David Walker and the Problem of American Consensus

There are many different ways to teach the historical development of African American political history. One way is in the service of the post-racial fallacy. An alternative way highlights those instances where activism has arisen less from a view of a better future and more from an impassioned insistence that the rooted problems of the past and present demand immediate response.

Whether one had or continues to have post-racial dreams, many very astute writers have revealed the problematic ideological premises behind post-racial dreaming. Worse than being vague, this conceptualization suggests that Americans should emphasize their common humanity by working simply to forget and somehow compartmentalize continuing patterns of systemic violence and intentional oppression.

Rather than question how the idea of the post-racial functions, one might still hold out hope for its possible future arrival. Yet, Ta-Nehisi Coates concisely explained that the ideological foundations for believing in the possibility of a future post-racial society can actually undermine the kind of activity necessary for working towards a post-racist society.

Among the many important origins of the post-racial idea, two sources deserve emphasis. First, the idea of a post-racial society assumes that history moves in a linear and progressive pattern that is always ultimately impelled by consensus. African American political thought provides numerous examples of investment in consensus, or the belief that the ending of racism in America could arise out of processes that would cohere rather than split state bureaucracies and nationalist enthusiasm. Certainly, the idea of consensus as the main explanatory narrative of American history arises from an array of historical, theological, and political sources.

Second, the idea of a post-racial society reflects the belief that when certain thresholds of political justice and equality have been exceeded, certain forms of political work will no longer be necessary. Ironically, the conditions that have produced the description of society as being post-racial actually represent an environment where racial gains can always easily and dramatically become racial losses. Imagining a post-racial society implies an inchoate belief that politics will tend towards stability and compromise.

Black political thought is well represented by those figures who have argued for transformation and who have renounced consensus as a guiding principle for political action. These thinkers have wondered, if not directly questioned, whether ending racism might actually entail the dismantling of the state.

David Walker, a nineteenth-century abolitionist, provides a classic example. Walker argued that structures of power had to be confronted without the pressure that consensus should be a necessary determinant of how confrontation should proceed. For Walker, any emphasis on consensus obscured the pressing problems of fomenting and organizing political activism.

In the third edition of his famous Appeal, David Walker warned, “I tell you Americans! that unless you speedily alter your course, you and your Country are gone!!!!!!!! For God Almighty will tear up the very face of the earth!!!” Walker further explained,

This language, perhaps is too harsh for the American’s delicate ears. But Oh Americans! Americans!! I warn you in the name of the Lord, (whether you will hear, or forbear,) to repent and reform, or you are ruined!!!

Channeling a stern God of the Hebrew Bible who unforgivingly dispensed justice, Walker’s politics were animated by an imagined future of justified violence against slavery. Rather than focus on a future post-racial society, Walker emphasized the violent reckoning that had to happen by way of direct and perhaps even violent response to American racism. From Walker’s perspective, this was a racism that included hypocritical white Christian slaveowners and even blacks, “many of my brethren.”

Walker chose to address the immediate and pervasive problems of racism, although he would have had reason to highlight progress. Walker published the first edition of his Appeal in 1829, almost fifty years after the end of the American Revolution. Walker knew that most New England states had abolished slavery. Walker, himself, was an active member in several black institutions that had arisen from northern emancipation, including Boston’s African American Masonic Lodge. Walker certainly knew of the Gradual Emancipation Acts that were passed by Pennsylvania (1780) and were then followed by similar legislation in Connecticut (1784), Rhode Island (1784), New York (1799), and New Jersey (1804). Walker served as a Boston agent for the first black newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, founded in 1827.

Despite all of these advances for northern African Americans, Walker did not declare the coming of a new age of freedom and equality and he would not confirm the U.S. as a promising experiment in union and democracy. Certainly, Walker recognized that the United States was a young nation. Yet, his providential outlook did not envision a society that sat beyond a past of slavery and racist prejudice. Walker highlighted the deeply rooted nature of racist prejudice and he connected this directly to the institutions of the United States. The problematic idea of a Christian and masculine respectability shaped Walker’s view that slaves should rise against their masters, yet by framing slavery as a problem of history and politics, Walker highlighted the importance of conflict, and not pragmatic compromise, as the animating factor in political effort.

