Culture Warriors: Ishmael Reed’s Japanese by Spring and Afro-Asian Critique

**This is the fifth installment of my series on Afro-Asia, examining the cultural and political exchanges and historical connections between people of African and of Asian descent. This month, I invited Dr. Lavelle Porter to share some of his research on the topic. Dr. Porter was born and raised in Meridian, Mississippi and graduated from Morehouse College with a B.A. in History in 2000. He holds a Ph.D. in English from The CUNY Graduate Center where he completed a dissertation titled The Over-Education of the Negro: Academic Novels, Higher Education and the Black Intellectual. He has taught courses on African-American Poetry, contemporary American fiction, early American literature, and New York City history. He is currently working on a book about academic fiction and black higher education. In Fall 2015 he will be an Assistant Professor of English at the New York City College of Technology.

**

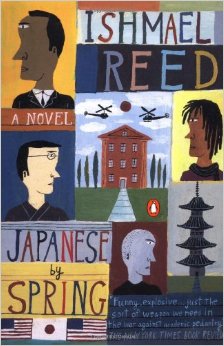

Recently, Duke University professor Jerry Hough blessed an Internet message board with his Harold and Kumar-level of analysis on the comparative assimilation strategies of Asian-Americans and African-Americans. As he stated, “Every Asian student has a very simple old American first name that symbolizes their desire for integration. Virtually every black has a strange new name that symbolizes their lack of desire for integration.” Hough’s crude comments are part of a long history of white supremacy’s construction of blacks and Asians as politically oppositional (and complementary) groups, and they sit squarely within a history of black-Asian encounters globally and in the United States. I couldn’t help but think of Ishmael Reed’s satirical academic novel Japanese by Spring, and this seems like an opportune moment to revisit Reed’s caustic academic satire of the Culture Wars.

In Japanese by Spring, an academic novel about a conservative black literature professor at a California college in the early 1990s, Ishmael Reed satirizes the period of intellectual debates in the 1980s and 1990s commonly known as The Culture Wars, not only offering a stinging critique of the monoculturalist position during the Culture Wars, but carrying out this critique specifically through an Afro-Asian analysis of white supremacy and American imperialism. Reed effectively demonstrates how defenders of a white Western view of history were trafficking in the very “revisionism” and “feel-good ethnocentrism” that they attributed to multiculturalists. And at the same time, Reed did not spare the left, skewering cynical lefty careerist academics for their complicity with the Ivory Tower’s white supremacist power structure.

At its best Japanese by Spring is an example of what David Palumbo-Liu calls a “critical multiculturalism,” that is, a multiculturalism which “explores the fissures, tensions, and sometimes contradictory demands of multiple cultures, rather than (only) celebrating the plurality of cultures by passing through them appreciatively.”1 Reed takes the term “culture war” and stretches the phrase out to its fullest absurd comic potential, insisting that the actual United States wars of the 20th century are inseparable from culture wars rhetoric.

The opening paragraph of the novel contains everything that makes Japanese by Spring such a unique piece of creative work, from its examination of multiculturalism and academia, to its emphasis on militarism, to Reed’s formal deployment of the academic novel genre, to his Afro-Orientalist critique of American imperialism, to the strategies of black literary satire as a vehicle for political commentary.

When Benjamin “Chappie” Puttbutt’s mom and dad said Off to the Wars, they really meant it. George Eliott Putbutt was a two-star Air Force general, cited and decorated for distinguishing himself in two of the three great yellow wars, the wars against Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, and Ruby Puttbutt’s star was on the rise as a member of the United States Intelligence community. As a military brat Benjamin knew the techniques of survival and so, after reading that Japan would become a future world power, Puttbutt began to study Japanese while enrolled at the Air Force Academy during the middle sixties. It was the end of an upbringing characterized by regimen and discipline. George and Ruby Puttbutt’s idea of education was similar to John Milton’s. In his “Of Education,” he recommends that “two hours before supper [students]…be called out to their military motions, under sky or convert according to the season, as was the Roman wont; first on foot, then, as their age permits, on horseback, to all the art of cavalry…in all the skill of embattling…fortifying, besieging, and battering, with all the helps of ancient and modern stratagems tactics and warlike maxims.” That’s not the only attitude they shared with Milton. With their continuous need for enemies, their motto could have been taken from Milton’s panegyric for Cromwell: New Foes Arise.: Their favorite blues singer was “Little Milton.” Their favorite comedian Milton Berle.2

The paragraph introduces the main character Professor Benjamin “Chappie” Puttbutt, and lays out the novel’s main concerns about culture, education and warfare while also exemplifying Reed’s unique narrative style full of wit, puns and allusions, a style heavily influenced by Reed’s interest in jazz music and jazz poetry.

And, as the paragraph foreshadows, Puttbutt’s study of Japanese would eventually turn out to be an advantage. The major surreal turn in the novel comes at the end of its second section, when Jack London College is purchased by a mysterious Japanese corporate faction. Puttbutt is called into the new administration office and finds Dr. Yamato, his Japanese language instructor sitting there. Yamato wants to hire Puttbutt as his special assistant, an appointment in which he will act as a liaison between the new Japanese administration and the college’s faculty. Under the new administration, courses in Japanese language history and culture became the dominant courses in the curriculum, and the Western based Department of Humanity was downgraded to a subdivision of the Ethnic Studies department.

Here, Reed is intentionally playing with his monocultural and multicultural paradigm, placing the “Back to Basics” defenders of Western civilization in the position of just another minor intellectual field in a world run by a different set of monoculturalists. Through the autobiographical insertion of “Ishmael Reed” as a character, and through the inclusion of passages about Japanese and Yoruba grammar, Reed constructs Japanese by Spring as a multilingual and multicultural text. As he writes, “Chappie knew that if he couldn’t learn Spanish and Japanese he’d be obsolete in the 1990s United States. Unless they expand and absorb, languages die, and already English was hungry for new adjectives, verbs and nouns.”3 Reed puts his theory of multiculturalism into practice by creating an academic novel that intensively embraces America’s inherently multicultural heritage by incorporating the critical study of languages into the narrative itself. And he challenges the white supremacist defenders of Western Civilization, calling them out as an anti-intellectual coalition hiding from the complexities of a multicultural world.