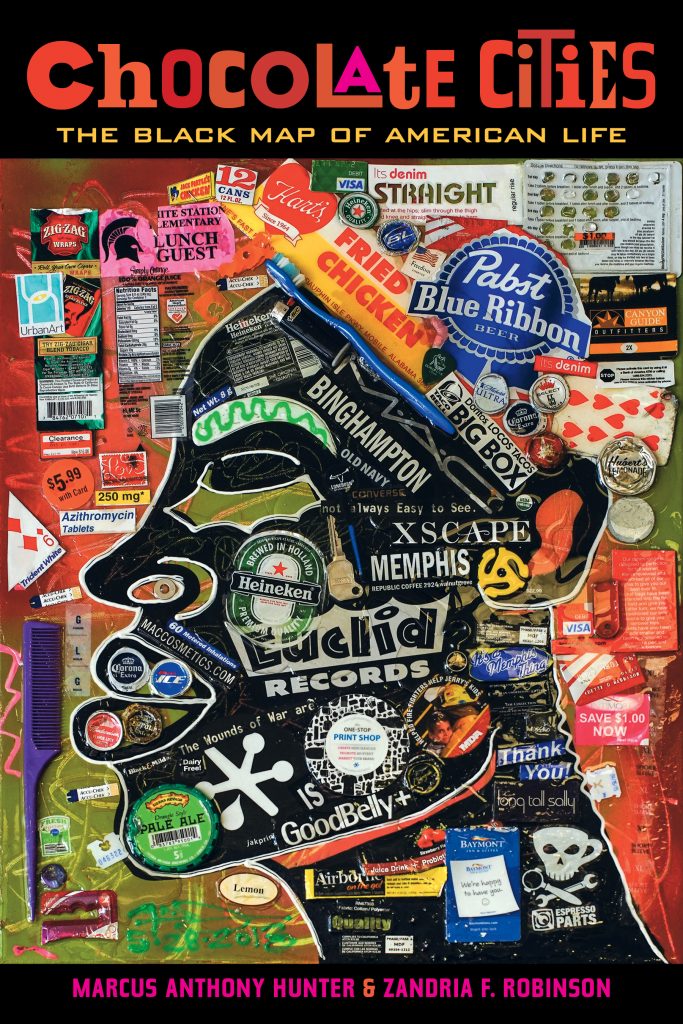

Chocolate Cities: A New Book on the Black Map of American Life

This post is part of our blog series that announces the publication of selected new books in African American History and African Diaspora Studies. Chocolate Cities: The Black Map of American Life was recently published by University of California Press.

***

The authors of Chocolate Cities: The Black Map of American Life are Marcus Anthony Hunter and Zandria F. Robinson. Marcus Anthony Hunter is Chair of the Department of African American Studies and Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he holds the Scott Waugh Endowed Chair in the Division of the Social Sciences. He is the author of Black Citymakers: How the Philadelphia Negro Changed Urban America (Oxford University Press) and the president of the Association of Black Sociologists. Follow him on Twitter @manthonyhunter. Zandria F. Robinson is Associate Professor in Rhodes College’s Department of Sociology and Anthropology. She is author of This Ain’t Chicago: Race, Class, and Regional Identity in the Post‑Soul South (University of North Carolina Press) and co-editor of Repositioning Race: Prophetic Research in a Postracial Obama Age (State University of New York Press). Follow her on Twitter @zfelice.

The authors of Chocolate Cities: The Black Map of American Life are Marcus Anthony Hunter and Zandria F. Robinson. Marcus Anthony Hunter is Chair of the Department of African American Studies and Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he holds the Scott Waugh Endowed Chair in the Division of the Social Sciences. He is the author of Black Citymakers: How the Philadelphia Negro Changed Urban America (Oxford University Press) and the president of the Association of Black Sociologists. Follow him on Twitter @manthonyhunter. Zandria F. Robinson is Associate Professor in Rhodes College’s Department of Sociology and Anthropology. She is author of This Ain’t Chicago: Race, Class, and Regional Identity in the Post‑Soul South (University of North Carolina Press) and co-editor of Repositioning Race: Prophetic Research in a Postracial Obama Age (State University of New York Press). Follow her on Twitter @zfelice.

