Caribbean Federation and Black Diaspora Politics: An Interview with Eric Duke

This month, I interviewed Eric D. Duke about his new book, Building a Nation: Caribbean Federation in the Black Diaspora (University Press of Florida, 2016). The book is part of the interdisciplinary series, New World Diasporas, edited by Kevin A. Yelvington. Building a Nation examines the multi-sited debates over the creation of a regional federation in the British Caribbean. Drawing on sources from England, the Caribbean, and the United States, Duke argues that the idea of a regional federation connected reformers in the West Indies to Afro-Caribbean and other black activists and intellectuals in the diaspora. The project of building a federation, Duke contends, was deeply connected to global struggles in Africa and the African Diaspora for self-determination and racial uplift.

Dr. Eric D. Duke is Associate Professor of African American Studies, Africana Women’s Studies, and History at Clark Atlanta University. He completed his B.A. and M.A. at Florida State University and earned his Ph.D. in Comparative Black History from Michigan State University. Duke’s research specializations include Afro-Caribbean, African American, and African Diaspora histories. He is the coeditor of Extending the Diaspora: New Histories of Black People (University of Illinois Press, 2009) and has also published work in New West Indian Guide. He previously served on the advisory board of the Digital Library of the Caribbean and as past chair of the Caribbean Studies Committee of the Conference on Latin American History (CLAH).

Dr. Eric D. Duke is Associate Professor of African American Studies, Africana Women’s Studies, and History at Clark Atlanta University. He completed his B.A. and M.A. at Florida State University and earned his Ph.D. in Comparative Black History from Michigan State University. Duke’s research specializations include Afro-Caribbean, African American, and African Diaspora histories. He is the coeditor of Extending the Diaspora: New Histories of Black People (University of Illinois Press, 2009) and has also published work in New West Indian Guide. He previously served on the advisory board of the Digital Library of the Caribbean and as past chair of the Caribbean Studies Committee of the Conference on Latin American History (CLAH).

***

Building a Nation chronicles the effort to establish a federation among the islands of the English-speaking Caribbean from the turn of the twentieth century to the collapse of the West Indies Federation in 1962. In the book, you offer an intellectual history of the idea of federation as well as a social history of the campaign to create a unitary Caribbean nation. What led you to explore this topic?

Duke: With an interest in African Diaspora History, I began my doctoral studies intending to explore issues of “race and nation” in the Anglophone Caribbean. Initially, I assumed federation would simply be part of a general introduction to a project focused on Jamaica and Trinidad during the 1960s and 1970s. However, as I expanded my research I discovered the long history of support for a regional federation, which in many cases predated the idea of individual island independence. More importantly, I was excited to find clear connections between the push for a Caribbean federation—or the dream of a united West Indian nation—and larger black diaspora struggles during the first half of the twentieth century, including a fascinating but complicated history of race. Before long, this longer history of federation became my focus and a window through which I could explore issues of race and nation-building in the Caribbean.

In the first two decades of the twentieth century, proposals for federation emerged from two distinct groups: white “colonial power brokers” and Afro-Caribbean reformers. What did each group hope to achieve through the creation of a British Caribbean federation?

Duke: The idea of federation existed as early as the 17th century, but it’s not until the post-emancipation era that it really starts to figure prominently in discussions about the future of the Caribbean. As we know, the West Indies went from being considered by some one of the jewels in the British Crown to the “Empire’s darkest slum” by the turn of the 20th century. In line with support for federation projects in other colonies, the British imperial government reintroduced the idea of federation in the West Indies as part of a larger project to institute more efficient government.

The local white oligarchy in the Caribbean had historically been against federation. However, the economic crises of the late 19th and early 20th centuries convinced many to embrace federation as a means to institute some sort of economic cooperation and increased economic power. There was also some desire for a more efficient government, but in their case, they were more driven by their economic interests. Significantly, neither the local white oligarchy or colonial government viewed federation as an empowering project for the region’s black majority. It was a tool of colonial control. It meant instituting what I refer to as a “united status quo” with few changes to the existing economic, social, and political arrangements for the good of the West Indian masses.

