Ebony Magazine, Black Baseball and Identity in America

Baseball’s Opening Day offers an opportunity to once again consider the relationship between America’s pastime and Black thought in American history. Ebony magazine long held itself up as a forum for Black America, and this was especially true of the importance of baseball to Black America. For decades, Ebony ran an “Annual Black Baseball Roundup,” featuring all the Black players in Major League Baseball. Yet, as Black American interest in baseball waned, even Ebony sat up and took notice. “Sixty years after Jackie Robinson integrated the sport,” writer Yusuf Davis posed, “the issue of Blacks in baseball remains a deeply rooted complexity discussed in boardrooms and barber shops, with no shortage of theories and remedies.” If we take seriously Ebony’s role in creating and debating Black American culture, than the standing of baseball in the magazine mirrors the rise and fall of baseball as a Black American tradition.

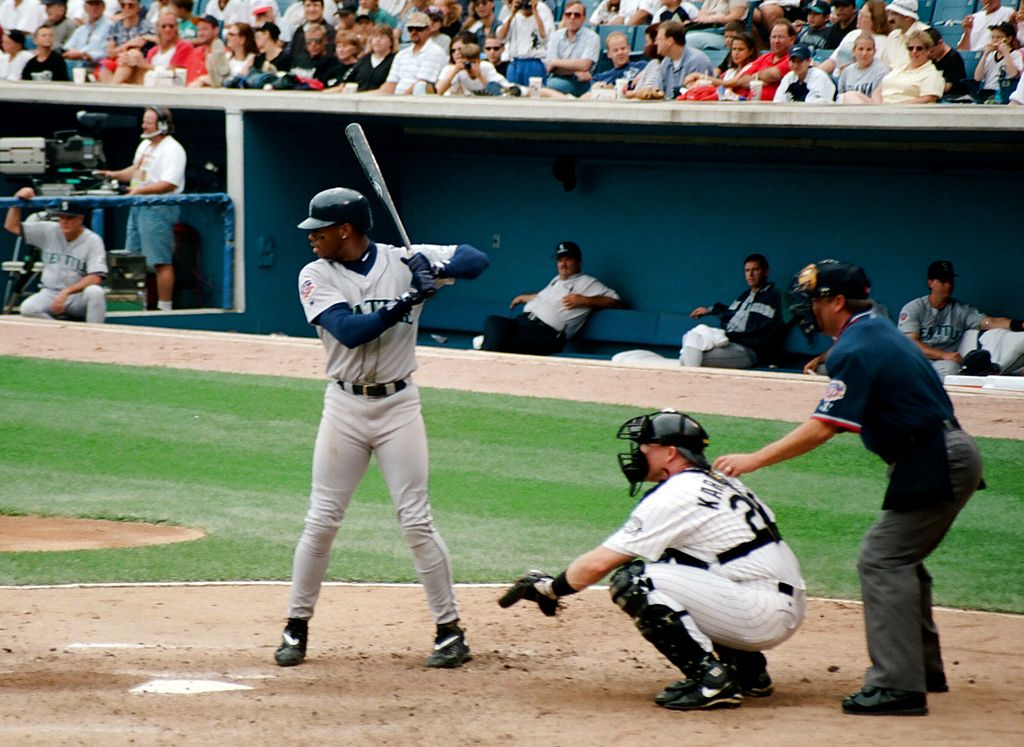

Ebony magazine’s annual round-up of Black American ball players was, for my younger self in the 1990s, one of the best parts of the magazine’s year-round publishing. Produced every June, as the Major League Baseball season entered the “dog days of summer,” it offered Black baseball fans a chance to see who played for every team in the Majors. Perusing the section year to year offers a snapshot of Black baseball, from the glory days of Willie Mays and Hank Aaron, to the generational talents of Ken Griffey, Jr. and Barry Bonds. But the Black baseball section offers more to historians and sports fans alike than a trip down memory lane. For fans of the game, it should be a reminder of how important baseball once was among Black Americans. For historians, it is also a reminder of how sporting culture was never far from, say, the intellectual and cultural debates taking place among Americans throughout the twentieth century.

