Crossing the Ecclesiastical Color Line: Black Churchgoers in Multiracial Congregations

*This post is part of our online forum with the Pew Research Center.

A massive study of Black churchgoers by Pew Research reveals that while Black churches still hold a singular place in the religious landscape, many Black Christians are worshiping across the color line. Even though these findings may seem surprising, and they do indicate a rise in cross-racial congregations, there has always been a degree of interracial interaction in ecclesiastical bodies.

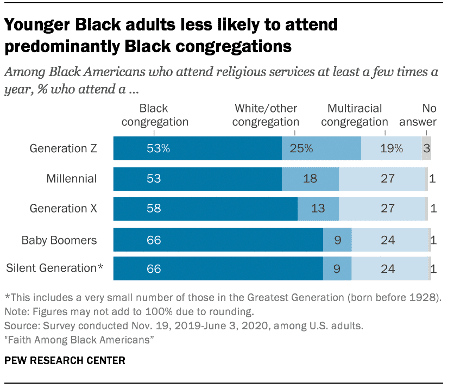

The Pew study found that, overall, 60 percent of Black churchgoers attend Black churches where “all or most attendees are Black and the senior religious leaders are Black.” Thirteen percent attend a church that is predominantly white (or Hispanic or Asian), and 25 percent attend a multiracial church where “no single race makes up a majority of attendees.”

The data further reveals that among younger Black people, a small majority still goes to a Black church, but significant numbers do not. Fifty-three percent of Millennials attend a Black church, but 18 percent attend a white/other church and 27 percent attend a multiracial church. Fifty-three percent of Gen Zers (born 1996 and after) attend a Black church, but 25 percent attend a white/other congregation and 19 percent go to a multiracial church.

These data follow a trend in the growth of multiracial churches—where at least 20 percent of the congregation is comprised of people of color–over the past two decades. A study on multiracial congregations found that the percentage of such congregations increased from 6 percent in 1998 to 19 percent in 2019.

This racial reshuffling, however, has been almost entirely one-way. “All the growth [in multiracial churches] has been people of color moving into white churches,” sociologist Michael Emerson says. “We have seen zero change in the percentage of whites moving into churches of color.” In addition, the percentage of Black attendees at multiracial churches actually declined from 27 percent in 2012 to 21 percent in 2019, suggesting that the political and social climate around elections and continued racial unrest may affect a Black person’s decision to remain in a multiracial congregation.

The fact that half of all Black churchgoers still attend a predominantly Black church, juxtaposed with increasing numbers who attend white or multiracial congregations calls into question the future of the Black church in reference to its past. Upon closer examination, however, churches in the United States have never been uniformly segregated along racial lines. There has always been a degree of racial mixing in churches even as there is still much truth to the adage “11 o’clock a.m. on Sunday morning is the most segregated hour in America.”

In the years prior to the Civil War, some racial integration in Christian churches occurred, but mainly as a way for white leaders to control the actions and religious life of Black people. As Charles F. Irons wrote in The Origins of Proslavery Christianity, “Sunday morning only became the most segregated time of the week after the Civil War. Before emancipation, black and white evangelicals typically prayed, sang, and worshiped together.”1

Yet even under the same roof, Black people were treated as second-class citizens in the household of God. In one example, Anglican leaders excised portions and even entire books of the Bible to form an edited “Slave Bible” that emphasized obedience to earthly masters and hard work–messages befitting the moral uplift and diligence of people who were considered property and enslaved for life.

Never content with an inferior position in white churches and denominations, after the Civil War Black Christians quickly mobilized their own fellowships and denominations. As soon as they could feasibly extricate themselves from predominantly white congregations, they did so with speed and creativity. Several historically Black denominations still in operation today trace their origins to the years following emancipation including the Christian (formerly Colored) Methodist Episcopal Church (1870), the National Baptist Convention (1895), and the Church of God in Christ (1907).

Yet there was always a contingent of Christians who were open to racial integration in churches and made attempts to form interracial worship spaces. In 1906, William Seymour, a Black preacher and evangelist, led a religious revival that witnesses said included speaking in tongues, miraculous healings, and holy trances. At first, these meetings, which lasted for months, included people of various races. One attendee reflected, “Blacks, whites, Chinese, and even Jews attended side by side to hear Seymour preach.”2 Despite these interracial beginnings, however, Pentecostals would eventually split along racial lines.

Other attempts at interracial worship occurred in the twentieth century. Although such initiatives were rare, they were ambitious. In 1944, the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco held its first official worship service. Albert J. Fisk, a white Presbyterian minister and professor, spearheaded the effort to form an interracial church. He invited renowned Black theologian and preacher, Howard Thurman to co-pastor the new congregation.

Thurman was thrilled the prospect. In correspondence with Alfred Fisk about the prospect of starting the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples, Thurman wrote, “It seems to me to be the most significant single step that institutional Christianity is taking in the direction of a really new order for America.”3

Before Thurman, who had to fulfill duties at his current post at Howard University, could begin, a fiery young minister named Albert Cleage Jr. filled in. Cleage quickly grew disillusioned with the interracial endeavor which he thought was geared more toward the comfort of white people than the liberation of Black people. According to Cleage, white people at Fellowship “wanted to do something meaningful,” but they had “no understanding of tension and power.”4

While the number of multiracial congregations has tripled over the course of 20 years, interracial worship among Black and white churchgoers remains a tenuous proposition. Sociologist Korie L. Edwards of The Ohio State University records in her book, The Elusive Dream, that for white people at these churches “their sense of connectedness to the church was fragile and dependent upon the church’s affirmation of whiteness.”5 When white people feel their priorities and preferences being challenged, they often leave multiracial church settings.

Black people’s investment in multiracial churches is waning as well. In 2018, a New York Times article by Campbell Robertson detailed the movement of Black Christians out of predominantly white churches due to Trumpism and racial insensitivity. “It has been a scattered exodus — a few here, a few there — and mostly quiet, more in fatigue and heartbreak than outrage.” Black people’s hope that faith in the same religious would result in racial reconciliation have often been frustrated. The departure of Black Christians from white religious spaces indicates that even in interracial settings, people of color can face insurmountable obstacles to integration.

The data from the Pew Research study on Black worshipers shows the continued salience of predominantly Black churches. More than half of people in all age groups still attend a Black church. There is an increasing trend, however, toward Black churchgoers, especially among the younger generations, choosing white and multiracial congregations as their faith communities.

It appears that there will always be some attempts at forming multiracial faith communities and that Black people will engage in such efforts on the proposition that their presence in other congregations will be accepted and even transformative. It also appears that if Black people continue to face racism and pressure to culturally assimilate, then there will always be a need for and the presence of predominantly Black churches.

- Charles F. Irons. The Origins of Proslavery Christianity: White and Black Evangelicals in Colonial and Antebellum Virginia. (Chapel Hill, NC, 2008), 1. ↩

- Frank Bartleman. Azusa Street: An Eyewitness Account. (Alucha, FL, 1980), 59. ↩

- Paul Harvey, Howard Thurman and the Disinherited: A Religious Biography (Grand Rapids, MI, 2020), 123. ↩

- Peter Eisenstadt, Against the Hounds of Hell: A Life of Howard Thurman (Charlottesville, VA, 2021), 215. ↩

- Korie L. Edwards. The Elusive Dream: The Power of Race in Interracial Churches. (Oxford, 2008), 128. ↩

be interested in knowing if the majority of mixed congregations are in non-denom/evangelical/gospel-of-prosperity churches vs mainline?