For Afro-Caribbean reformers, both in the West Indies and beyond, federation was a means to pursue a variety of social and political reforms. While economic concerns were important, they wanted to gain some control over their lives and greater standing in their respective colonies. Broadly, Afro-Caribbean reformers fell into two groups. You have those who believed federation would happen whether or not the majority supported it, so they embraced federation. However, they were driven more by their individual “islandist” reform efforts, with some even looking to eventual individual island independence. In the second camp, there were others—like T.A. Marryshow, the father of Federation—who actually embraced and prioritized regional identification over island identification. For this group, a united West Indies was the ultimate goal rather than a step, and often tied more overtly to the global struggles of African and African-descended peoples. Despite some distinction, both of these groups viewed federation as a means to liberate and empower West Indian masses rather than upholding the status quo.

For Afro-Caribbean reformers, both in the West Indies and beyond, federation was a means to pursue a variety of social and political reforms. While economic concerns were important, they wanted to gain some control over their lives and greater standing in their respective colonies. Broadly, Afro-Caribbean reformers fell into two groups. You have those who believed federation would happen whether or not the majority supported it, so they embraced federation. However, they were driven more by their individual “islandist” reform efforts, with some even looking to eventual individual island independence. In the second camp, there were others—like T.A. Marryshow, the father of Federation—who actually embraced and prioritized regional identification over island identification. For this group, a united West Indies was the ultimate goal rather than a step, and often tied more overtly to the global struggles of African and African-descended peoples. Despite some distinction, both of these groups viewed federation as a means to liberate and empower West Indian masses rather than upholding the status quo.

As you can see, federation truly becomes the common answer to competing and conflicting interests.

In Building a Nation, you argue that West Indian activists in Harlem, London, and other “diaspora centers” played a crucial role in the federation movement. What are some specific ways that West Indians living outside of the geographic boundaries of the Caribbean contributed to the movement?

Duke: One of the most important contributions of activists living in diaspora centers (such as Harlem and London) is the very sense of being West Indian, the promotion of that regional identification. Numerous works have shown how people living in the diaspora—in North America and in London, as well as Central and South America, and elsewhere—often came to embrace a strong regional identification. While we cannot ignore those within the region who also embraced “West Indianness,” it was often beyond the islands that West Indian identification was more common and concrete.

And this was one of the most important issues driving my project. If “West Indians” largely existed outside of the region, then their views on a West Indian nation must be considered. In the book, I refer to West Indian activists based in the diaspora as “insiders outside.” There’s a temptation to act as if people living abroad have been away from the colonies too long to be actively engaged with or aware of politics “back home.” What does Richard B. Moore, W.A. Domingo, C.L.R. James, or George Padmore really know about Barbados, Jamaica, or Trinidad? When was the last time they’ve lived there? However, what we actually see is that many activists were in routine communication with activists and organizations in the region.

In these diaspora centers, West Indian activists connected the Caribbean freedom struggle to African American and African freedom struggles – struggles in which Afro-Caribbean activism has long played a crucial role. By aligning the cause of Caribbean federation with these larger anticolonial struggles, West Indians attracted significant publicity and support. In fact, at times the question of Caribbean federation was being argued and promoted among Afro-Caribbean and other black activists in places like London and Harlem more than in the region itself. While Harlem and London are not the only places where Afro-Caribbean activists are prominent, I argue in the book that these were two incredibly important diaspora centers.

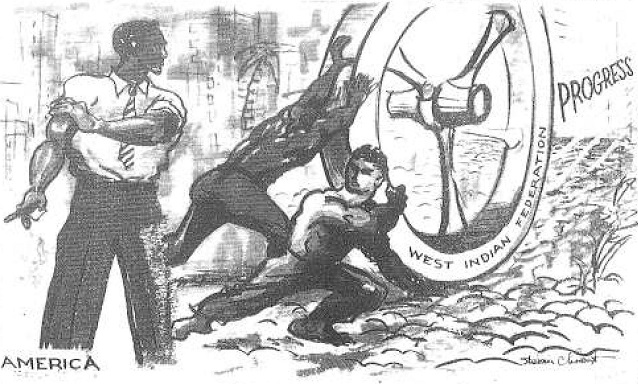

Political cartoon on the West Indies Federation, The West Indian American (April 1959)

Political cartoon on the West Indies Federation, The West Indian American (April 1959)

Also, West Indian leaders from the islands were routinely visiting these diaspora centers in the United States and England. They were meeting with a variety of both island and regional organizations and discussing the future of the West Indies, which quite often revolved around the idea of a federation. Furthermore, some of the organizations that came to prominence in the Caribbean—such as the Jamaica Progressive League (which developed strong ties to the People’s National Party), the Barbados Labour Party, and other groups were founded or heavily influenced by diaspora activists outside of the West Indies. So there was a steady flow of ideas between the region and these diaspora centers which not only provided moral and material support to the cause of Caribbean federation but often racialized the project and connected it to larger diaspora struggles – making it more than just a regional Caribbean project.

