Contested Bodies: A New Book on Black Motherhood and Slavery in Jamaica

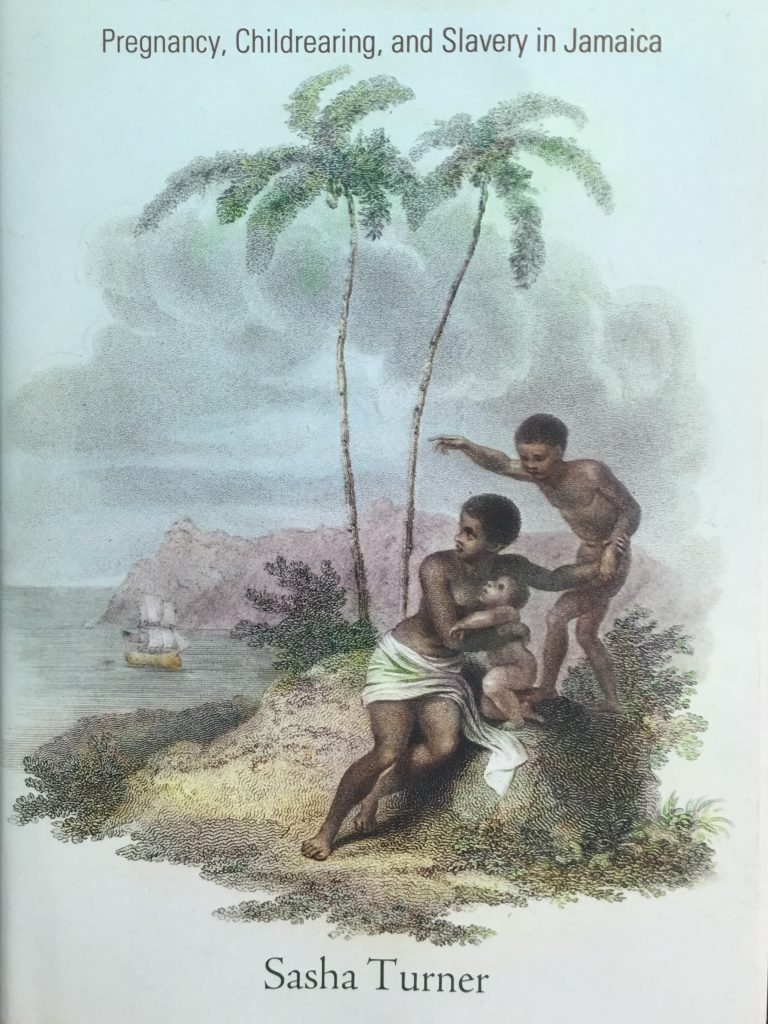

This post is part of my blog series that announces the publication of selected new books in African American History and African Diaspora Studies. Contested Bodies: Pregnancy, Childrearing, and Slavery in Jamaica was recently published by the University of Pennsylvania Press.

***

The author of Contested Bodies is Sasha Turner, who is Associate Professor of History at Quinnipiac University. Professor Turner is a historian of slavery, the Caribbean, and the African Diaspora, with research interests in gender, race, and the body, and women, children, and emotions. Several journals, including Journal of Women’s History, Slavery and Abolition, and Caribbean Studies have published her research. She was awarded the Rutgers University Race, Ethnicity, and Gender Studies Fellowship, the Washington University in St. Louis African and African American Studies Fellowship, and the Richards Civil War Era Center and Africana Research Center Fellowship at the Pennsylvania State University. In Fall 2017, Professor Turner will continue research on her new book project, tentatively titled Slavery, Emotions, and Gendered Power, as a Fellow at Yale University’s Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition. Professor Turner has delivered talks around the world, including proceedings in the Caribbean and the United Kingdom commemorating the 200-year abolition of the transatlantic slave trade and the United Nations annual Commemoration and Briefing on the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Follow Professor Turner on Twitter @drsashaturner.

The author of Contested Bodies is Sasha Turner, who is Associate Professor of History at Quinnipiac University. Professor Turner is a historian of slavery, the Caribbean, and the African Diaspora, with research interests in gender, race, and the body, and women, children, and emotions. Several journals, including Journal of Women’s History, Slavery and Abolition, and Caribbean Studies have published her research. She was awarded the Rutgers University Race, Ethnicity, and Gender Studies Fellowship, the Washington University in St. Louis African and African American Studies Fellowship, and the Richards Civil War Era Center and Africana Research Center Fellowship at the Pennsylvania State University. In Fall 2017, Professor Turner will continue research on her new book project, tentatively titled Slavery, Emotions, and Gendered Power, as a Fellow at Yale University’s Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition. Professor Turner has delivered talks around the world, including proceedings in the Caribbean and the United Kingdom commemorating the 200-year abolition of the transatlantic slave trade and the United Nations annual Commemoration and Briefing on the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Follow Professor Turner on Twitter @drsashaturner.

