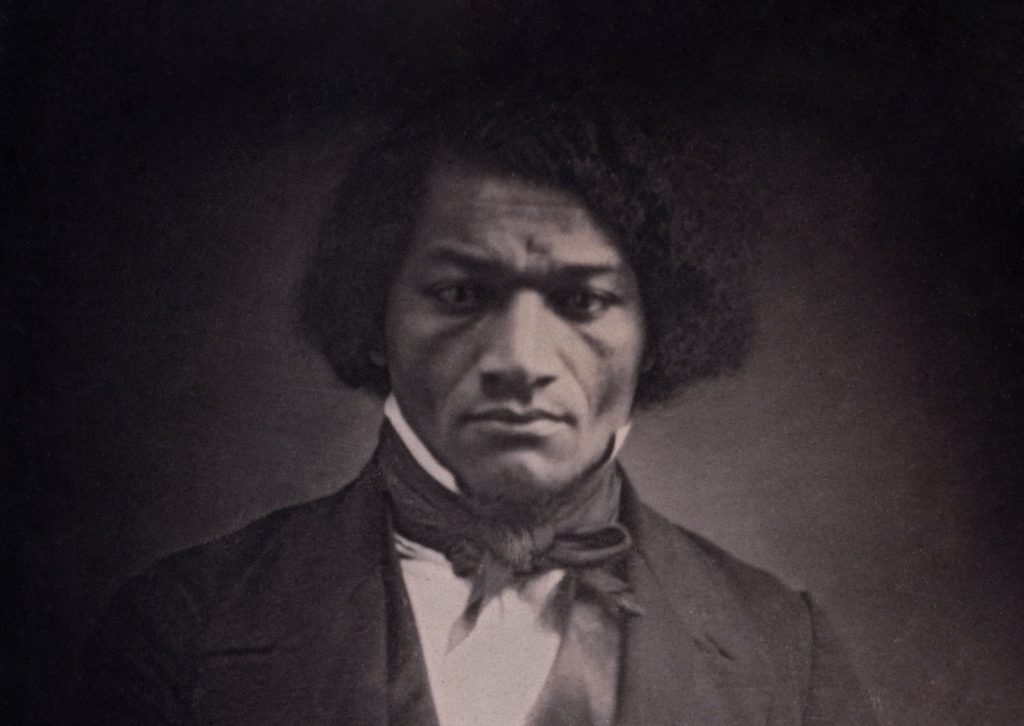

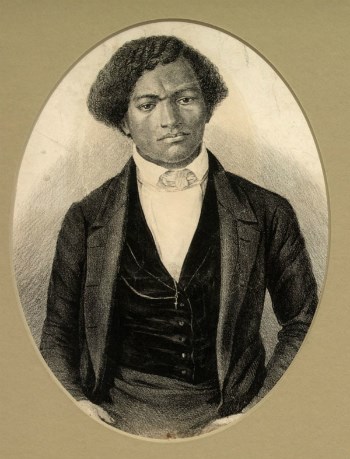

Frederick Douglass’s Childhood of “Extremes”

*This post is part of our online forum on the life of Frederick Douglass.

Frederick Douglass possessed an extraordinary memory. By all accounts, and from the evidence of some of his special privileges, the youthful Frederick Bailey was remarkably bright, his powers of observation active and acute; he impressed those around him as smart and curious beyond his years. The detail of his autobiographies can to some extent be attributed to such sheer intelligence. But other factors were surely as important in his remarkable recall. Eventually, the fugitive slave of 1845, as well as the more politically mature Douglass of 1855, knew he needed veracity beneath this story for it to be creditable in a world that doubted any literary acumen or basic intelligence in Black people. Even more, from his first moments as a speaker in his early twenties, a mere two or three years out of slavery, Douglass rehearsed over and over the stories he would eventually write up in the Narrative and revise in Bondage and Freedom. Memory is a mysterious and infinitely powerful if unwieldy human device. With enough prompts and associations, a great deal of childhood memory, both difficult and pleasing, can be retrieved as it is refashioned. Douglass made as well as received his own story from memory; he summoned it with both private and public repetition for an audience he knew he had to persuade.

In Bondage and Freedom, Douglass disingenuously declares: “let others philosophize; it is my province here to relate and describe; only allowing myself a word or two… to assist the reader in the proper understanding of the facts narrated.” Hardly. Douglass’s autobiographical representation of his early life as a slave is a thoroughgoing abolitionist manifesto, a penetrating portrait of the inner and exterior worlds of both slaves and slaveholders. And he may, indeed, have seen or certainly heard a good deal about all that he wrote. The blood that flows in what he called his “chapter of horrors” is full of philosophy as well as psychology.