By the 1950s, as negotiations for a federation in the English-speaking Caribbean intensified, public debates about the possibility of a shared West Indian identity often focused on questions of race. In Chapter Four, you argue that several competing understandings of “West Indianness”—and the racial composition of the federation itself—emerged during this era. Tell us more about that.

Duke: Historically “West Indian” has been a rather fluid term. Initially, it was the label associated with white planters and merchants in the Caribbean. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, you see more and more an association of West Indian as a black identity. That’s largely because of the demographics of the region as a whole. Given the importance of the diaspora in the promotion of “West Indianness” this became even more profound. While there was not necessarily any sort of racial exclusivity in the redefinition of West Indian as black, there was certainly a hegemonic idea that the most authentic West Indian was someone who was of African descent.

In the Caribbean, activists did not always use overtly racial language. Some deemed it unnecessary, some sought to avoid drawing the ire of the colonial governments, and some certainly embraced a more multiracial creole nationalism. But in the diaspora, it was incredibly important to present federation as a project for racial empowerment and black liberation.

As you enter the post-World War II period and the long negotiations for a federation in the 1950s – when a West Indian nation moved from idea to pending reality – it became more pressing to define who is West Indian. At this time, one sees the British government—as well as even some activists who had previously spoken overtly in racial terms—turn more to Creole nationalism as a way to define “West Indian” as a multiracial and multiethnic identity. While racial and multiracial nationalism had long co-existed, at that point, their coexistence became more problematic. You also have the emergence of Indo-Caribbean politics in places like Trinidad and Guiana, particularly in the 1950s. Rather than risk racial strife, you do have some people pushing federation as a Creole nationalist project. So now ideas of “West Indianness” that had largely been so comfortably associated with blackness in the islands and in the diaspora suddenly becomes contentious. Finally, there was also a prominent resurgence of “islandism” over regionalism in some colonies in this era.

The West Indies Federation, established in January 1958 and dissolved in May 1962, highlighted the difficulties of creating a new nation among the many islands of the English-speaking Caribbean. How did Afro-Caribbean activists in the region and in the diaspora respond to the collapse of the Federation? How did the Federation’s demise affect the trajectory of black diaspora politics in the 1960s and 1970s?

Duke: We will never know what could have happened if the federation that many Afro-Caribbean activists wanted had even been instituted—one that was actually an independent nation with proper economic backing and politicians who set aside divisive matters until the nation got beyond its infancy.

Ultimately, when the West Indies Federation dissolved, reactions varied. In the colonies themselves, I think the long negotiations of the 1950s had somewhat prepared some for its possible failure. In the activist circles of the diaspora, many were distraught. Richard Moore and many of his Harlem allies were particularly upset over its failure, as were C.L.R. James, George Padmore, and others. Even Kwame Nkrumah bemoaned the loss of what he hoped would be a united black nation in the West. Many viewed the Federation’s failure as something that would haunt the region, and blamed the poor leadership of certain Caribbean politicians as well as the actual plan initiated. Of course, there was also some crucial opposition to the formal Federation from diaspora activists such as W.A. Domingo whose Jamaican nationalism fueled his opposition in this era. Overall, in the broader realm of black diaspora politics, the increasing number of independent nations appearing in Africa by the early 1960s, the immediate replacement of a colonial federation with the independent nations of Jamaica and Trinidad in 1962, and the possibilities of more to come, seems to have eased the disappointment of some who began to count the number of independent nations to denote progress.

As for the legacy of federation, the collapse of the West Indies Federation does not take away from the overall importance of this history. For me, as I really try to show in the book, the actual West Indies Federation is just one part of the longer history of the federation movement—not the central story. Given the continued debates over race and nation, connections to Africa and the diaspora, as well as the questioning of creole nationalism in the West Indies in subsequent decades, the broader story of federation is important.

While there continues to be periodic talk about federation in the Caribbean, a political union seems unlikely. Instead, what we see now in terms of regional unity are organizations like CARICOM, which are mostly confined to the economic realm. That was certainly not the dream of many who supported federation for decades.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

This was my introduction to the West Indies federation. I found the concept interesting but, nationalism forced it’s doom. It’s unfortunate because the more united, the more independent of US meddling.