical problems we as a society face today: economic inequality and climate change. Connecticut is, by some measures, the most unequal state in America, a place of fabulous wealth and dire poverty. Furthermore, it is a place where those two extremes have, for decades, been kept separate and apart by a host of land-use policies and practices. Resident-only and private beaches were, in this respect, one among many exclusionary devices that helped make the state so profoundly separate and unequal. Moreover, they were also the one that had the most direct and negative impact on the environment, both because they led to the proliferation of environmentally destructive barriers meant to keep the public out, and, more critically, because they facilitated private beachfront development. This, then, fostered a culture of political localism in shoreline towns that today stand squarely in the way of more sensible, sustainable coastal land use policies in the future.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.