François Duvalier and the Misuse of Martin Luther King, Jr.

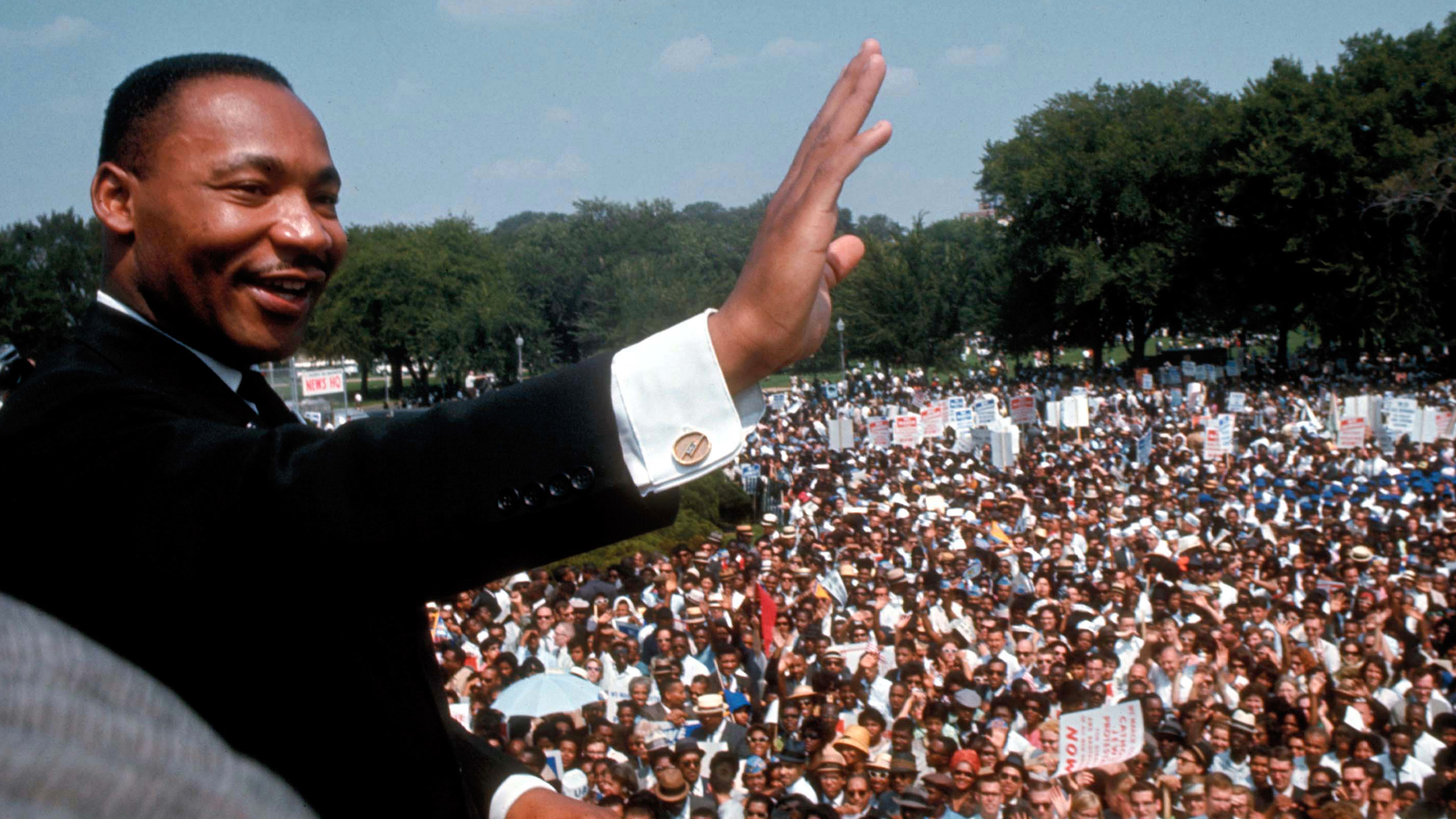

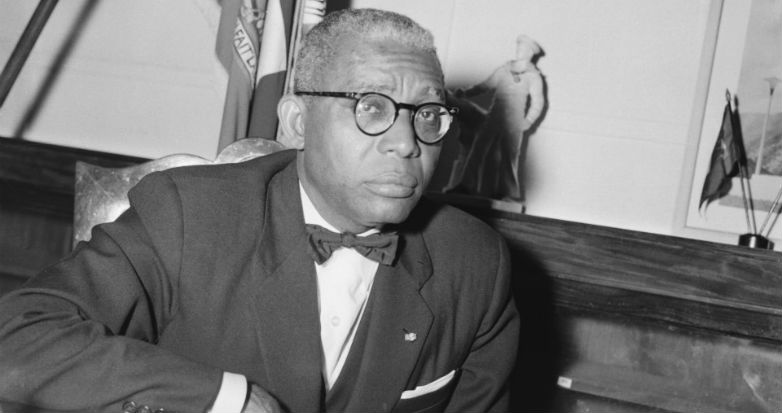

On the morning of April 9, 1968, the Haitian political elite joined the US diplomatic core in the Port-au-Prince Cathedral. Along with hundreds of other attendees, they came not just to mourn Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. but to exalt François Duvalier. During the funeral mass, Father Joseph Attis started his eulogy by celebrating the “opportunity to pay an ultimate tribute to ‘one of the most prominent men of genius of the Race,’ while at the same time laying emphasis on the nobility of character of the Lifetime Head of the Nation who thought of requesting this funeral service.” He lamented that King was assassinated. But King’s struggle lived on in Duvalier, “the President for Life of the Haitian Nation, a king-hearted Man smitten with Social Justice and Brotherly Love.”1

The funeral mass ordered by Duvalier was not evidence of his admiration for King. Instead it was part of a thinly-veiled attempt to humanize his inhumane regime. By espousing Pan-Africanism—the belief that all people of African descent share a common past, collective struggle, and destiny—and publicly mourning a Black leader known across the world for his philosophy of non-violence, Duvalier tried to re-affirm Haiti’s place at the vanguard of the global Black freedom struggle and divert attention from the violence of his dictatorship. His propaganda accomplished neither goal but did presage his enduring efforts to appropriate King.

Born on April 14, 1907, François “Papa Doc” Duvalier was part of the generation of Haitians shaped by their formative years fighting against the US occupation (1915-1934). During the occupation, the US Marines not only exported racial segregation from the United States to Haiti but also gave preference to light-skinned Haitians for jobs within the puppet Haitian government. In response the literary, cultural, and political mouvement indigéniste emerged. For indigénistes including Jean Price-Mars, the military occupation showed that the Haitian elite had made a colossal mistake in representing themselves as “colored Frenchmen.” They argued that Haitian leaders had suppressed their African heritage. They had distanced themselves from their country’s dual (French and African) character and the cultural basis of its sovereignty.

Black Haitian nationalists including Duvalier took those ideas based in a desire for national unity to ideological extremes. During the final years of the occupation, Duvalier, a former pupil of Price-Mars at the Lycée Petion and a current student at the School of Medicine in Port-au-Prince, joined a group of budding Black intellectuals interested in Haitian history, culture, and politics. They became known as the Griots. Deriving their name from the class of West African storytellers, the Griots espoused noirisme, an anti-liberal and anti-Marxist political and cultural ideology that equated authentic Haitian identity with blackness. According to noiristes Haiti had to be governed by Black leaders who represented the country’s Black masses not the interests of light-skinned elites. Noirisme had to elevate Vodou as the fundamental link between Haitians and Africa while marginalizing or even suppressing mulâtrisme and Marxism, regarded as twin enemies of the state.

