Forging Black Identities in Slavery and Freedom: An Interview with Alex Borucki

This month, I interviewed Alex Borucki about his new book, From Shipmates to Soldiers: Emerging Black Identities in the Río de la Plata (University of New Mexico Press, 2015). Reconstructing the social networks of Africans and their descendants in Montevideo and Buenos Aires, Borucki reveals how enslaved and free black people forged new relationships and identities through the shared experiences of the Middle Passage, serving in colonial militias, and participating in urban associations. He situates the emergence of black social life in Montevideo and Buenos Aires in the context of the transatlantic and inter-American slave trades as well as the shifting political environment in the Río de la Plata from the colonial period to the early independence era. This post is part of an ongoing series of interviews with authors of new books in the field of Afro-Latin American and Caribbean history.

This month, I interviewed Alex Borucki about his new book, From Shipmates to Soldiers: Emerging Black Identities in the Río de la Plata (University of New Mexico Press, 2015). Reconstructing the social networks of Africans and their descendants in Montevideo and Buenos Aires, Borucki reveals how enslaved and free black people forged new relationships and identities through the shared experiences of the Middle Passage, serving in colonial militias, and participating in urban associations. He situates the emergence of black social life in Montevideo and Buenos Aires in the context of the transatlantic and inter-American slave trades as well as the shifting political environment in the Río de la Plata from the colonial period to the early independence era. This post is part of an ongoing series of interviews with authors of new books in the field of Afro-Latin American and Caribbean history.

Dr. Alex Borucki is Associate Professor of History at the University of California at Irvine. He completed his undergraduate studies at the Universidad de la República in Uruguay and holds a Ph.D. in History from Emory University. He is the author of Abolicionismo y tráfico de esclavos en Montevideo tras la fundación republicana, 1829-1853 (2009) and the co-author of Esclavitud y trabajo: Un estudio sobre los afrodescendientes en la frontera uruguaya, 1835-1855 (2004). His articles have appeared in numerous academic journals, including the American Historical Review, Hispanic American Historical Review, Slavery & Abolition, Itinerario, and Colonial Latin American Review. He is the co-PI, along with Dr. Gregory O’Malley, of the NEH-funded project, “Final Passages: The Intra-American Slave Trade Database.” For the 2016-17 academic year, he has received the NEH John Carter Brown Fellowship to support archival research for his next book, Slaves, Silver, and Atlantic Empires: The Slave Trade to Spanish South America, 1660-1810.

***

Reena Goldthree (RG): From Shipmates to Soldiers reconstructs the social worlds of Africans and their descendants in the Río de la Plata region of South America (present-day Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay) from the colonial period to the early independence era. Despite the region’s role in the slave trade, the Río de la Plata has not figured prominently in studies of New World slavery and is often overlooked in histories of the African Diaspora. What led you to this topic? What new insights can we gain by studying the Río de la Plata?

Reena Goldthree (RG): From Shipmates to Soldiers reconstructs the social worlds of Africans and their descendants in the Río de la Plata region of South America (present-day Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay) from the colonial period to the early independence era. Despite the region’s role in the slave trade, the Río de la Plata has not figured prominently in studies of New World slavery and is often overlooked in histories of the African Diaspora. What led you to this topic? What new insights can we gain by studying the Río de la Plata?

Borucki: I am actually from the Río de la Plata and I completed my pre-Ph.D. education in Uruguay. Before moving to the United States, I published a couple of books on slavery in the Río de la Plata during the early 19th century.

When I came to the United States in 2005 to do my PhD, I wanted to study slave resistance. However, I realized that “resistance” had been the big word in slavery studies for the past fifteen years. Therefore, I felt that I was simply reinventing the wheel. By doing new archival research in both Montevideo and Buenos Aires, I realized that the same group of black leaders appeared in sources about Catholic confraternities and free black militias. That led me to revamp my entire perspective on resistance in order to see how social networks from one specific aspect of the black experience overlapped with other aspects and how these social networks shaped identities. I began to examine how shared experiences shaped how Africans and their descendants thought about themselves as part of a collectivity.