Douglass had either witnessed or learned from hearsay at least seven brutal whippings or murders by the time he was eight years old. And this does not include the casual violence he saw from overseers, from the wretched Aunt Katy around the Wye House kitchen, or from his first instructor in religious devotions, a slave named “Doctor Isaac Copper,” whom Douglass turned into a “tragic and comic” character in his autobiography. Copper was a cripple, who with hickory switch in hand, forced groups of children to learn the Lord’s Prayer, as he also whacked them with his whip. “Everybody in the south,” wrote Douglass, “wants the privilege of whipping somebody else. Uncle Isaac shared the common passion of his country.” Shortly after memorizing “Our Father who are in heaven,” Douglass quickly became a “truant” from Copper’s devotions. Details flowed in his recollections, pain and adventure tucked away in the secret garden of his memory. His great indictment of slavery came first and foremost from the accumulated injury of his own story.

Douglass made a careful study of the range of overseers he had known, from the sadistic to the reluctant to those who enacted violence as mere “policy” in the “system.” His master, Anthony, seemed to be the company man enforcing policy, except when sexually scorned; then he joined the darkest side. But under Anthony’s general command were two other overseers named William Sevier (pronounced Severe) and Orson Gore (Douglass mistakenly identifies him as Austin Gore). These were not names invented by a novelist writing a prurient potboiler; they were real, hardened, paid accessories to slavery’s crimes on the Wye plantation. One day near the slave quarters, Frederick heard noise and screaming. As he sauntered over to the scene he witnessed Nelly Kellem, a tall, strong slave woman being wrestled and dragged toward a tree by Sevier. Nelly gave as good as she got in this fight, clawing Sevier’s face with her nails and hitting him as hard as he hit her. According to Douglass, three of Nelly’s five children witnessed this bloody fracas, as the “monster” finally managed to subdue the woman and rope her to a tree. As the children screamed “Let my mammy go!,” Sevier shouted foul curses and, like a “savage bulldog,” beat Nelly to a bloody pulp, while the woman took the blows with fierce and indignant courage. As Douglass wrote of this event years later, he implied that the worst part for him was not Nelly’s “back… covered with blood,” but the “sounds” of her screams “mingled with those of the children.” The senses that trigger deep emotion are crucial in what stays in the memory; in this case sounds haunted a young boy’s vision of the world ahead of him.

Such was young Frederick’s prolonged initiation into the world of human relationships, to notions of fairness and morality, of crime and punishment, of familial bonds and fissures. Overseers were the law enforcers and the courts. Nelly’s offense that led to her bloody beating in front of her traumatized children was the ubiquitous slave crime of “impudence.” The moral Douglass the abolitionist-propagandist drew from the story was that Nelly—as a woman—had stood her ground as long as she could. She left the ugly Sevier scarred in his already deformed face. Her bravery, something he would later claim for himself, proved the doctrine Douglass invoked with excessive bravado: “He is whipped oftenest, who is whipped easiest.” That stirring statement, while manly and inspiring, has the air of smugness, offered from a safer position as author of his memoir many years after watching the slaves on the Wye estate live with the daily, frightening grind of comprehending just who could muster such courage to resist and who could not. He could hardly offer us, or himself, any sense of what the bleeding Nelly told her sickened children that evening in the quarters. Fighting back was noble and possible; but Douglass also left the distinct impression that Eastern Shore slavery was a daily experience in which even a child began to understand that sanity itself, as well as physical survival, might be at stake.

At the stables at the Wye plantation, Douglass observed, “a horse was seldom brought out… to which no objection could be raised” by either Lloyd himself, or by his sons and sons-in-law. Old Barney, the head groom and stable hand, had to endure these barbs and humiliations. One day, Colonel Lloyd was especially displeased with the appearance of one of his riding horses and took it out on Barney. He ordered the “bald and toil-worn” man to kneel on the ground, and laid “thirty lashes with a horse whip” on his bare shoulders. Barney “bore it patiently, to the last, answering each blow with a slight shrug of the shoulders, and a groan.” This incident especially “shocked me at the time,” Douglass remembered, not it appears for the blood drawn, but for the unspeakable humiliation of an old man of dignity and talent by the master himself. The “spectacle” of the beating of Barney, said Douglass, revealed slavery in its “maturity of repulsive hatefulness.” In a child’s eyes, and memories, something sick, fearful, or evil seemed to lurk around the corner of every building, in the sounds of every overseer’s steps at the Wye enterprise. Long after he had left the Eastern Shore behind, such a prospect haunted Douglass as he harbored real needs for retribution.

“Such is the constitution of the human mind,” Douglass wrote in 1855 while trying to capture his state of mind as an eight and nine year old on the Wye plantation, “that, when pressed to extremes, it often avails itself of the most opposite ends. Extremes meet in mind as in matter.” With a probity unmatched by any other slave narrative author, he remembered and analyzed a world of stark opposites, all but unalterable extremes which he had to learn to understand, navigate, and survive. As his awareness grew of his predicament, Frederick became a thinking being trying desperately to preserve and protect his mind as well as his body from internal disintegration and external destruction. At every turn in his life as a slave, both mind and body were in constant danger. His mind, he learned, he could cultivate and protect more easily, with more self-control, than his body.