Noirisme emerged as a powerful force in Haitian politics in the two decades after the occupation, but its full authoritarian implications became clear in September 1957 with Duvalier’s election to the presidency. After seizing power through electoral fraud, suppression of political opposition, and belated support from the US government wary of the prospects of Communism in Haiti, Duvalier quickly reduced the size of the Haitian army. He then organized the Tontons Macoutes. Named for a mythical bogeyman who kidnapped misbehaving children at night and stored them in his knapsack, the Macoutes were a private paramilitary force that terrorized with personal approval from Duvalier. They stole from, raped, and murdered tens of thousands of Haitians, often delivering their innocent victims (supposed political enemies) to torture and death in the notorious prison, Fort Dimanche.

For Duvalier the practice of Pan-Africanism became a way to situate Black power or liberation rather than wanton violence as the foundation of his noiriste regime. Having suppressed several plots against him and declaring himself president-for-life, Duvalier welcomed Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie to Haiti in 1966. The visit of Selassie, the founder of the Organization of African Unity and the lone foreign head-of-state to come to Duvalier’s Haiti, was purely political theater. Haitian newspapers subjected to the censorship of the Duvalier regime celebrated the “Haitian-Ethiopian friendship” and printed speeches where Duvalier re-affirmed his country’s historical position at the vanguard of the struggle for Black and Third World liberation. The media repeated Duvalier’s claims to Selassie that Haiti was not only a historical “paladin of liberty” but also a country that made common cause with Ethiopia in the “crusade for the total triumph of man.”2

Duvalier furthered that propaganda two years later after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968. While Coretta Scott King grieved the death of her husband, the Haitian dictator sent her condolences and declared a national period of mourning in Haiti. For four days the Haitian flag flew at half-mast, theaters closed, and radio stations played music deemed suitable for the somber occasion.3 Funeral masses took place throughout Haiti, not just in the capital Port-au-Prince. As the Tontons Macoutes loomed over attendees at those services, Duvalier put the hurried, finished touches on Hommage au Martyr de la Non-Violence: Le Révérend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. An English translation of the work that begins with Duvalier’s curriculum vitae quickly followed.

