Documenting Nannie Helen Burroughs: A New Book About a Pioneering Civil Rights Leader

This post is part of our blog series that announces the publication of selected new books in African American History and African Diaspora Studies. Nannie Helen Burroughs: A Documentary Portrait of an Early Civil Rights Pioneer, 1900-1959 was recently published by Notre Dame Press.

***

Editor of Nannie Helen Burroughs: A Documentary Portrait of an Early Civil Rights Pioneer, 1900-1959 is Kelisha Graves, an Instructor and Honors Program Adviser at Fayetteville State University. She is a doctoral student in Educational Leadership with a concentration in Higher Education. An interdisciplinary scholar, her research interests span Educational Leadership, Philosophy, and Africana Studies. Her research interests specifically include African American intellectual history, African American philosophy, educational leadership and administration, philosophy of education, curriculum planning/development, innovative ways to use technology to improve teaching and learning in the classroom, socio-cultural knowledge(s), and critical race theory. In the field of education, Graves’s work focuses on maximizing learning for underserved students through transformational pedagogies. Her goal is to inspire intrinsic motivation in students through autonomy-supportive teaching and learning strategies. She is committed to exploring unconventional intellectual journeys that lead to deeply valuable outcomes. In the field of intellectual history and philosophy, Graves’s work turns an eye toward the development and conceptual genealogy of African American thought from the nineteenth century to the present. Graves has authored/co-authored works in the fields of education, African American history, and Black philosophy. Follow her on Twitter @KelishaGraves.

Editor of Nannie Helen Burroughs: A Documentary Portrait of an Early Civil Rights Pioneer, 1900-1959 is Kelisha Graves, an Instructor and Honors Program Adviser at Fayetteville State University. She is a doctoral student in Educational Leadership with a concentration in Higher Education. An interdisciplinary scholar, her research interests span Educational Leadership, Philosophy, and Africana Studies. Her research interests specifically include African American intellectual history, African American philosophy, educational leadership and administration, philosophy of education, curriculum planning/development, innovative ways to use technology to improve teaching and learning in the classroom, socio-cultural knowledge(s), and critical race theory. In the field of education, Graves’s work focuses on maximizing learning for underserved students through transformational pedagogies. Her goal is to inspire intrinsic motivation in students through autonomy-supportive teaching and learning strategies. She is committed to exploring unconventional intellectual journeys that lead to deeply valuable outcomes. In the field of intellectual history and philosophy, Graves’s work turns an eye toward the development and conceptual genealogy of African American thought from the nineteenth century to the present. Graves has authored/co-authored works in the fields of education, African American history, and Black philosophy. Follow her on Twitter @KelishaGraves.

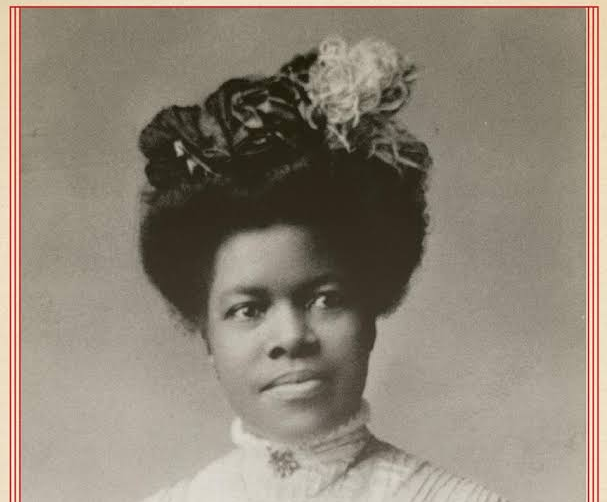

Nannie Helen Burroughs (1879–1961) is just one of the many African American intellectuals whose work has been long excluded from the literary canon. In her time, Burroughs was a celebrated African American (or, in her era, a “race woman”) female activist, educator, and intellectual. This book represents a landmark contribution to the African American intellectual historical project by allowing readers to experience Burroughs in her own words. This anthology of her works written between 1900 and 1959 encapsulates Burroughs’s work as a theologian, philosopher, activist, educator, intellectual, and evangelist, as well as the myriad of ways that her career resisted definition. Burroughs rubbed elbows with such African American historical icons as W. E. B. DuBois, Booker T. Washington, Anna Julia Cooper, Mary Church Terrell, and Mary McLeod Bethune, and these interactions represent much of the existing, easily available literature on Burroughs’s life. This book aims to spark a conversation surrounding Burroughs’s life and work by making available her own tracts on God, sin, the intersections of church and society, Black womanhood, education, and social justice. Moreover, the volume is an important piece of the growing movement toward excavating African American intellectual and philosophical thought and reformulating the literary canon to bring a diverse array of voices to the table.

As Kelisha Graves posits, most of the existing black women’s historical, intellectual, and religious scholarship offers limited insight (if any) into the views and ideas of Nannie Helen Burroughs, despite her views and published writings on wide-ranging, important topics from democracy and human rights to gender and social justice. The issues, organizations, and movements in which she was personally involved as an activist and thinker were not only significant during her lifetime: they still have compelling contemporary resonance. This volume offers the first compilation of Burroughs’s scattered writings in a single text, ensuring them a more central role in future historical feminist, religious, and social justice narratives. —Sharon Harley, University of Maryland

J.T. Roane: What type of impact do you hope your work has on the existing literature on this subject? Where do you think the field is headed and why?

Kelisha Graves: The impact I hope this work has on the existing literature is multifold. I hope this book serves to expand the literature on Nannie Helen Burroughs by providing a volume that represents a repository of some of her most critical writings and speeches. Burroughs’s lack of mention in much of the conversation on early-twentieth-century race thought did not make sense to me in view of both the popularity she experienced during her lifetime and the massive volume of intellectual material she produced. This project emerged from the belief that Burroughs needed to be located firmly in the canon of twentieth-century race thought. While Burroughs is primarily known for her career as a school-builder, what is less known is her importance and impact as a thinker, writer, and philosopher. She was a key contributor to twentieth-century discourses surrounding topics of race, social justice, religion, and cultural philosophy. Burroughs deserves to be taken with the same frequency and fervor as we see with Anna Julia Cooper and others. Many of the current and previous works on Burroughs are biographical in nature, and this is important for understanding where she lands as a historical figure. However, I hope this work encourages an engagement with Burroughs in terms of her philosophy and thought. Her writings reveal a woman who lands among and wrestles with thinkers like Du Bois, Garvey, Washington, Woodson, and others. Towards a broader point, I hope this work thickens the intellectual traffic between Black philosophy and Black intellectual history by highlighting how Burroughs embodied both traditions in her work.

I envision this project as a contribution to the growing literature on Black women’s intellectual thought. Current trends in the field demonstrate that scholars are exemplifying what I call archival-archaeological prowess by excavating from obscurity and neglect the names and intellectual productions of heretofore unheralded Black thinkers. The field is headed toward highlighting the unsung Black women thought-leaders whose voices help us to identify the departures, convergences, and cross-pollination of ideas that make up the expanding and diversifying ecosystem of Black intellectual thought. Furthermore, in view of our devotion to Black Girl Magic, there is an urgency to name and identify the foremothers whose intellectualism enabled our collective progress. Nannie Helen Burroughs, founder of the National Training School for (Black) Women and Girls, represents such a foremother.

Another piece of history gone completely unnoticed, thank you for bringing her to light!