Crossover, Convergence, and the Cultural Politics of Black Comics

This guest post is part of our new blog series on Comics, Race, and Society, edited by Julian Chambliss and Walter Greason.

There has never been a better time to be a Black comics fan or a scholar immersed in Black nerd culture. This is a declaration: it aims to inaugurate a distinct situation by invoking it verbally. By announcing a breakthrough moment for Blackness and comics in the present, I echo the paradigmatic naming performed by the creator-owned superhero comics company Milestone Media.

Milestone’s comics gave new meaning to the term “crossover” in popular culture. Seizing the day by taking advantage of a unique set of conditions for the production and dissemination of knowledge has been a core strategy for Black culture workers ever since we fashioned ourselves into the “New Negro,” converging on a new self-concept through interventions across a variety of art forms, academic disciplines, and social movements. Crossover and convergence, two related concepts in media and communication, have a far-reaching intellectual legacy that helps explain the challenges and opportunities occasioned by the current proliferation of Black images derived from comics throughout other sites on the media landscape.

The term crossover typically connotes a product’s penetration into multiple segments of a consumer base constructed in demographic terms. In comic books and other narrative media, crossover refers to the appearance of characters and plot developments originating from one narrative in one or more installments of another narrative. As an example of the television equivalent, consider the 2015 appearance of the lead actors from the Fox series Bones and Sleepy Hollow on episodes of one another’s respective shows during the same night of primetime programming. Regarding the present context for these developments, critics describe convergence as the flow of content across media and the movement of audiences through these information flows. Daya Kishan Thussu and other scholars note that this flow of people and knowledge occurs in both directions, from Diasporic circuits to national capitals, and vice-versa.

I recommend using the notions of crossover and convergence to describe tendencies in cultural production that betray the organization of the popular imaginary by the social. Popular media doesn’t provide perfect reflections of the social world, nor does it simply give form to the collective fantasies of the populace—it mediates between these domains, passing perceptions and fantasies through a filter of institutions shot through with agendas, desires, and other ideological structures. These forces are often in conflict, and cultural institutions bring them together in contradictory ways.

While social conventions like compulsory heterosexuality and racial hierarchy have a powerful hold on our imaginations, masking persistent contradictions and allowing for the seamless reproduction of ideological “facts” everywhere we look, crossover names the incursion of otherwise unspeakable possibilities into venues where they do not belong. In this sense, crossover assigns cultural significance to moments that appear to represent “politics” intruding into culture by associating these developments with aesthetic, intellectual, and psychological currents already at work within an artistic tradition. By staging their interventions in cultural terms—as the inauguration of new schools of thought or movements that sediment into the historical record as periods—artistic innovators concerned with renovating race thinking can claim grounds besides the political for their departures from convention, if they so choose. In the process, they can call attention to the way the established norms of cultural production allow the status quo to masquerade itself as apolitical.

The conceit of the New Negro is one point of departure for questioning what’s new about Blackness in comics today and what we have inherited from prior generations. The New Negro is a cipher for many theoretical considerations, not least of which is the question of whether there is anything new about Black being in the “New World.” When millions of Black people chose to steal away from the country to the city, they brought their dilemmas with them. In the minds of some, planting seeds in new soil allowed the New Negro to escape being “more of a formula than a man,” conditions in which his “shadow, so to speak, has been more real to him than his personality.” For others, the moment held no renewed promise of social mobility, only a temporary opening through which a fortunate few passed into the American capitalist hierarchy.