Walker emphasized transformation and he directly challenged the idea of peaceful change. He did mean to inflame as much as he meant to explain the difficulty of altering society. A newly free north could have provided Walker evidence to emphasize the possibility of eventual racial reconciliation. Instead, Walker insisted that the tenacity of slavery and the pervasiveness of racism reflected enduring problems of national ideology. These problems would not somehow sink away under their own immoral weight.

Scholars have debunked the historical idea that slavery began to disappear during the American Revolution mostly because slavery’s wrongfulness became self-evident. Certainly ideas mattered in the first phase of slavery’s abolition. Yet, almost fifty years after the colonial rebellion, Walker did not believe that simply bellowing first principles of human equality would convince most whites to end slavery or see blacks as equal.

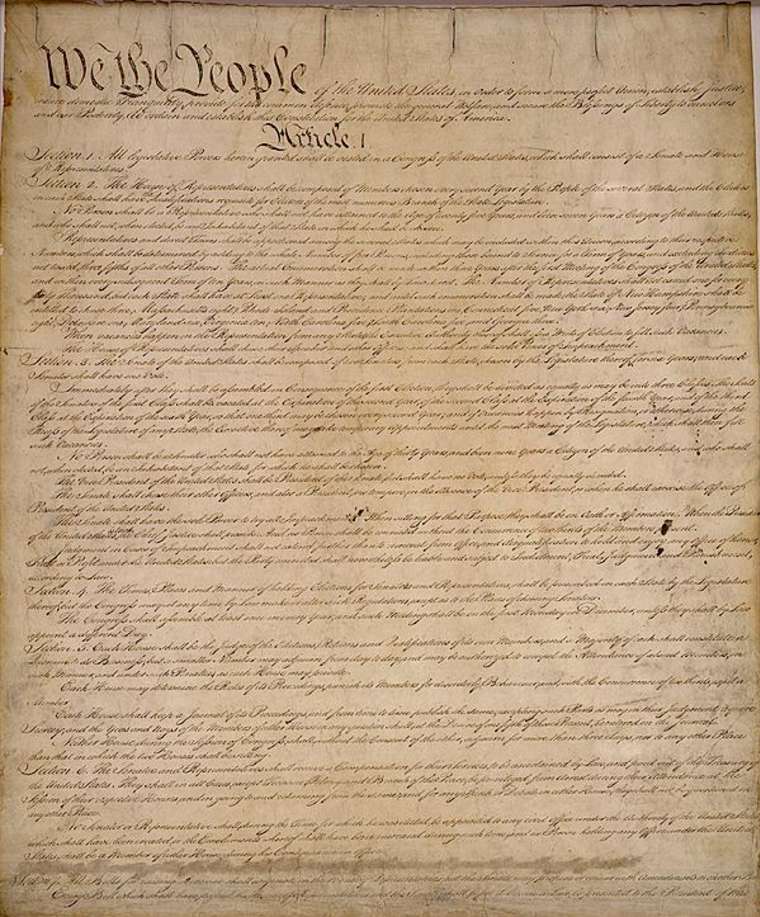

Before concluding the third edition of his address with a hymn from the Psalms of David, Walker quoted the Declaration of Independence. He meant to demonstrate the right of African Americans to take freedom in direct fashion rather than argue that they deserved it. He repeated to America its own language of rebellion:

Hear your language further! ‘But when a long train of abuses and usurpation, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security.

Now that we have entered the month of February, the American public will no doubt be presented with a particular historical Martin Luther King, Jr., a person who dreamed that racism would fall away against the soft edge of national consensus. Yet, the American public will have to dig a bit to find a particular Martin Luther King, Jr. who questioned America’s colonial project in Vietnam, who demanded that America take in those refugees who were victims of America’s own violence overseas, who questioned the state’s commitment to economic justice, and who grew increasingly impatient, if not disillusioned, with the idea of consensus as an animating feature of civil rights activism. The American public will have to dig much, much deeper to hear the words of Walker, who framed his hope for the future in terms of a prophetic nightmare rather than a dream of solace. Today we should hear the echo of his Appeal; we should not make activism subservient to compromise.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.