Enslaved People and Divorce in the African Diaspora

Numerous books and articles analyze the concept of “slave marriage,” but other than a few exceptional works, the historical literature severely lacks analyses of slave divorce. This current state is understandable for a few reasons. First, most slave testimonies discuss the contours of marriage under slavery but rarely mention divorce procedures. If slaves ever separated, it was a forced split caused by the master’s interference. Former slaves naturally preferred to disclose how enslaved people fought for marital dignity to critique the hypocrisy of “Christian” slaveholders who severed their marriages. Admitting that enslaved people willingly separated from one another potentially damaged the abolitionist cause, as it could fuel the perception among racist whites that people of African descent did not respect the bonds of Eurocentric matrimony. Secondly, the cultural turn among scholars of slavery in the 1970s and 1980s contested past histories that rendered slaves docile and cultureless, preferring to view the familial unit through the vantage point of resistance, and some scholars asserted that enslaved people, against all the odds, formed solid and supportive domestic structures despite the slaveholder’s encroachments. The narrative of resistance proved immensely popular, and some viewed the slave family as a unit fostering psychological survival.

Though recent histories of slavery and capitalism caution historians against romanticizing the durability of slave communities, often citing the “domestic slave trade” as an example of Black people possessing no agency in experiencing familial separation, the narrative of resistance remains popular for those seeking to reclaim slaves’ human dignity. After all, the violence associated with forced separations, as frequently happened in the antebellum South, would surely encourage one to maintain their domestic structure and all available systems of support. But viewing the enslaved through this limited lens is a disservice toward understanding the emotional histories of those trapped in bondage. Like any other group, enslaved people acted upon their feelings and passions. Willingly severing the marital tie was one way to express dissatisfaction with a partner and dictate the terms of enslaved people’s relationships.

Divorce was undoubtedly not a new concept in the diaspora, as precedents existed throughout Atlantic Africa. Most Atlantic African societies were governed by a set of rules when severing marital relationships, which often favored the woman. If a wife was a victim of domestic violence, for instance, she could flee her abuser and initiate a separation from him. Couples severed the marriage by a unique method of courtship applied throughout much of Atlantic Africa, in which the man delivered gifts to the woman’s family when requesting her hand in marriage. Often called a “bridewealth,” the bride’s parents retained the value of the husband’s original gift in case the partners were dissatisfied with each other. If the woman decided to separate from her spouse, she returned to her family, and the wife or her family reimbursed the husband the value of his gifts. This process ended the marriage.

Such circumstances were difficult to replicate under slavery, but one source from colonial North Carolina reveals that some slaves attempted to replicate this process in the diaspora. In 1731 a traveler named John Brickell observed a marital ceremony among two slaves, in which the suitor presented his potential wife with a small gift. They were only married if she accepted his token. Brickell made one brief reference to the divorce proceedings, unintentionally providing a window for understanding how colonial slaves conceptualized their marital relations as diasporic Africans: “if ever they part from each other . . . upon any little Disgust, she returns his Present.” Though the circumstances of slavery rendered slight alterations to the process (i.e., parental approval was absent), this divorce ritual bears a striking resemblance to those used by Atlantic Africans. It appears that enslaved people tried to retain those ancestral customs that best served their domestic attachments.

