“Concede Nothing” – How to Remember a Storm Ten Years Later

This year marked ten years since Hurricane Katrina made landfall. To say New Orleans and the entire Gulf Coast would never be the same does not capture the impact of the storm. The United States wouldn’t be the same. On August 29, 2005, when Katrina made landfall and levees across the city broke, a rainbow of systemic and superstructure fantasies built on ignoring black poverty, environmental safety, and uneven community development shattered. George Bush didn’t care about black people. Neither, come to find out, did emergency management officials charged with shepherding everyone out of the city but who left few resources to move the sick, disabled, elderly, poor, or incarcerated out of the way of the coming storm. Or law enforcement officials at the local or national levels who threatened, bullied, harassed, and, yes, murdered, residents of the city in the name of order and to protect property. The list goes on and on…

Remembering Hurricane Katrina is a black intellectual history project. The disparate impact of the storm on the city’s black population makes remembering, documenting, and narrating the history of that moment an incredible responsibility. According to City Lab, “compared to 2000, about 100,000 fewer African Americans and 9,000 fewer whites live in New Orleans.” While the black population was decreasing before 2005, these numbers (including the racial disparity between) result almost entirely from the continuing impact of the storm. Many black New Orleanians were displaced, many of those displaced never returned, and many who remained or returned continue to choose to leave because of the changes happening around the city (high rents and affordable housing being the latest battle being waged by community groups and activists around a city which demolished the majority of its public housing units after 2005).

But New Orleans is also a deeply American city, one whose history often sings a canary’s song over what will unfold for people of African descent in this country, the Caribbean basin, and around the world. The Danzinger Bridge shootings didn’t foretell present-day police violence against black people in this country. That kind of violence has always been, but the unprovoked and willful shooting and wounding of four, murder of two New Orleans residents attempting to cross out of floodwaters and to safety using the bridge previewed the use of deadly force against black people as a matter of course by local and national law enforcement. Turning the clock back, Homer Plessy, the Slaughterhouse Cases, Les Cenelles (the first anthology of creole poetry by people of African descent to be published in the United States), the labor and leadership of spiritual workers like Marie Laveau and Henriette Delille, the 1811 slave revolt (the largest slave revolt to occur on U.S. soil), the frequency and agility of slaves who managed to escape into freedom, all of these mark the shape and tenor of black intellectual thought nurtured to bursting in an iconic city.

New Orleans black community has given birth to and influenced black intellectual traditions since its founding. What questions, then, do historians, scholars, and interested individuals need to ask about a moment like Hurricane Katrina in light of this past and our present?

DO pay attention to the tenor of the discussion

This year, much of the discussion around Hurricane Katrina and how to commemorate her split roughly along two camps.

On one side was Katrina 10: Resilient New Orleans (or #Katrina10 or #K10). Katrina 10, sponsored by the mayor’s office, supported a constellation of state and city institutions, community groups, leaders, activists and artists from around the city as they showcased the ways New Orleans had returned (past tense) to its former glory. Katrina 10 was the organization that helped support President Obama’s visit to the city. They also supported President Bush’s visit to the city. Katrina 10’s biggest funders included the Rockefeller Foundation, Walmart, Chevron, CitGo, McDonalds, and Southwest Airlines.

On the other was Katrina Truth: Resistant New Orleans (or #KatrinaTruth). Katrina Truth, a loosely organized coalition of community groups, artists, and activists, formed to protest the K10 narrative of resilience and return and a “comeback:”

“America’s best comeback city is one where the Black median income remains less than one half of the White median income. It is a city where the Black unemployment rate is nearly three times the rate of White unemployment. It is a city where only 30 percent of residents in the predominately Black Lower 9th Ward have been able to return to their homes as the mostly undamaged public housing they once lived in – and fought to stay in – were condemned after the storm.”

Katrina Truth was sponsored by the Advancement Project, Family and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children, and a number of other local, justice-oriented organizations who also did work hosting events (including a memorial event) and researching information about the state of black and poor lives in New Orleans from 2005 to 2015.

DON’T assume you know where someone falls in the debate because of their race

New Orleanians of all races and socieo-economic backgrounds participated in events, workshops, panel discussions, community forums, and protests along both sides of remembering. Many who returned, including black New Orleanians, look forward to moving past the events of the Storm. Many others do not. A photoessay by brilliant New Orleans photographer Patrick Melon captures the complexity and conflicting experiences that mark the very human responses to both remembering and experiencing the aftermath of the storm.