It is often thought that slaveholders only began to show an interest in female slaves’ reproductive health after the British government banned the importation of Africans into its West Indian colonies in 1807. However, as Sasha Turner shows in this illuminating study, for almost thirty years before the slave trade ended, Jamaican slaveholders and doctors adjusted slave women’s labor, discipline, and health care to increase birth rates and ensure that infants lived to become adult workers. Although slaves’ interests in healthy pregnancies and babies aligned with those of their masters, enslaved mothers, healers, family, and community members distrusted their owners’ medicine and benevolence. Turner contends that the social bonds and cultural practices created around reproductive health care and childbirth challenged the economic purposes slaveholders gave to birthing and raising children.

Through powerful stories that place the reader on the ground in plantation-era Jamaica, Contested Bodies reveals enslaved women’s contrasting ideas about maternity and raising children, which put them at odds not only with their owners but sometimes with abolitionists and enslaved men. Turner argues that, as the source of new labor, these women created rituals, customs, and relationships around pregnancy, childbirth, and childrearing that enabled them at times to dictate the nature and pace of their work as well as their value. Drawing on a wide range of sources—including plantation records, abolitionist treatises, legislative documents, slave narratives, runaway advertisements, proslavery literature, and planter correspondence—Contested Bodies yields a fresh account of how the end of the slave trade changed the bodily experiences of those still enslaved in Jamaica.

An original and timely intervention in the histories of slavery, gender, and labor. In arguing that reproduction played a crucial role across a number of political and social divides, Contested Bodies becomes an excellent window through which we can understand the economies (both moral and financial), culture, intimacies, protests, labor, and power in which the institution of slavery is imbricated.” —Jennifer L. Morgan, New York University

Ibram X. Kendi: Please share with us the creation story of this project.

Sasha Turner: Foraging through a collection of letters known as the Penrhyn manuscripts, I became preoccupied by a letter written on August 6, 1807 by David Ewart, attorney or head manager at Kings Valley sugar estate in western Jamaica. Its recipient was the Right Hon. Richard Lord Penrhyn, Ewart’s employer and the Kings Valley estate’s proprietor who resided in England and had served multiple times as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Liverpool, a thriving transatlantic trading hub. Penned five months after the British Parliament prohibited importing African captives to its colonies, Ewart’s letter reassured Lord Penrhyn that he had been promoting the biological reproduction of slaves on Penrhyn’s Jamaica sugar estate. Ewart carefully calculated the weight of loads female slaves carried and the distance traveled against visible evidence of pregnancy and crude estimates on how close women were to giving birth, reorganizing enslaved women’s labor roles to protect their pregnancies.

It was not coincidental that Ewart’s discussion of pregnancy and its potential for reshaping enslaved women’s working lives intrigued me. Questions about cultural attitudes toward pregnancy and how they shaped women’s lived experiences haunted my archival quest.

Growing up in Jamaica and engaging with slavery history throughout my undergraduate career stirred curiosities about women’s childbearing lives. I grew up in the 1990s to early 2000s Jamaica, where the National Family Planning Board campaigned to limit family sizes as a poverty alleviation strategy. Jamaican women’s supposedly high fertility rates threatened social and economic stability. I remember these campaigns vividly not only because the Board’s messaging, “two is better than too many,” blasted on the radio and roadway billboards. I remember these campaigns because by the time I became a history major at the University of the West Indies, Mona, I discovered that the putative problem of Afro-Jamaican women’s extraordinary fertility was a recurring theme in our history.

From my undergraduate lectures and the works of Verene Shepherd, Hilary Beckles, Barbara Bush, and Deborah Gray White, I saw the repeated assertion made by enslavers that enslaved women were exceptionally fecund. But behind these assertions was a more complicated story. As Deborah Gray White explained it, slaveholders depicted black women as Jezebels whose insatiable sexual appetite corrupted white men and allowed black women to bear more children than white counterparts. Not only was the image of the Jezebel proslavery propaganda that justified the s/exploitation of black women, enslaved women also did not bear enough children to replenish the population. Demanding work regimes, brutal punishment, premature death, and high rates of illness and disease made it nearly impossible for enslaved women to conceive and raise children.

It was against this background that I took a closer look at David Ewart’s letter. Here I had found evidence that suggested that enslavers adopted measures to protect enslaved women’s pregnancies. My quest was to figure out how far the experiences of enslaved women under Ewart’s care were reflected in the wider Jamaican slavery culture. This quest took me down the path of what became Contested Bodies.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.