Envisioning Black Memphis at Midcentury

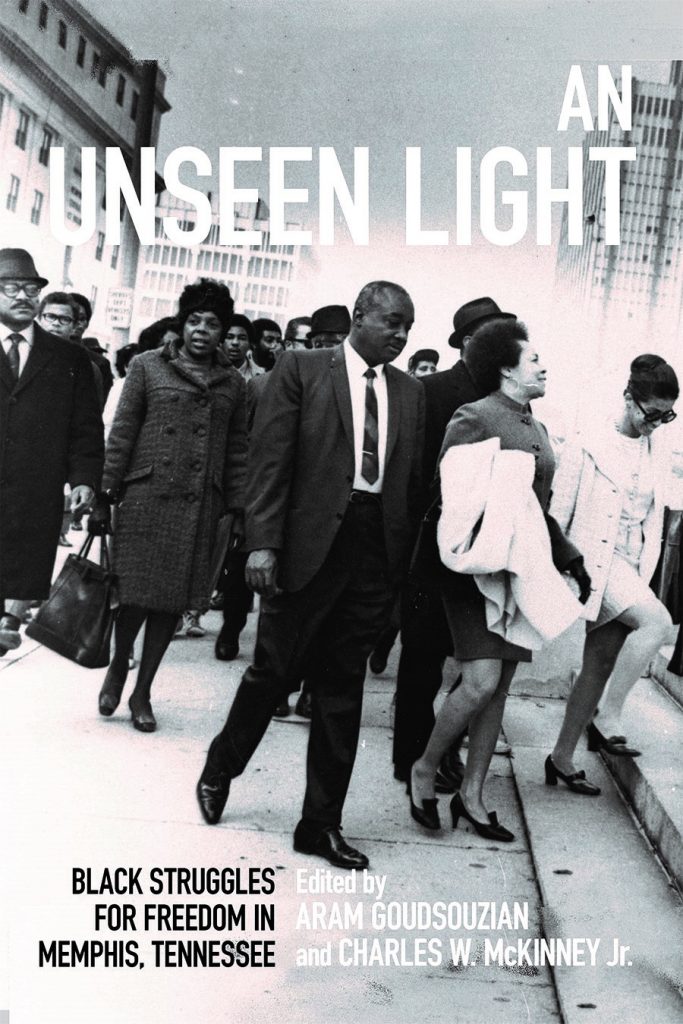

*This post is part of our online forum on Aram Goudsouzian and Charles McKinney’s An Unseen Light

By 1940, Memphis, Tennessee was – with a population of over 300,000 – the south’s seventh largest city. The city’s character was shaped by thousands of Black and white migrants who had come to the city from rural areas in western Tennessee, northern Mississippi, and eastern Arkansas. Forty percent of the city’s population was African American, a percentage that had grown from sixteen percent in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, fallen off during yellow fever epidemics and other crises, and expanded with the steady migration of Blacks and whites. Although they interacted in public spaces, Black and white Memphians were legally and customarily segregated from the cradle to the grave. They lived in separate neighborhoods, attended separate schools and churches, created and supported separate businesses and professionals, and were buried in separate cemeteries.

Statutes and imagery commemorating a “Lost Cause” interpretation of the southern past peppered the city’s physical and visual landscape. In 1905, an equestrian monument to Nathan Bedford Forrest – Confederate general, antebellum slave trader, and Klansmen – was erected in a public park. Three years later, Confederate Park, on the bluffs above the Mississippi River, was dedicated as a “memorial to the Civil War.” But there were no memorials or monuments to the men of the United States Colored Troops who had manned the Union Army’s Fort Pickering, constructed after a Union naval victory on the Mississippi River restored federal control of the city.

In the first half of the twentieth century, most white Memphians supported the erection of monuments and memorials to their interpretation of the southern past. In Memphis, as in other communities, stereotypical images of Black women and men supported these southern memories. Central to these memories was the image of the “Mammy.” In 1920, Fannie E. Selph presented a paper on “The Black Mammy of the Old South” to a Nashville chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Selph described a “faithful black mammy named Aggie” who served in the household of Colonel Thomas Kennedy Gordon in Giles County, Tennessee. Aggie raised the Gordon children after Mrs. Gordon’s death and had the respect of the whole household. When the Union Army raided in the vicinity of the Gordon household, Aggie personally guarded the family silverware and other valuables. After emancipation, she chose to remain as “one of the (Gordon) family,” who constructed a room for Aggy in the yard. When she died, she was dressed “in one of ole Miss’ dresses. . . her body . . . allowed to lie in the parlor” before burial in the family’s cemetery plot. All of this was done as Aggie, the faithful “mammy,” had requested.

In 1923, the same year that the U.S. Senate authorized a statue “in memory of the faithful slave mammies of the South,” a July 23rd issue of Memphis’s Commercial Appeal published a cartoon of “Mammy” serving watermelon to her husband or son at a table balanced on top of a world of cotton bales. The accompanying anti-migration article attempted to convince African Americans that they were much better off in the south, where they enjoyed unlimited job opportunities, good wages, and abundant food, than confronting the uncertainties of the north.