Douglass’s experiences began to shape a disposition, a set of habits of mind, a personality that may have lasted all of his life. He was forever in search of a sense of “home,” a concept he dwelled on at length in the autobiographies. He was capable of great love and compassion, but perhaps even more desperately in need of receiving love and compassion long into adulthood. He experienced great difficulty trusting other people, even those who seemed to be friends. With mixed results, he sought time and again to find parental figures in whom to invest his faith and from whom to garner emotional sustenance. And his was a childhood, he admitted, blessed with several turns of good fortune altogether uncommon to slaves, while at the same time we should not doubt that he carried with him from his youth a profound sense of rage against the violence and degradation he both witnessed and experienced. If a slave was thoughtful, and dreamed of something better, Douglass believed, he must endure these extremes. Although crafty and guarded as a writer, he nevertheless revealed a childhood laden with the traumas unique to slavery. Those traumas were a kind of emotional furniture in his psyche; he would forever try to control and rearrange them in differing orders, but he could never fully expunge them. That emotional furniture may have darkened his outlook, but it also provided the wellspring of his great personal story. Douglass made “the nature and history of slavery” his youthful “inquiry,” he maintained. We are led as his readers on the journey of an evolving, brilliant mind’s bitter questioning of all around him. “Why am I a slave,” he asked so innocently in Bondage and Freedom? “Why are some people slaves, and others masters?” he demanded to know, as though representing a child’s voice. This “subject of my study… was with me in the woods and fields; along the shore of the river, and wherever my boyish wanderings led me.”

As autobiographer, Douglass sometimes portrayed himself as just out of the frame of the picture, observing, studying, accumulating all that “knowledge” that not only might free him, but also persuade his audience of the merits of the antislavery cause. Long before the age of psychology, Douglass provided a portrait of a young slave conducting psychological warfare against slavery, as that system itself conspired in every way to ensnare, and ultimately destroy him. His powers of recollection, fashioned beautifully into words, became his only available weapon. In words, Douglass always fought back not only to defeat slavery, but to make sense of its extremes and work through his pain. “Why am I a slave” is an existential question that reflects as well as anticipates many others like it in human history. Why am I poor? Why is he so rich, and she only his servant or chattel? Why am I hated for my religion, my race, my sexuality, the accident of my birth in this valley, or that side of the river, or on this side of the railroad tracks? Why am I a refugee with no home? Why do craven, empowered men control the U. S. Senate? Douglass’s story represents so many others over the ages.

Douglass wanted us to believe that as a child he gained inner strength and self-knowledge from his sufferings. With caution for his skilled literary invention, we ought not doubt most of what he claimed as an amateur child psychologist. Every student of Douglass tries to discern what in his memoirist’s voice was real and what was merely literary. Yet, the two were almost always mixed for this gifted artist.

Douglass’s world of extremes flowed from his memory in sheer description as well as in metaphors of explanation. Most of the time he kept himself squarely within the frame of his canvass. He identified “hunger” and “cold” as his primary sufferings at the Wye plantation. He spent every day “almost in a state of nudity,” wearing his “tow-linen” hanging down to his knees. He stayed on “the sunny side of the house” or in “the corner of the kitchen chimney” in winter to find warmth. At the Anthony house, the slave children, “like so many pigs,” ate corn meal “mush” out of a “large wooden tray, or trough,” laid down on the floor of the kitchen or on the ground outdoors. An oyster shell was the only substitute for a fork or spoon he had ever known until he moved to Baltimore. He slept in a closet, he tells us, and in extreme cold, he would steal a bag used for carrying corn to the mill, and with “head in and feet out,” fitfully sleep on January and February nights. There were “no beds” or “blankets” for the slave children.

We must imagine Douglass the twenty-seven year old writer, sitting at a desk in his small, crowded apartment in Lynn, Massachusetts in the winter of 1844-45, drafting his first autobiography. As he recollected these physical hardships of his childhood, his feet presumably warm enough, Douglass mingled past and present and announced his suffering and his literacy in an unforgettable metaphor: “My feet have been so cracked with the frost, that the pen with which I am writing might be laid in the gashes.” Memory is almost always a combination of retrieval and invention. The corn sack, a child’s frozen feet, and the pen of an adult writer as a kind of medicinal weapon to cure the gashes not only in his feet but in his psyche, helped Douglass explain the meaning of being a child slave, as well as the freedom he pursued as a writer and in reality.

*This post is based on David Blight’s new book, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

I thank you for this reminder and affirmation of the significance of Frederick Douglass and his stories; that the horror of enslavement in this country may never be forgotten, and that we might see it boring through the centuries to reach us with its loathsome tenacles in every decade.