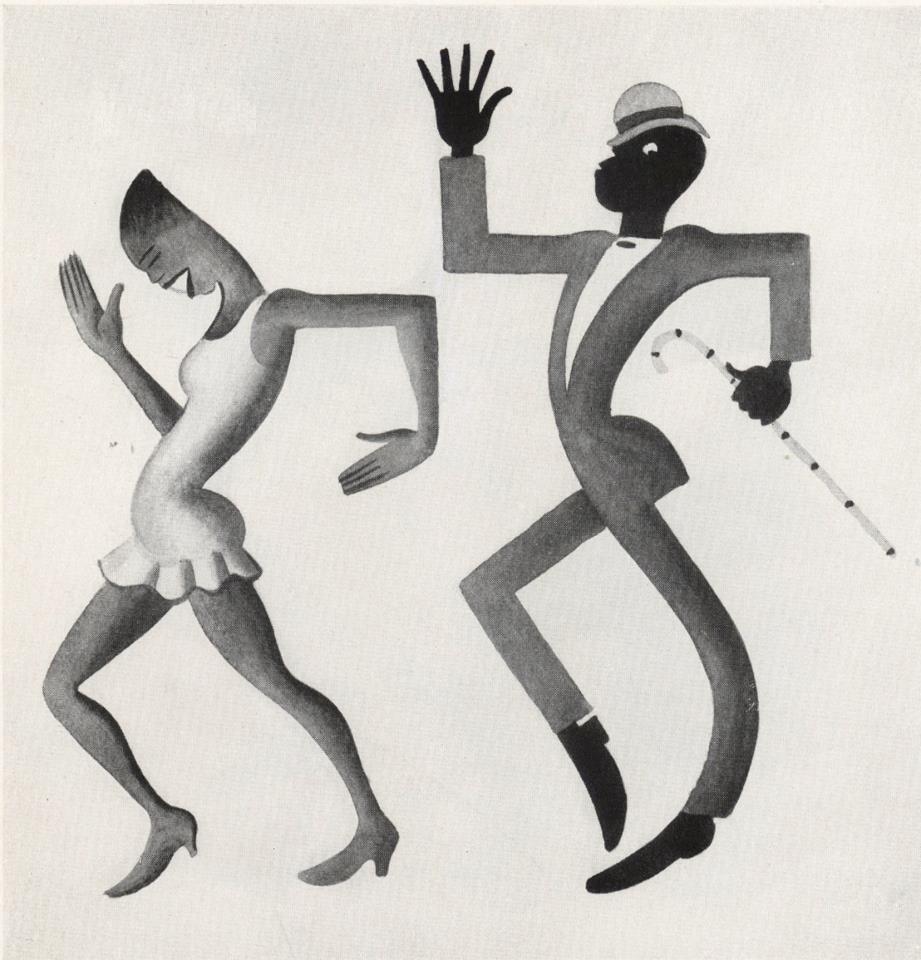

Both these realities are mediated through the graphic arts of the period in the caricatures of Miguel Covarrubias. In his Negro Drawings and illustrations for books by W.C. Handy, Langston Hughes, and Zora Neale Hurston, Covarrubias exploded Black bodies and personalities to comic proportions. Caricatures are notoriously effective for visualizing racial difference and sexual pathology, but Covarrubias’s use of the technique remediated this legacy by conferring images of Black joy and wonder into a burgeoning repertoire of modernist illustration alongside portraits of white cognoscenti and socialites. His Negro drawings betray the quality of “animatedness” articulated by Sianne Ngai: susceptible to external prodding, liable to entertain, but possessed of overly expressive bodies that make them prone to slippage and spontaneity of their own accord.

Whether they are dancing or praying, Covarrubias’s cartoon Negroes often hold arms akimbo and mouths agape, the angularity of their hats brimming with potential energy. These caricatures valorize primitivism by translating the performance of racial distinctiveness in everyday life from three dimensions into two, and they also consign Blackness to the register of the cartoon, a formal precursor to the work of art.