From Central District Seattle to Harlem to Holly Springs, Black people have built a dynamic network of cities and towns where Black culture is maintained, created, and defended. But imagine—what if current maps of Black life are wrong? Chocolate Cities offers a refreshing and persuasive rendering of the United States—a “Black map” that more accurately reflects the lived experiences and the future of Black life in America. Drawing on film, fiction, music, and oral history, Marcus Anthony Hunter and Zandria F. Robinson trace the Black American experience of race, place, and liberation, mapping it from Emancipation to now. As the United States moves toward a majority minority society, Chocolate Cities provides a provocative, broad, and necessary assessment of how racial and ethnic minorities make and change America’s social, economic, and political landscape.

“A masterpiece! Chocolate Cities is a testament to the magic that is possible when you combine the funky wisdom of the Mothership with the best scholarship from the Ivory Tower.”— George Clinton, Rock & Roll Hall of Fame musician and founder of Parliament Funkadelic

J.T. Roane: What type of impact do you hope your work has on the existing literature on Black urban studies? Where do you think the field is headed and why?

Marcus A. Hunter and Zandria F. Robinson: Fifty years ago, the Kerner Commission report famously proclaimed that “our nation [was] moving toward two societies, one Black, one white–separate and unequal.” Commissioned in the wake of urban and rural Black rebellions in the long hot Civil Rights summers, its assessment of our broken democratic system powerfully noted what remains a central and enduring truth about this country. However, the report’s findings weren’t new to Black people who had always lived in a separate nation, a nation of Others not afforded the rights and protections guaranteed by our Constitution. Moreover, Black people had long thought about their place in the countries of their bodies, as writer James Baldwin would say, and the fact that they experienced an entirely different America. For example, four years before the report, James Baldwin’s 1964 documentary on Black life in San Francisco and American race relations “Take This Hammer” aired nationally. This extended visit and interviews with Black San Franciscans led Baldwin to a powerful conclusion. Adorned in a striped short-sleeved dress shirt and bright white ascot, Baldwin turned to the camera, eyes wide open, with a matter-of-fact tone: “Birmingham is just an incident. . . . What is very crucial is that the citizenry are able to recognize there is no moral distance, no moral distance—which is to say no distance—between the facts of life in San Francisco and the facts of life in Birmingham.” “This is the San Francisco America pretends does not exist,” Baldwin surmises. Baldwin’s observations provide clear and compelling evidence defying conventional wisdom about the relative differences between the North and the South, and the West and the South.

Indeed, much of the work produced by Black creative artists in the eras of Black Power and Black Lives Matter balances what Frankie Beverly and Maze named as “joy and pain”—from everyday policing to capricious, state-sanctioned murder to war—underscores an America where being Black is a minority status associated with a whole host of deficits and uniquely predisposed to all levels of violence. At the same time, in key moments, joy—dance, movement, bodily freedom—and highlight Blackness as a majority status associated with a whole host of assets. Together, these experiences of joy and pain give Black folks a unique predisposition—or a Cassandra’s curse—to offering the most honest assessment of whether or not this America, this whole country, is living up to its promise.

Chocolate cities—which we define as Black enclaves, neighborhoods, or what Zora Neale Hurston called “the black backside” of small towns, and other forms of Black community in public and private space—are disappearing across the country and often the sites of incidences where Black people are policed in public space embedding the notion in Black public consciousness. We argue, borrowing from the Black Christian tradition, wherever two or more Black people are gathered, there is a chocolate city. Demographically chocolate cities, like Washington D.C., are shrinking and reassembling across the suburbs and African diaspora. Black people feel them shrinking ever more with every re-zoning effort, new condo construction, smart growth plans, or cupcake shop. But chocolate cities still exist and are—once every blue moon—reflected on late night television. Black folks’ imaginings that different, more hospitable spaces, more equitable spaces are possible in America has helped us survive. Perhaps in being reminded that we have always created these spaces for ourselves, here, there, and everywhere, we can both survive and be liberated with this time’s fire.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

I have thought of Atlanta being a chocolate city.