CORE and the Early Civil Rights Movement in Los Angeles

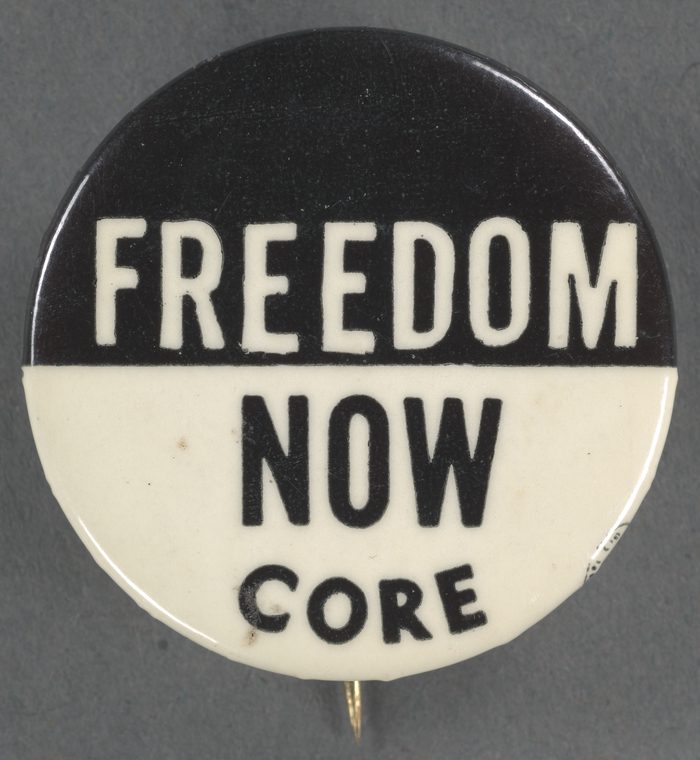

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was founded in the spring of 1942 in Chicago by James Farmer along with a racially diverse group of liberals, pacifists, socialists, and religious groups, most of whom were college students. From its origin and expansion throughout the country, CORE was committed to interracialism and nonviolent direct action. With branches from Brooklyn to Seattle, CORE was a major organization in the struggle for civil rights and racial justice in the mid-twentieth century. By 1947, CORE had affiliates in nearly two dozen cities around the United States, including Los Angeles. Through numerous actions and collaborations, Los Angeles CORE played an important part in the early phase of the Civil Rights Movement.

One of the first major actions was a sit-in at Bullock’s Broadway stores tea room on Saturday, June 28, 1947, when members took up twenty tables from 11:30am-3:30pm. Black people were not being served in this establishment, nor were the racially mixed tables. Some sympathetic whites refused service until the Black people were served, with some whites asking to be notified how they can be involved to address such racial injustice. CORE, with support from other groups, visited the tea room weekly to protest the lack of service for Black people. As a result of protests and civil suits brought against Bullock’s, the plaintiffs won a $425,000 suit against the store. In addition, CORE chairman Manuel Talley stated that in early August “approximately 100 persons organized by CORE returned to the store for one of their customary ‘sit-ins’, for the first time Negroes were ‘served’ promptly. Even hurriedly.”

Under the leadership of Herbert Kelman and Henry Hodge, CORE led successful campaigns that integrated Union Station’s coffee shop and barbershop, but the organization faltered by 1957 after unsuccessful campaigns to end racial discrimination in major downtown department stores. CORE really wanted to attack racially segregated housing in Los Angeles but was limited in membership and resources for such an undertaking. Instead they continued to address employment discrimination, such as the joint CORE-National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) campaign for truck drivers’ jobs in the spring of 1958. With the inability to loosen the teamsters hold, CORE redirected its efforts to testing motels to see if they accepted Black guests. Earl Walters, head of Los Angeles CORE said they, “tested 70 hotels and motels to see if they would accept Negroes, and took about a dozen to court.” He continued reporting, “In 1957, upward of 70% would not accept Negroes” but by 1963 “better than 65% will.” CORE also supported the Los Angeles committee for the Youth March for Integrated Schools which held a rally on Saturday April 18, 1959, to “demonstrate local support for the passage of the Douglas-Celler-Javits-Powell civil rights bill and for speedier integration of the nation’s schools” after the Brown v. Board decision. Then on June 12 and 13, 1959, CORE held a series of community workshops at Vermont Square Methodist Church about nonviolent direct-action in an effort to increase support and membership. The workshops were the kickoff programs for the CORE National Conference from June 14 to 19 at Presbyterian Conference camp in Pacific Palisades. The theme was “The Struggle for Racial Equality, from the World to your Doorstep.”