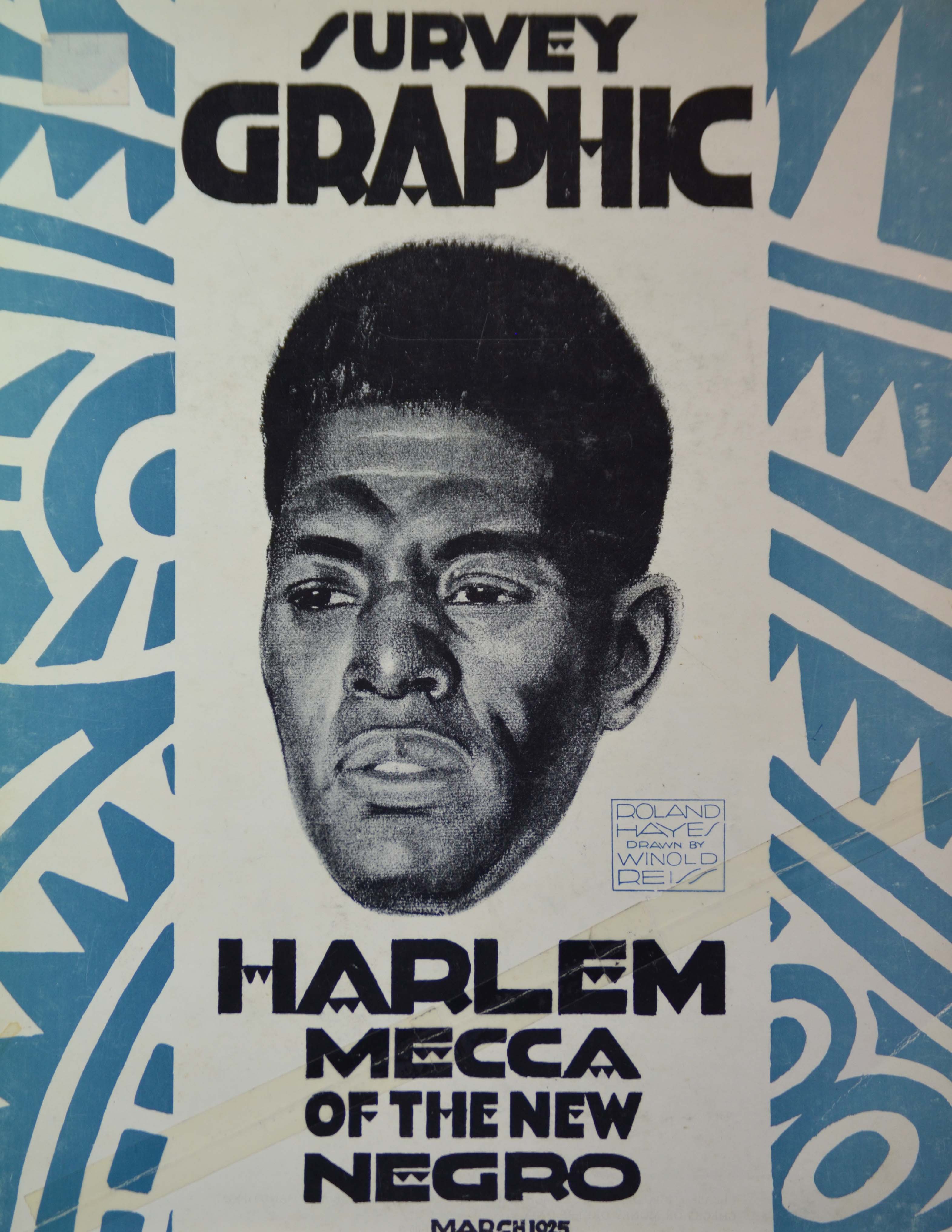

The concerted effort to construct the New Negro in visual, musical, literary, and scientific discourse enlisted print cultures as diverse as Vanity Fair, Opportunity, Survey Graphic, and Fire!! in the work of placing a new protagonist on the world stage. The dramatization of the New Negro’s emergence through literature and theater corroborated tabloid accounts that conjured nightlife and other exotic scenes for readers.

Later twentieth-century comics reiterated this pattern by propagating stereotypes and cashing in on Blaxploitation imagery. While the minstrel idiom produced the first Black images in print and material culture, including comic strips, some instances of blackface imagery crossing over into comics, such as Ebony White in Will Eisner’s celebrated The Spirit, betrayed a striking contrast between the continued use of caricature to objectify Blackness and the realistic visual style that idealized whiteness. In the later example of Blaxploitation comics, a cluster of body types, naming conventions, and formulaic plots suffuses one art form and then another. Just as Blaxploitation cinema commoditized the iconography of the Black Power and Black Arts movements, the floating signifiers of Black macho gave rise to comic book figures like Luke Cage: Hero for Hire, Black Lightning, Black Manta, Black Goliath, Black Panther, and Brother Voodoo. Like their white counterparts in print and their predecessors on screen, these muscle-bound Black heroes recapitulated patriarchy, notwithstanding the influence of women on Black militancy and the emergence of Black feminist exemplars from the same social ferment.

Where exploitative images of Black womanhood crossed over into comics, they enacted the pornotroping tendencies that account for the resemblance between Misty Knight and the title characters of films like Coffy and Cleopatra Jones. However, the longevity and subsequent renovation of these iconographies has extended their meanings in unanticipated ways. Media consolidation and the concomitant revitalization of comics through convergence–with blockbuster films and television series mining the archives of comics for content–have given a second life to some of these bygone icons. For instance, the television rendition of Luke Cage calls for the specific task of Black women’s performance, casting Simone Missick in the reimagined role of Detective Mercedes Knight.

Rather than a continuous flow of hegemonic gender ideology and race thinking from one cultural task to another, the contemporary contra-flow of Black innovation reintroduces fragmentation into convergence culture. In the hands of Black people, image-making practices that once normalized exploitative relations of representation become the means to reconfigure the politics of representation.

In the interventions of Ta-Nehisi Coates, Roxane Gay, and Yona Harvey, Amandla Stenberg and Ashley Woods, John Jennings, and Erika Alexander, crossover names the efforts of Black artists who have proven their talents elsewhere to learn from and contribute to new endeavors, and convergence names the migration of audiences and their desires to new horizons. The singular quality of work produced in this moment is not that it’s unprecedented, but rather, that it sustains the trailblazing efforts of elders like Rupert Kinnard and ancestors like Jackie Ormes.

André Carrington is an Assistant Professor of English at Drexel University. His research focuses on the cultural politics of race, gender, and genre in 20th century Black and American literature and the arts. He is the author of Speculative Blackness: The Future of Race in Science Fiction (University of Minnesota Press 2016). Follow him on Twitter @prof_carrington.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.