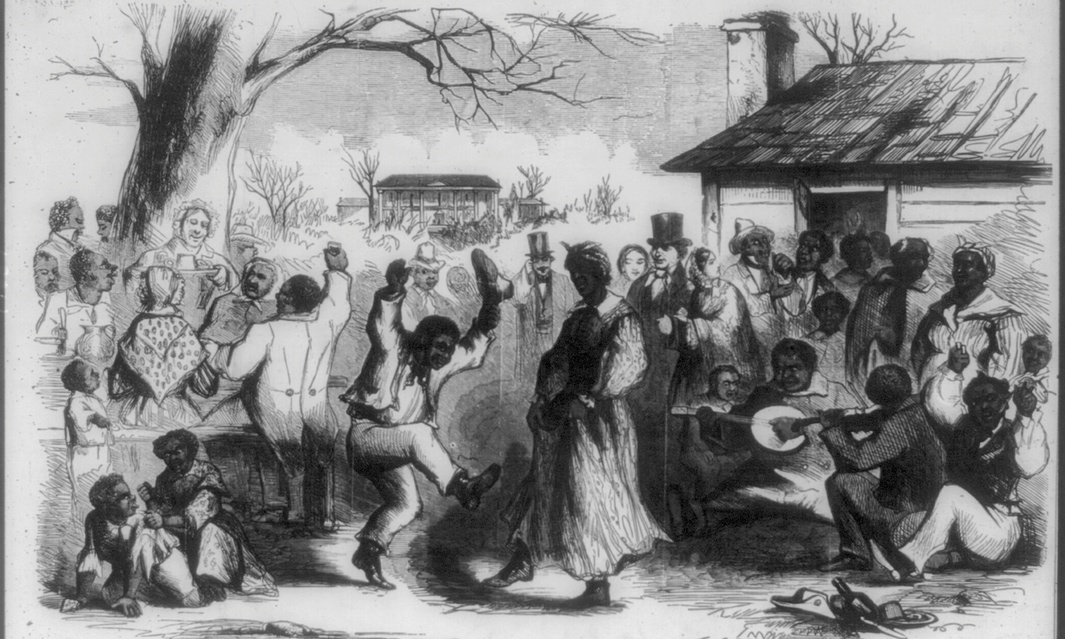

As slaves entered the antebellum period (1800-1860), however, Atlantic African retentions faded in many areas. But upon adopting European traditions, some of these newly acquired ceremonies fit enslaved Africans matrimonial needs. The broomstick wedding, in which newlyweds hopped over a broomstick to declare themselves man and wife, provided this approach to divorce. According to Cora Armstrong, formerly enslaved in Arkansas, couples in her community “jumped over the broom and when they separated they jumped backward over the broom.” Though she provides few details surrounding couples’ motivations to separate, her testimonial resembles a similar ceremony practiced by the Welsh in the United Kingdom. According to oral histories collected by folklorist W. Rhys Jones, one community in Northern Wales jumped the broom “in the presence of witnesses,” and by simply “jumping backwards . . . the marriage was broken.”1 Though the ceremony lacked the pomp and display of elite Christian weddings, it reveals how marginalized people still believed that if a ceremony recognized their marriage, then divorce should also contain a ritual process.

But how did divorces feel for those trapped in chattel slavery? One can certainly imagine enslaved people felt a broad swathe of emotions, ranging from grief to happiness, and even relief. As with any separation, the circumstances in each case were unique, and such details determined how each partner reacted. Some enslaved couples did not mutually agree to divorce, but one partner simply deserted the other. Occasionally, this was done without the spouse’s knowledge, and it was exceptionally effortless if they were in an “abroad marriage,” a term used to describe married couples who lived on separate plantations. One source reveals the emotional trauma the abandoned partner experienced in this type of separation. In a letter written through her mistress, a Virginia slave named Betty inquired about her abroad husband John Morloe who she believed was allowing Rose Burvel, another woman from his plantation, to do his “washing, & it seems that her mother and father are trying to get John to marry her.”2 Betty demanded this relationship cease, and asked John’s master, Dr. Perkins, to encourage John to visit her the following weekend, as she had not seen him for two months since she gave birth to their twins. This single letter is the only context we have surrounding John and Betty’s domestic complications, making it nearly impossible to fully understand their circumstances. However the given information suggests that John chose to abandon his first wife and his new responsibilities as a father, even though Betty still desired his company. John remains silent in the record, but Betty’s psychology is vividly displayed.

At times it was merely a conscious choice among spouses whose differences were irreconcilable. Asked by an interviewer if she was widowed before marrying her current husband, one enslaved woman responded, “He isn’t dead . . . he’s livin’ yet. I didn’t like him, and I neber did; so I tuk up wid my ole man . . . I’se a great deal younger dan he is, but I wouldn’t change agin.” One can extract some compelling points from this brief statement. The woman does not disclose why she married her first husband, though it is possible that either the union was a forced marriage or the options available to her in the area were few. Her conscientious choice to separate herself from an unhealthy first marriage reveals the complexity of the slave’s private sphere, in that love and romance could be fluid experiences that were subject to the same emotional and physical complications as those married in freedom. Despite the possibility that her first husband may have been closer to her age, she found happiness and stability with her second husband. Those feelings were sufficient in justifying her reasons for divorcing her first partner.

Studying slaves’ domestic realities continues the “project of deromanticization” brought forth by historians like Jeff Forret, whose work, Slave Against Slave: Plantation Violence in the Old South, pushes against the narrative of a unified slave “community” united against slave owners. Through an exhaustive study of primary sources, Forret unveils episodes of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse slaves committed against one another. Slave Against Slave does not discount the systemic, interracial violence rampant throughout the Old South, but argues that instances of intraracial violence help scholars understand enslaved people as human beings. To properly contextualize historical figures, we should resist portraying them in versions of how we want them to be, and we must try and understand that they engaged in and were the subjects of passionate outbursts that harmed those around them, even those they loved. Similarly, to accurately reveal how enslaved people viewed their romantic attachments we must examine how and why they willingly separated from one another.

Dr. Parry,

This is wonderful! I am a psychologist interested in and witness to the impact of separation and divorce on the children I see as clients. Your work has deepened my understanding of the historical context of marriage and divorce among our people.

Your references also guided me to explore and take a deeper dive into the day to day lives of our enslaved ancestors.

Best wishes!

Andrea Francis, PhD.

Thanks so much for the kind words, Dr. Francis! Your comment means the world to me. It has been quite a journey uncovering the private lives of the enslaved, and I am so glad people find my writings of some benefit in understanding them further.

Best Regards,

Tyler D. Parry