DON’T discount popular culture

When Kanye West suggested, “George Bush doesn’t care about black people,” shirts declaring “Kanye was right,” appeared almost immediately. Ten years later, NBC producers discussed what it meant to curate that moment and were candid about not wanting to make the fundraiser about race even as one producer admitted, “it was good TV.” Remembering Katrina also means remembering ways blackness, race, and media intersected in the past, and have come to intersect in the present:

What made it good TV? “The fact that it was controversial,” he said. “And it stopped everything cold.” The small studio audience that included celebrities like Lohan and DiCaprio was “eerily quiet.”

And despite the real human lives lost and impacted by the storm, George Bush remembers this statement and this moment as one of the worst moments of his presidency. And Bush gladly returned to New Orleans to speak on the city’s resilience this past August to lukewarm reception.

After the storm, David Simon began production on an HBO Series called, Tremé. The show ran for four seasons and continues to influence what migrants to the city expect to see. At the same time, the same black cultural institutions in the city like the Social Aid & Pleasure Clubs and the Mardi Gras Indians have had to fight lawsuits from new arrivals, furious with early morning and late night gatherings that have become a staple of those communities. People like Guardians of the Flame Big Queen Cherice Harrison-Nelson, who founded the Mardi Gras Indians Hall of Fame, have done much to raise awareness about the tribes and their work in the city, but tension continues.

Both of these examples, of many, are a reminder that there is nothing easy or casual about the ways media disseminates narratives or cultural institutions (in the city and beyond) operate. Triangulating the reality of cultural producers in the city with their portrayal pre- and post-storm cannot be discounted in how memories of the Storm and its aftermath are produced, or in what impacts the members of these communities in the present.

DO “Concede Nothing” (or, Don’t Make the Same Mistake Twice)

On the 10th anniversary of the story, Women With a Vision released a statement on the state of New Orleans, post-Katrina:

While some New Orleans neighborhoods and communities have rebounded, many of the communities that Women With a Vision stands beside every day have been left out (and pushed out) of the recovery process. Low-income communities, women of color, and LGBTQ communities of color continue to face difficulties in accessing many of the things needed to live in safety and wellness, including: affordable healthcare (exacerbated by the destruction of the city’s safety-net healthcare system); affordable housing (rents have more than doubled since Hurricane Katrina and continue to rise as gentrification takes root in several poor communities of color); healthy food and grocery stores; culturally-relevant education; functioning public transportation; and jobs that pay living wages.

This statement is one of the few (one of the only ones I’ve seen but I have not seen them all) which draws attention to LGBT communities of color, trans- and cis- women, at the same time that it draws attention to poor black and people of color in the city.

After the storm, members of the New Orleans chapter of INCITE: Women of Color Against Violence led by Shana Griffin committed energy, sweat, time, and peace of mind to starting a clinic for queer, and straight cis- women of color in the city. Named the New Orleans Women’s Clinic and located in the Tremé, it was established by the Women’s Health & Justice Initiative. That clinic did not survive but in the four years it was operation, it “provided safe, affordable, and non-coercive sexual and reproductive health services, education, and advocacy to approximately 8,800 low and working class women throughout the Greater New Orleans Metropolitan area in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.” For more on the clinic, listen here and here.