What distinguishes my work from others in the context of slavery or the African experience in colonial Latin America is that you generally see a book on black confraternities, and everything is related to the experience of Catholicism and social networks within the confraternities. Likewise, you will have a separate book on free black militias or a book totally focused on cabildos. In my book, I tried to track how these different sets of experiences among the free and enslaved black population—in confraternities, militias, and other groups—were lived in connection to each other. People are complex today and we have to treat people as complex in the past as well. Also, I wanted to trace how the connected arenas of the black experience transition and change during the wars of independence in Buenos Aires and Montevideo.

RG: While the first enslaved Africans were transported to the Río de la Plata in the 1580s, you note that most enslaved Africans arrived between 1777 and 1812. During this period, appropriately 70,000 captives were transported to the region, with most disembarking in the port cities of Buenos Aires and Montevideo. Can you explain how the transatlantic and inter-American slave trades shaped the demographics of the black population in the Río de la Plata?

Borucki: After completing my dissertation, I published an article in the American Historical Review on the slave trade to Spanish America along with David Eltis and David Wheat. We discovered that some two million enslaved Africans arrived in Spanish America during the era of slave trade. Half of those two million captives—approximately one million people—were transported by Spanish slave traders, mostly to Cuba. Another half a million were transported by other foreign slave traders, such as the British, the French, the Dutch, and the Portuguese directly from Africa to various places in the Spanish Americas. And the remaining half million came from other colonies through a trans-imperial, inter-American slave trade, mainly from the British Caribbean to the Spanish colonies, from the Dutch Caribbean to modern-day Colombia and Venezuela, and from Brazil to the Río de la Plata.

The slave trade from Brazil to the Río de la Plata began with the foundation of Buenos Aires in 1580 and continued until the 1830s. It was 250 years of almost continuous slave trading across imperial borders between Brazil and Argentina and Uruguay. In early colonial Buenos Aires, from 1580 to 1640, 60% or 70% of the value of the city’s imports came from the traffic in enslaved Africans. In the late colonial period, from the 1770s to 1810, Buenos Aires and Montevideo not only provided enslaved people to the cities, but also to all the countryside and to an internal slave trade that stretched to Santiago, Chile and Lima, Peru.

The Spanish Río de la Plata was deeply connected to the Portuguese Atlantic and it was from that that some merchants from Montevideo and Buenos Aires launched their own trans-Atlantic slave trade going to Mozambique. Because the slave trade to the Río de la Plata involved traders from several nations, you have Africans coming to the region from very different areas of Africa. Like in Cuba, you have slave traders bringing captives from across the African continent—from Senegal all the way to Mozambique—to the Río de la Plata.

RG: You use Catholic Church marriage files to explore the social networks African captives forged during their journeys to the Río de la Plata. How did shipmate ties contribute to the formation of black identities in the region?

Borucki: There is an entire historiographical debate in the literature on slavery and slave cultures about shipmate bonds. In the historical record, you see these shipmate ties expressed in different languages: in English as “shipmates,” in Spanish in Cuba as “carabelas,” and in Brazilian Portuguese as “malungo” which originated from West Central African languages.

Free and enslaved African men, when they needed someone who they could trust to provide an account about their lives, sought out people who they knew from their past, either from a slave trade port or from the slave ship. Importantly, the slave ship was a deeply gendered space, where men shared a space with other men, and women shared a space with other women. This is how shipmate ties originated.

Men who wanted to marry in the Catholic Church first had to prove that they were single. They needed to provide witnesses to confirm that they were single, and most commonly, Africans provided witnesses who had been with them either in previous slave trade ports or who had come with them on the same slave ship. Also, it was not uncommon for enslaved Africans to encounter a family member or someone who they knew, either from Africa or from Brazil, in Montevideo because of the established slave trading routes. Frequently, the same slave trader connected one port in Africa with one port in the Americas.