“Mammy” was also used to promote the city’s Cotton Carnival, a celebration of the importance of cotton to the local economy. Black women dressed as Old South “mammies” were depicted in “plantation tableaus” caring for white children, telling fortunes, or washing clothes. As historian Cynthia Sadler noted, “the most popular image of black womanhood (among white southerners) was that of ‘Mammy,’ whose subservient yet nurturing presence added atmosphere to carnival events.” Black women, dressed in Mammy costumes, were hired to sit on cotton bales on downtown streets and instructed to “conduct themselves in keeping with the traditions of the old mammies” who were “highly regarded characters of the South.” Black men were hired to pull parade floats or carry the white royalty on special litters to their thrones.

Memphis businesses used “Mammy” to advertise products. In 1942, the White Rose Laundry erected an electrical sign depicting an overweight washerwoman bending over a washtub happily scrubbing clothes. The laundry’s owners dismissed complaints from the Memphis Negro Chamber of Commerce that the sign was “ a complete effrontery for Negro people,” “a subtle although effective ridicule of the race,” and an “effort to embarrass Negro citizens of Memphis” by asserting that “We are entirely at [a] loss to understand the cause of any resentment by anybody as certainly no discredit to the negro race was intended. The figure represents the kindly old negro mammy who is loved by people of both races.”

With these stereotypical images of African Americans and the monuments and parks commemorating the Lost Cause, white Memphians envisioned a twentieth century city still influenced by nineteenth century ideologies of race. Yet Black Memphians had been reshaping the city’s racial dynamics since the Civil War. G.P. Hamilton’s 1906 directory The Bright Side of Memphis, newspapers like Ida B. Wells’s Free Speech and Headlight (published in the late 1800s), The Memphis World, and The Tri-State Defender (both published in the mid-1900s), as well as the work of Black photographers like the Hooks brothers (Henry and Robert), Ernest Withers, and L.O. Taylor depicted a different Black Memphis. While the work of the Hooks brothers and Withers was well known for much of the twentieth century, L. O. Taylor, a self-taught photographer, was most familiar to Black Memphians as one of the city’s leading Baptist ministers.

From the mid-1920s through the 1960s, L. O. Taylor pastored at least four Memphis churches and trained countless young men in the art of preaching. Taylor had a gift for interpreting the scriptures in ways that his listeners easily understood and applied to their daily lives, and people flocked to hear him preach because he spoke their “lingo.” James Netters, who grew up in Olivet Baptist Church when Taylor was minister and was later licensed to preach by Taylor, remembered the “real sincere way” Taylor handled people. For Taylor, “church” was not just the site of the Sunday morning religious service; it was the physical, social, and emotional center of the community. In a city like Memphis, with a large population of rural migrants, “church” was where country folk brought their old-time religion into an urban setting. But as Taylor ministered to his congregation, he also documented the neighborhood around him. Taylor was a self-taught photographer and videographer, who used his camera lens to capture Black men, women, and children at work, at play, in schools and churches, in restaurants and businesses. His photographs depicted the lifestyles of real Black Memphians, not uncomfortable caricatures of Lost Cause ideology.

While the Hooks brothers and other Black photographers worked from downtown studios or traveled around the city, state, and nation chronicling the growing civil rights activism of the second half of the twentieth century, Taylor made portraits in a small improvised home studio. Or, he took his equipment to other churches, schools, or the homes of his clients. Taylor filmed congregations parading in silent, orderly precessions out of churches, travelers arriving at National Baptist Conventions, students at a local business college, and a baptism in a local creek.

Like many Black ministers in the first half of the twentieth century, Taylor was a social and political conservative who accommodated to the machine politics of E.H. Crump. These ministers “lagged behind black businessmen and professionals in supporting labor unionism and civil rights, and rarely challenged the status quo in the city’s race relations.” But Taylor voted and supported the neighborhood civic club. Local ministers who knew him could not remember him being involved in civil rights activism, but Reverend P. L. Johnson recalled, although

I don’t think I ever met him at a civil rights movement [but what] he was doing was just as good or better. . . What he was doing [photographing and recording] was important . . . [And] there was nobody else doing it so why should he leave that and go to the civil rights movement? Cause . . . everybody was doing the Civil Rights movement.

Historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham has also suggested that Black ministers created institutions (churches) that provided sites of “psychological resistance” and “interstitial space in which to critique and contest white America’s domination.” Taylor’s churches and his photographic studio served these functions. Perhaps he did not show much interest in politics because, as a close friend noted, he “thought a minister’s job was what God gave him to do.” He encouraged his congregations “to vote and ‘vote right’”; to vote for what was best for the race. By depicting the ordinariness of Black life, Taylor challenged caricatured images of Black men and women and created a strong, confident community base on which activist ministers could build movements.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.