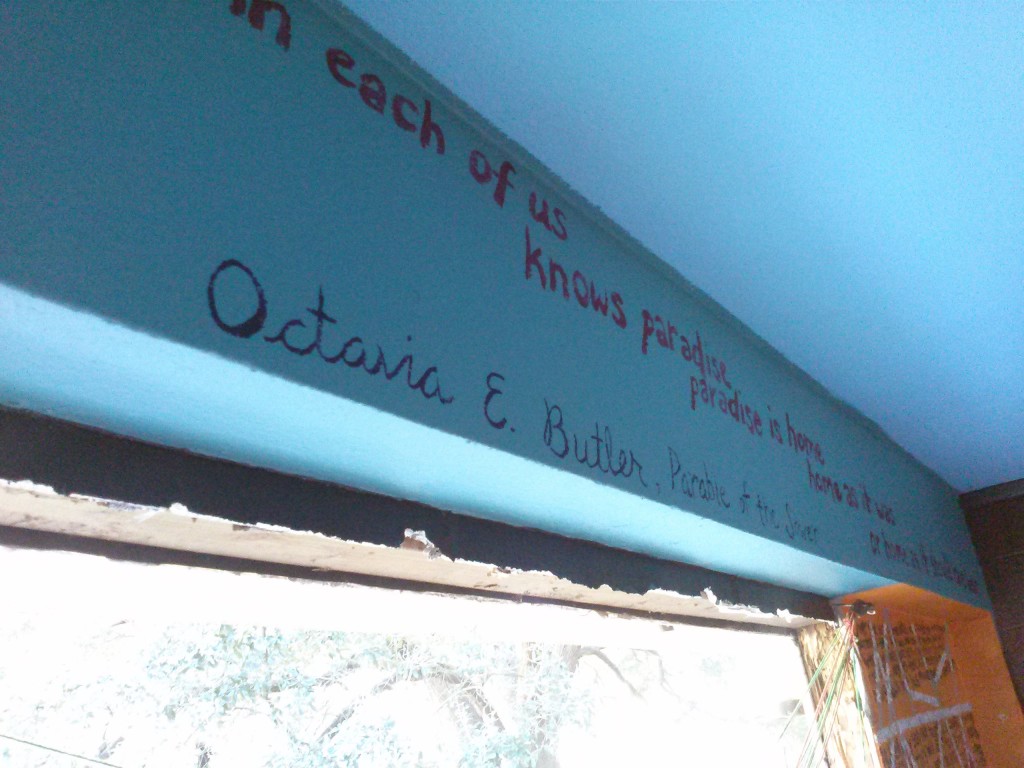

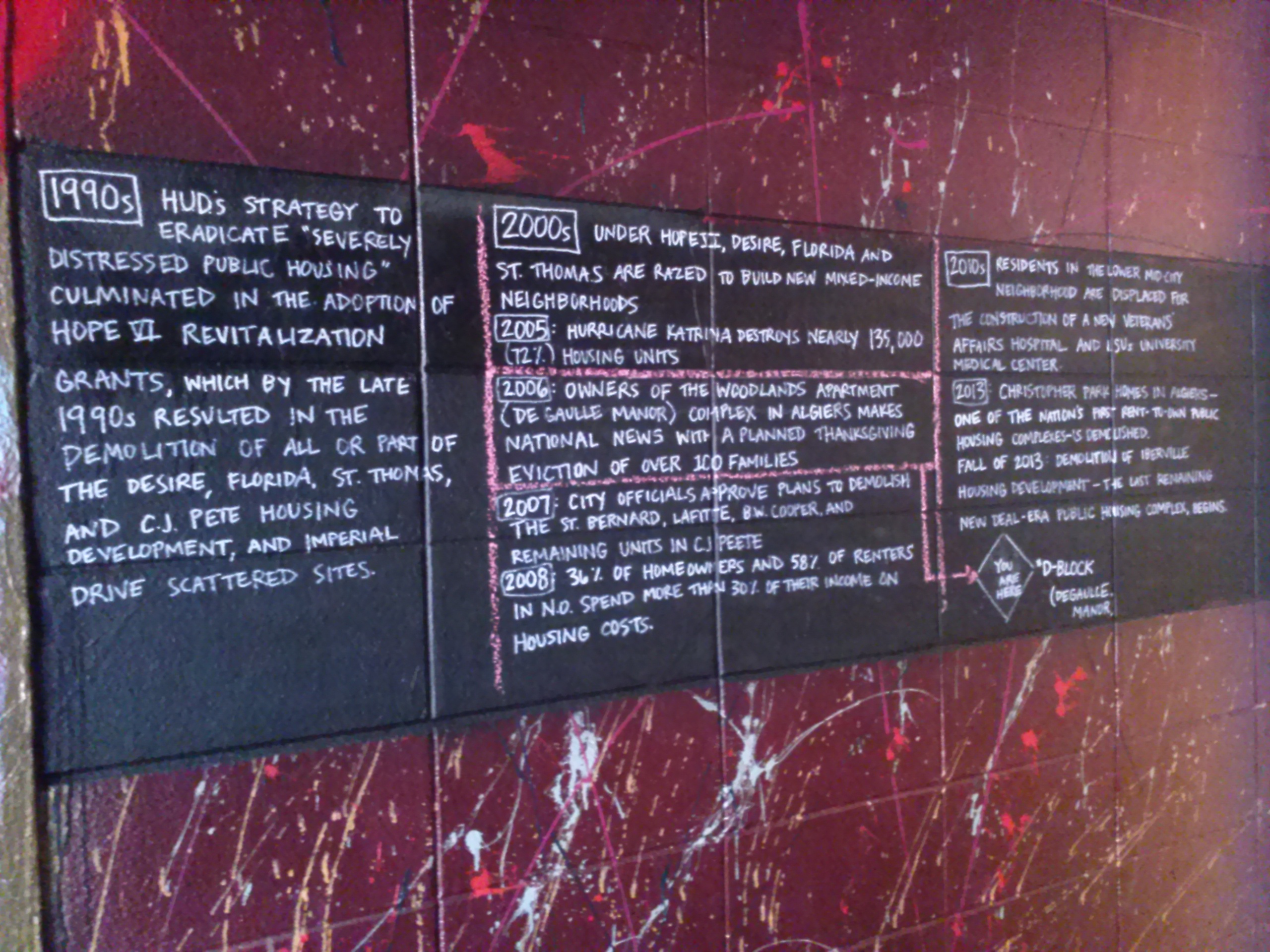

At ExhibitBE this past January, the New Orleans Wildseeds, the New Orleans chapter of the Octavia Butler Emergent Strategy Network, hosted an exhibit on displacement in New Orleans which stretched back to the 1930s and focused on the impact of segregation, gentrification, environmental upheaval, and more on black women and girls. “Sacred Space” honored:

“black children and their families who once called the DeGaulle Manor (the D-Block) home–and all those who have experienced housing insecurity, homelessness, and displacement. This interactive reimagined, multimedia altar installation makes use of found items [ninety percent]…engages historic and contemporary forms of discriminatory housing policies, displacement, and spatial segregation forced upon Black residents and low-income communities through an interactive timeline….”

The installation served as the entrance to the exhibit and the only to provide an explicit timeline that connected past and present upheavals and connect those to the vulnerability of women, girls, and families to displacement. The timeline, “Displaced: New Orleans” was researched and designed by Shana Griffin:

“DISPLACED asks: How do we not allow current strategies to eradicate blight become contemporary forms of urban renewal? How do we disrupt historical patterns of Black displacement and discrimination?”

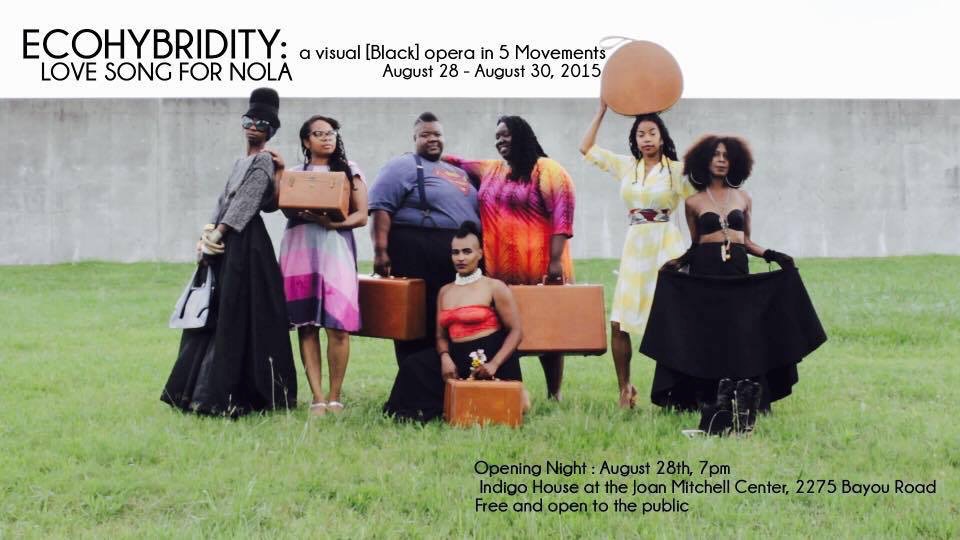

This grassroots, woman-driven insurgence continued this past August with EcoHybridity: A Love Song for NOLA. Sponsored by Gallery of the Streets (led by Kai Lumumba Barrow), EcoHybridity was a visual opera queer and trans featuring black women discussing environment, sustainability, and histories of insurgent reclaiming of space and self. From their IndieGoGo, EcoHybridity “marks the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina and examines issues connected to disaster capitalism, displacement, spatial inequities, the prison industrial complex, and the privatization of public resources from a Black feminist lens.” Watch the trailer here.

When the storm hit, the grim and cannibalistic reality was that an entire demographic of the population would be ignored, set aside, left behind, not out of outright animosity but because they’d been rendered completely invisible. To the powers that be. To social service entities. To everyone but themselves and the glare of news cameras who, voyeuristic and opportunistic as they were, made the spectacle of black suffering impossible to ignore–and yet black women, girls, queer people of color, families as a whole were ignored and continue to be. The declaration #SayHerName and #BlackTransLiberation even in the midst of an outpouring of attention in a movement declaring #BlackLivesMatter is a reflection of the same willingness to make the same mistake over and over. Render invisible. Forget, but forgetting as well that “when and where I enter” is the space to begin.