RG: You argue that collective organizations—such as colonial militias, Catholic confraternities, and African-based associations—provided valuable social spaces and leadership opportunities for Africans and their descendants, particularly for men. These organizations also fostered the development of new shared black identities in Montevideo and Buenos Aires. How did gender shape the process of ethnogenesis in these groups?

Borucki: These organizations created collective identities beyond the casta system, the race thinking of the colonial era that predated the modern conceptions of racial difference. It’s from these organizations that you see both centripetal forces, forces that divide groups along different emerging leadership, but you also find centrifugal forces that put people together from the bottom up. For example, you see that some of the leaders of the African-based associations attempted to create large celebrations around the Day of Kings and tried to put themselves as the leaders of all the African associations of Montevideo. Or, you see that black letrados like Jacinto Ventura de Molina tried to carve a better place for themselves and the community within the limits of accommodation. They tested how far they could go within the deeply unequal colonial system.

These black males leaders also tried to unite their communities by using new language. In the colonial documents, some leaders used new labels such as “the Ethiopians and their descendants” or “the Black People.” The term “Ethiopian descendants” came from biblical language in which “Ethiopian” meant African. We know that Caribbean radicals of the mid to late 19th century used similar language, but I also found it in the Catholic setting of the Río de la Plata.

In terms of women, I have some evidence that women in black confraternities had their own branches. I have found evidence that some African-based associations in Montevideo in the 1830s and in Buenos Aires in the 1860s had queens. Unfortunately, I don’t have evidence of African women interacting with colonial officials or with national authorities following independence. The Catholic Church and the Spanish regime—and later, the leaders of the independent republics—only recognized men as valid go-betweens.

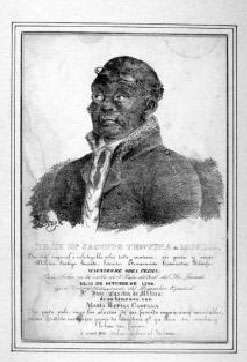

RG: In the final chapter of the book, you explore the remarkable life of Jacinto Ventura de Molina (1766-1841), an educated free black letrado and militia officer in Montevideo. As you note, Molina maintained ties with white elite patrons as well as participated in Montevideo’s African social networks. How was Molina able to navigate his role as a “mediator for black communities” while also participating in Montevideo’s white-dominated lettered world?

Borucki: Jacinto Ventura de Molina was exceptional, but he was not unique. What is unique is that his manuscripts have survived and that they are housed in a national library. There were different capacities, abilities, and degrees of engagement by both enslaved and free black people with the lettered culture of colonial Latin America. When you comb through the archive, you discover that there were enslaved people who could write or who could read but could not write, and sometimes you find enslaved individuals who could not read or write but found someone to write petitions for them.

Those who were not literate sought out people who could write on their behalf. They frequently turned to friends or asked members of groups like the confraternities, the militias, or the African “nations.” In the case of the militias, most captains were literate. They could read, or at least write in some capacity. Molina was a lieutenant of a free black militia and he recounts that the inspector general for the militias actually asked him to teach some of his fellow militiamen how to read. It is remarkable that a white professional military officer told a free black man in the 1790s to teach fellow black militiamen to read. That rung all the wrong bells for the colonial regime.

[Molina’s life] is a very contradictory story full of what historian Leo Spitzer called “the predicament of marginality,” the condition of people from subaltern classes who try to appropriate all of the trappings of the dominant culture, but still face new forms of marginalization despite their efforts. Molina was a loyalist and a staunch defender of Spanish colonialism. That’s probably how he became very close with some of the white elites in Montevideo who were also defenders of Spanish colonialism. Perhaps these very conservative white elites in Montevideo saw in Molina something that they shared, like the nostalgia for the old colonial regime. However, even in that setting, Molina tried to forge new places for Africans and their descendants. I found him writing for other people, being a ghostwriter for free black people defending themselves or trying to get freedom for their enslaved wives. In that way, he embodied the “predicament of marginality,” trying to go beyond what was expected for him as a black man in Montevideo and being very proud of his investment in European written culture.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Far above average!