Take, for example, the June 1960 issue of Ebony, the earliest version of this annual roundup I could find on the Ebony archive on Google Books. If a young Black fan of the game flipped through the pages to eagerly devour the annual baseball roundup, they would have noticed an essay about the growing sit-in movement by Lerone Bennett, Jr. Reflecting on the wave of sit-ins that began in Greensboro, North Carolina when college students from North Carolina A&T—an all-Black institution—sat at the Woolworth’s lunch counter, Bennett wrote, “In a great upswelling of moral indignation, church groups, politicians and public figures climbed on the sit-in bandwagon.” Perhaps the baseball fan reading Ebony to learn more about the exploits of Maury Wills or Ernie Banks paused for a second, thinking about how he or she could contribute to the sit-in protests stunning the nation.

Or take the case of Curt Flood. His battle against baseball’s reserve clause—which prevented players from choosing for themselves which teams they could play for—divided fans in 1970. But Ebony saw Flood’s fight as part of a larger struggle for Black people to control their labor power, whether it was on the playing field or in the streets. Calling him “baseball’s long-needed ‘Abe Lincoln’” Flood was celebrated in the pages of Ebony for standing up against this labor system. “It will be a bit of poetic justice,” the editors of Ebony noted, “should it turn out that a black man finally brings freedom and democracy to baseball. After all, organized baseball kept black players out of the game for 75 years because they were black.”

Questions of race, labor, and citizenship underlie the fun and games of the annual Black baseball roundup. But identity—in this case, who counts as Black in America—also comes up from time to time in the special sections. A letter to Ebony magazine pointed out how the magazine’s run-down, at times, did not include Afro-Latino players. “You are not living up to your name,” the letter from Florentina Flores Martinez begins. “I am a Black Latino,” he continued, “and I found your ‘collection’ incomplete, to say the least.” Another letter, from Mario Root, also made clear their displeasure with erasure of the larger Black diaspora. “Regardless of whether the brothers from Latin countries consider themselves African,” Root wrote, “you don’t have to fall into this obvious trap of divide and conquer.” As much as the game of baseball serves as an arena for debates about American patriotism and identity, it is important to note how it can also serve as a platform to talk about internal debates among Black Americans about the definitions of “Blackness.”

This brings us back to the 2007 essay on the decline of Black participation in baseball. The Ebony essay included the argument that some made, that Black Americans in Major League Baseball had simply been replaced “with Black and Brown faces from Latin America and Asia.” In addition, arguments about the decline of Black American participation in the nation’s pastime sound like the traditional arguments about the decline of Black families and Black culture in a post-Moynihan Report world. Arguments that the lack of male-run households contribute to a lack of Black ballplayers later on are included among a number of reasons—including some financial—explaining the slow but steady demise of the Black American baseball player.

Historian Lou Moore, in a 2021 essay for Global Sport Matters, pointed out that more could have been done by MLB to stop this decline—but simply was not. Moore noted that Black players and scouts alike warned officials in MLB that there was an inevitable drain of Black talent away from the game in the 1970s. “Yesterday’s icons warned us this day was coming,” Moore wrote. “But the league never righted the ship.” Lack of resources for some HBCUs to field baseball teams; a small number of college scholarships to offer prospective players; and the high cost of fielding a Little League team in an economically disadvantaged area; all of these reasons, noted Moore, further hurt the numbers of Black American baseball players. One cannot help but note these arguments coinciding with debates about the decline in Black Power and uncertainty about Black economic and political strength during the 1970s.

The story of Black baseball in the United States is a broader story of Black life in the United States. Questions of economics, identity, and politics are always with us, even when it comes to the simple game of baseball. Ebony magazine long recognized this, and within its pages, the story of baseball in America became a story of Black achievement, Black identity, and later, unfortunately, a story of Black retreat from the game. Whether this changes in the future is unclear, but the importance of sport to Black intellectual life in America is not.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.