Black Zionism, Reparations, and the “Palestine Problem”

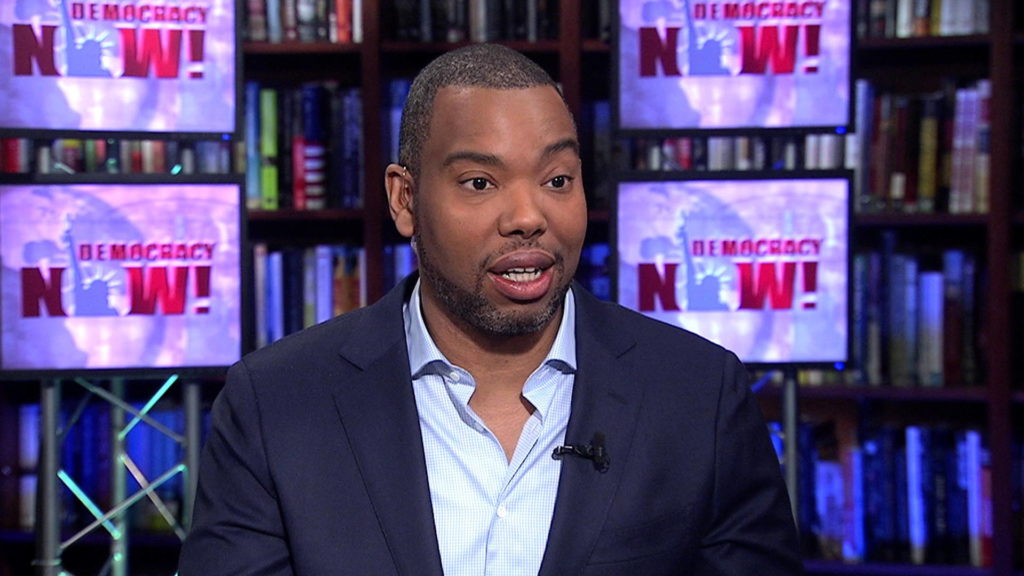

Earlier this year, Ta-Nehisi Coates made his now-familiar argument for reparations, which called for Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders to recognize the importance of racially-specific–rather than colorblind universalist–solutions to the legacies of slavery and racial discrimination. When Democracy Now! host Amy Goodman asked Coates about precedents for such reparations, he referenced the “grand precedent of the Holocaust,” citing the formation of Israel with financial subsidy from Germany.

Israel as a historical precedent for reparations is not new for Coates, and it stands in stark contrast to the recent framing for reparations by The Movement For Black Lives (M4BL), which instead cited contemporary calls for a Universal Basic Income (UBI) in Finland and Switzerland. In his George Polk award-winning article, “The Case for Reparations,” Coates argued that although reparations “could not make up for the murder perpetrated by the Nazis . . . they did launch Germany’s reckoning with itself, and perhaps provided a road map for how a great civilization might make itself worthy of the name.”

But this “road map” is a rocky one, evoked before by black intellectuals and activists ranging from Malcolm X and A. Philip Randolph to Stokely Carmichael and Ethel Minor. By invoking Israel as a precedent for reparations, Coates reminded me of Robin Kelley’s admonishment that “you cannot build a state on ethno-religious grounds.”

Interestingly enough, it is through the Nation of Islam (NOI) – a black nationalist group organized in part around ethno-religious grounds – that we can best trace the winding place of Israel in the black radical imagination. Long before the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, there was a Black Zionist tradition which envisioned the liberation and deliverance of those throughout the African diaspora using the book of Exodus.

The story of the Israelites’ emancipation from bondage in Egypt, led by the prophet Moses to the promised land of Canaan served as a blueprint for black nationalists ranging from David Walker, Henry McNeal Turner, and Martin Delany to Marcus Garvey, Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, and Rastafarians. As Kelley notes in Letters to Palestine: Writers Respond to War and Occupation, Black Zionism provided “not only a narrative of slavery, emancipation, and renewal, but with a language to critique America’s racist state since the biblical Israel represented a new beginning.”

But there was also the precedent of U.S. settler-colonialism in the name of African American repatriation through the emergence of Liberia. Liberia was a product of both white and black American interests. The American Colonization Society, supported by Abraham Lincoln and other prominent politicians, began sending freed black volunteers to Liberia in 1822. The African Civilization Society, founded by Henry Highland Garnet in 1858, supported emigration to the West Indies, Mexico, and Liberia.

However, in both cases, Americo-Liberians, as African-American settlers became known, took control of indigenous West African land. Local people were excluded from citizenship until 1904. Liberia also supported U.S. business interests, and in order to exploit cheap labor reached a deal in 1926 with Firestone Tire and Rubber Company. The agreement was a triangular pact: Firestone would produce rubber, the Liberian government would receive military protection against hostile neighbors, and the U.S. government would gain a coveted naval post off the coast of West Africa. A last-minute clause dictated that the Liberian government would take a $5 million dollar loan from Firestone, effectively putting it under control of the U.S. government. The case of Liberia reveals how the pathways of American capitalism and neo-colonialism rerouted black freedom dreams. The Black Zionist vision of a liberated homeland became a settler-colonial state characterized by an exploitative ruling class, natural resource extraction, and a U.S. military outpost.

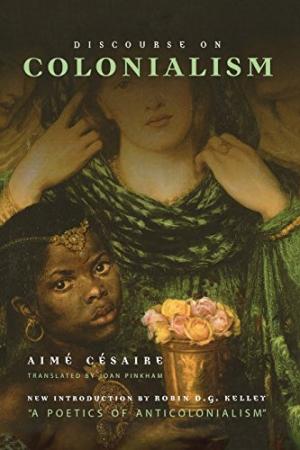

When Israel was founded in 1948, most black intellectuals did not see the state in settler-colonial terms, but rather as a nationalist effort which responded to the genocide of the Holocaust. Aimé Césaire’s Discourse on Colonialism (1950) pointed out that the Holocaust itself was a form of colonial violence. A. Philip Randolph called the establishment of Israel a “heroic and challenging struggle for human rights, justice, and freedom.”