This past August, the truly breath-taking and brilliant Jeri Hilt published a time traveling, veil-crossing essay titled, “There Are No Survivors Without Scars.” In the voice of her grandmother, Jeri commands:

“Concede nothing, You alone own the reckoning. The world is a reflection of what YOU see, I beg of you namesake, look AGAIN. Write it as you would have it to be, and it will be so, in this life and the next.”

How do you remember a storm? DO “concede nothing.” What is “resilience” in the face of Katrina? What is survival in a black intellectual history of the New World?

And if there are to be black futures, DO NOT make the same mistakes over and over again. Black intellectual historians ignore what is happening around the memory of Hurricane Katrina and the archive it created at their own peril. New Orleans cannot be rendered invisible in our larger discussions of how and why black thought came to be–or what purpose it should serve.

*ExhibitBe, the largest free art installation in the South, was masterminded by black New Orleans artist Brandan ‘B-Mike’ Odums, held in the remains of the de Gaulle housing project in Algiers, and sponsored by Prospect 3 and the RDLN Foundation (which receives support from the wealthy and controversial Cummings family; John Cummings is the funder behind Whitney Plantation and Slavery Museum).

[Edited 2015 September 12 | 19:40:03 and 2015 September 13 | 09:57:40 to update information about the New Orleans Women’s Health Clinic, the Wildseeds installation at ExhibitBe and affiliated memberships. Thank you Shana Griffin for the corrections and detailed descriptions.]

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Has the information in this essay ever been presented to NPR, Public Television, The Washington Post, Atlantic Magazine, The New York Times, The Democratic Party, or 60 Minutes? NPR had a number of stories about the tenth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina most of which talked about the re-birth on New Orleans. They did actually review a book about the murders on the Danzinger Bridge. I understand that the US government poured a lot of money into New Orleans in the ten years since Katrina. Why hasn’t the Lower Ninth Ward rebounded like most of the other neighborhoods? Has New Orleans East been restored like the white neighborhoods? Are the levees in and around the city any taller? Why does the press describe NOLA as being a single bowl when it is really 6 saucers?

Hi Christopher. The information in this essay is drawn from the news sources you mentioned along with Slate, Gawker, The Times Picayune, the New Orleans Advocate, Pro-Public, City Lab, the New Orleans Defender, reports by the Newcombe Center at Tulane, and New Orleans community organization fact sheets all available online. Feel free to click the links above for more information that would answer some of your questions.

I’ve also posted and shared a number of articles relevant to Hurricane Katrina and New Orleans in general on the New Orleans Course Archive: nolacoursearchive.tumblr.com. Even more information is available there.

On the Danzinger Bridge – the best investigative reporting was done by ProPublica (linked in the post). They have an excellent “file” available online which outlines the case and evidence presented over the years.

The Lower Ninth Ward and other neighborhoods in the city have found it difficult to rebound due to a number of factors, including availability of housing, high rents, and individual owners’ inability to access funds made available after the storm (the Road Home program, for example). For more information on the lay of the land, the City Lab essay linked above has information on reports form all around the city. I’d also suggest the Greater New Orleans Data Center (http://www.datacenterresearch.org/) for more information. And I’d also caution the “most” — the displacement and return is more like pockmarks throughout the city than focused on one neighborhood like the Lower Nine (again, the City Lab essay outlines this very well and maps I’ve posted on the NOLA Course Archive can help add context as well).

To answer your final questions: The levees around the city are taller and deeper and why do YOU think the press describes New Orleans as 6 saucers? 🙂

Best, jmj

One more question: what is the name and title of the person who closed all of the old housing projects in NOLA after Katrina regardless of whether they were habitable or not? Was the decision made in Washington, D.C.? I ask these questions because I moved out of New Orleans nine months after Katrina because of loss of employment. I imagine that many of the answers to my questions can be found in the files of The Times-Picayune.

The decision was not made by any one person but was a HANO (Housing Authority of New Orleans) initiative that met a unanimous council vote. The vote, however unanimous, was not received well at all by members of those housing developments. Protests ensued at that same city council meeting. Protestors were tear gassed and arrested. There is still a huge amount of anger and frustration around the city’s decision today.

I am sorry for your loss of employment and am more than happy to respond to your curious questions, although you are correct, the answers are available in the TP files and elsewhere. I’ll direct you to where I can, for sure.

Where did you end up landing, after Katrina, if I may ask? I hope you’ve been well since.

Fantastic blog! Do you have any hints for aspiring writers?

I’m planning to start my own website soon but I’m a little lost on everything.

Would you suggest starting with a free platform

like WordPress or go for a paid option? There are so many choices out there that I’m completely overwhelmed ..

Any suggestions? Cheers!