On February 1, 1960, four Black students from North Carolina Agriculture and Technical College in Greensboro, North Carolina, staged sit-ins at a Woolworths lunch counter. They refused to move from the lunch counters until the counters were desegregated. After purchasing items from other parts of the store to establish they were paying customers and not trespassing, these youth demanded to be served like the white patrons. This sit-in would launch over 200 sit-ins throughout the South. That March CORE sent field secretary James McCain west to Portland, Oregon, to Berkley, and Los Angeles to assist local chapters with organizing solidarity demonstrations against the chain variety stores. The CORE-led demonstrations included groups such as the NAACP, the International Ladies Garment Workers (ILGWU), the United Auto Workers (UAW), and the American Jewish Congress. In the early part of March 1960, the Los Angeles chapter of CORE picketed seventeen Kress and Woolworths five and dime stores in solidarity with other nonviolent direct-action campaigns. By mid-month, the Southern California Boycott Committee (SCBC) formed under the leadership of Jesse Morris Jr. and students Walter Davis of Los Angeles State College as well as Dave Axelrod and Robert Farrell of UCLA. A boycott, SCBC hoped, would put pressure on Kress and Woolworths to change their discriminatory practices.

The Los Angeles Sentinel reported that the SCBC urged the public to “help in our fight for universal equality.” They organized to picket Woolworths in Santa Monica and Downtown Los Angeles. As the Los Angeles Times reported, “They marched up and down in front of the stores carrying signs reading ‘Kress- Stop Supporting Segregation’, ‘We Protest Woolworth’s Southern Policy’, ‘Did They Die in Vain at Gettysburg?’, and ‘Woolworth’s- Let My People Eat’.” This exhibition of nonviolent direct action put theory into practice by seeking 1.) disruption of the status quo; 2.) bringing negative attention to the company ultimately affecting profits; and 3.) the attention of decision makers to make the desired legislative and policy-oriented changes.

The signs in Los Angeles clearly communicated messages of solidarity with freedom fighters in the South. Farrell, UCLA class of ’61 and later to become a Los Angeles City Councilmember, reflected on protesting segregation and discrimination in Los Angeles by stating:

it came out of just shared experiences and feelings and a sense that in the late 1950s people were doing something about those kind of circumstances in other parts of the United States, and some of us felt that we should do something about it here.

Brown v Board of Education of Topeka, the murder of Emmett Till, the Montgomery Bus Boycott, “The Little Rock Nine” integrating Central High School in Arkansas, and President Dwight Eisenhower signing the Civil Rights Act of 1957 were some of the major events contributing to the Black Freedom Movement in the 1950s. Farrell reveals the hope and faith of a generation believing that, through nonviolent direct-action protests and demonstrations, radical changes to racially discriminatory de jure and de facto laws would occur.

As the sit-in solidarity campaigned waned, CORE chapters shifted attention to assisting sharecroppers in the South. In Fayette and Haywood counties in Southwestern Tennessee, voter registration campaigns had been so successful that the white community retaliated with severe economic repression. Robert and Helen Singleton, Jesse Morris Jr., and others worked with Earl Walter on the “Help Haywood County” campaign in September of 1960. Joining chapters in St. Louis, New York, and Chicago, Los Angeles CORE solicited donations of food and clothing for the 400 economically oppressed families in Haywood County and Fayette County in Tennessee. They coordinated efforts with the Fayette and Haywood County Leagues. Morris and Walter credited the success of the project to the generosity of the numerous civic, social, religious, industrial, labor union, civil rights and others, including Mr. and Miss Los Angeles.

CORE was very active in the South during the Civil Rights Movement, but it also had a presence around the nation, including Los Angeles. It is critical to recognize the contributions of CORE and other civil rights organizations outside of the South to the broader Black freedom struggle. Los Angeles CORE’s work at the community level in their city and elsewhere made them an indispensable part of the solidarity network that drove the desegregation movement.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

CORE was active in the Midwest. Columbus, Ohio

but there was a big split when whites were removed.

I respect the time put into writing this short historical moment that most of our young people are not educated on. Our grandparents/parents were born either during this time or directly after which begets others that are to come. Having to be equipped with knowledge about African Americans are essential to how WE carry ourselves! (Yes, I am African American)!