Obsessed with real and perceived threats to his power, Duvalier made little attempt to hide the repressive goals of commemorative acts that soon transcended public rituals of mourning. Along with the other tributes given to King after his assassination, the Haitian postal service issued a series of stamps in King’s honor and the Port-au-Prince city council changed Ruelle Nazon, one of the city’s main streets, to Avenue Martin Luther King. Duvalier was transparent in his rationale for these efforts. On April 22, 1968, Duvalier, later writing that he and Haiti were still reeling from the “brutal assassination of the apostle of non-violence,” told Haiti’s National Assembly that his country retained “the moral and spiritual leadership of the Black World.” He used King’s death to warn against internal dissent by stressing that Haitians had to show “our internal cohesion so that our [B]lack brothers in the world may have their eyes, mind and soul riveted to the noble ideals of human brotherhood, solidarity and love which Haiti nurses and offers (emphasis mine).”4

In subsequent interviews with the US press, Duvalier used King’s death not only as a chance to advance noiriste politics within Haiti but also to strengthen the international image and relations of his regime. Less than a month after King’s assassination and one week after Duvalier sent a message to the annual meeting of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church extolling King and calling for Black unity under Haitian leadership, the Haitian dictator gave an interview to a correspondent of The Miami News. Motioning toward a photograph of King that hung behind his desk next to portraits of Selassie and US President Lyndon B. Johnson, Duvalier told his interviewer that King was “a great man” and recalled Haiti’s public commemorations of the martyred activist. He appropriated King’s philosophy of non-violence, too. “It is important, peace. To be left alone by outside interests. Not to have violence,” Duvalier was quoted as saying. “I own the tape of his speech, ‘I Have a Dream.’ I play it often. Yes, Peace.”5 To Duvalier peace and non-violence meant non-intervention. Both required continued support rather than scrutiny from the United States which, under Johnson, sent millions of dollars to Duvalier because it was more concerned with Communism than the well-being of Haitians.

While it was Duvalier’s self-presentation as a staunch anti-Communist that was the most profitable propaganda for his dictatorship, there is equal significance in his appropriation of King. Duvalier who died of heart disease in April 1971 was, like other authoritarians across time and place, remarkably adept at manipulating his nation’s history and culture to legitimize his power. He did not stop at misusing the image of Jean-Jacques Dessalines or the spirits of Vodou, however. By manipulating Pan-Africanism and claiming unassailable leadership of the global Black freedom struggle through the mourning of King, Duvalier acknowledged the power of King’s symbolism even in the immediate aftermath of his assassination. In fact, Duvalier’s actions foreshadowed the ease with which US reactionaries who opposed King’s actions and ideas would also reinforce repressive policies by pretending to have inherited the late activist’s dream.

Ultimately Duvalier’s misuse of King provides an urgent lesson. As King’s radical substance slips further into hollow symbolism, the burden is on historians to capture King as he lived and challenge commemorations in which he is misremembered. To do otherwise not only risks ceding the field of historical memory but also emboldening opponents of King’s actual vision.

- François Duvalier, A Tribute to the Martyred Leader of Non-Violence: Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Special Edition, trans. John E. Pickering. Translator (Port-au-Prince: Presses National, 1968), 90-91. ↩

- “L’Important Discours du Président à Vie François Duvalier,” Le Nouvelliste, April 25, 1966. ↩

- “Condoléances du Président Duvalier à Mme M.L. King. Un Deuil National de 4 jours est décrété,” Le Nouvelliste, April 6, 1968. ↩

- Duvalier, A Tribute to the Martyred Leader of Non-Violence, 109. ↩

- “‘Papa Doc’s’ Grip on Haiti Strong; Natives Keep Faith,” The Miami News, May 4, 1968. ↩

Hey Brandon,

This is a really important piece and quite timely, especially given Trump’s most recent ridiculous set of comments. Given that, I remember one talking head completely dismissing that the US has played any role in the state of affairs in Haiti. Might you or someone else write a quick short piece outlining the impact of US relations with Haiti from the occupation to our support of Papa and Baby Doc and beyond? But really thanks for THIS unique take on King

Thanks for reading, Davarian. I touch on that impact, briefly, here: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/made-by-history/wp/2018/01/14/racism-has-always-driven-u-s-policy-toward-haiti/?utm_term=.8b10dfa81dfb. Also, H-Haiti has compiled a list of responses to Trump’s anti-Haitian comments (https://networks.h-net.org/node/116721/discussions/1250418/list-responses-president-trumps-latest-racist-comments-about#reply-1257234). A good start but more to be done, always.