When Israel was founded in 1948, most black intellectuals did not see the state in settler-colonial terms, but rather as a nationalist effort which responded to the genocide of the Holocaust. Aimé Césaire’s Discourse on Colonialism (1950) pointed out that the Holocaust itself was a form of colonial violence. A. Philip Randolph called the establishment of Israel a “heroic and challenging struggle for human rights, justice, and freedom.”

The most conventional marker of the shift in black radical thinking about Israel coincided with the Arab-Israeli War of June 1967 (also known as the Six-Day War or the June War), when the Central Committee for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) commissioned a report on the conflict. Published in the SNCC Newsletter, the essay “The Palestine Problem” established a critical stance on Israel as a litmus test for black radicalism and internationalism. However, the development of that critique had its origins in the nearly two-decades of shifting discourse within the NOI on whether or not to consider Israel an important historical precedent to buttress its claims for reparations and a separate state, or to denounce it as anti-Arab settler-colonialism.

On one hand, Jewish Zionism supported the NOI’s claims for land in the United States and acted as an important model for statecraft. At his first major college address at Boston University’s Human Relations Center in 1960, Malcolm X identified Israel as a historical precedent for reparations and a black state. Even as late as May 1964, after he had left the Nation of Islam and made Hajj, Malcolm advocated learning from the “strategy used by the American Jews” and suggested that “Pan Africanism will do for people of African decent [sic] all over the world the same that Zionism has done for Jews all over the world.”1

But a closer look at the ways in which the NOI mobilized Israel in a discourse of reparations shows that throughout the 1950s, the NOI developed an anti-Zionist language to understand the relationship of Israel to the Arab world. As scholar C. Eric Lincoln prepared his dissertation on the Nation, he noted that “Anti-Zionist doctrine is just now becoming a part of overall temple propaganda. [Ahmad Zaki El] Borai and Bashir are working closely with Malcolm X on a long-term project including the importation of a group of dark-skinned Arab-propagandists. Arabs are frequently in touch with E[lijah] in Chicago according to [Abdul Basit] Naeem.”2 This was a direct outcome of the NOI’s interaction with the emerging nonaligned movement, which did not see Israel as part of its struggle against global imperialism and colonialism.

To the contrary, in 1956, Israel was on the side of Britain and France in the invasion of Egypt under President Gamal Abdel Nasser. The following year, Egypt hosted the first Afro-Asian Peoples’ Solidarity Conference and Elijah Muhammad sent a telegram of support noting its importance to his “long lost brothers of African-Asian descent here in the West.”3 Members of the NOI even hung portraits of Nasser in their homes.

Even in Malcolm’s speech at Boston University, he hardly endorsed Israel as much as used it as leverage in demands for land:

The United States can subsidize Israel to start a state – Israel hasn’t fought for this country. The United States can subsidize India and Latin America – and they tell the Americans to ‘go home!’ We even subsidize Poland and Yugoslavia and those are Communist countries! Why can’t the Black Man in America have a piece of land with technical help and money to get his own nation established? What’s so fantastic about that?4

However, it was his 1964 essay in the Egyptian Gazette, “Zionist Logic,” which extended the linkages between Israel and American interests the furthest. The incisiveness of Malcolm’s essay is likely due to his visit earlier that year to the Khan Yunis refugee camp in Egypt and his meeting with PLO president Ahmed al-Shukairy. He positioned Israel as a “new form of colonialism,” arguing that Zionism had no legal or religious basis and was simply colonialism camouflaged though philanthropy and economic aid to developing nations. He also made the important link to political economies and charged that “zionist dollarism” drove 20th century imperialism. As opposed to the “African-Arab Unity under Socialism” prescribed by Nasser, the United States and Israel crippled emerging independent African nations through capitalism and militarization.

When SNCC published “The Palestine Problem” three years later, Stokely Carmichael claimed it was an opportunity to test its leadership in the “form of sharp questions against a background of incontestable historical facts.” The document listed thirty-two facts regarding Palestine intended to educate those in the organization rather than offered as a position paper.5 But although the essay’s author, Ethel Minor, claims it was merely intended to lay out an “objective critique of the facts,” her background suggests an interest in its policy implications as well. Minor was a former Chicago schoolteacher who had lived in Colombia, South America before returning to join the NOI.6 She left when Malcolm X split in 1964, becoming secretary of the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) that summer.7

Although she moved back to Chicago, Minor continued to be close with Malcolm X and met with him a month before his death.8 While Minor was likely also influenced by her closeness to Palestinian students in college, her critique of Zionism also drew from her time in the NOI and OAAU.9

![The Palestine Problem [Garrett Felber]](https://cdn.aaihs.org/2016/08/The-Palestine-Problem-Garrett-Felber.png) The question is not simply whether or not to support reparations. There is ample moral justification and empirical evidence to suggest reparations are at least one-hundred and fifty years overdue. And, as historian N.D.B. Connolly points out, Coates’ call to support Rep. Conyers’ HR 40 – an $8 million proposal to study the impact of slavery and racial segregation – makes sense as a starting point. But, he importantly adds that we should “question additional attempts to substitute expert consultation and elite-run committees for more forceful attacks on segregation, lynch law, and mass incarceration.”

The question is not simply whether or not to support reparations. There is ample moral justification and empirical evidence to suggest reparations are at least one-hundred and fifty years overdue. And, as historian N.D.B. Connolly points out, Coates’ call to support Rep. Conyers’ HR 40 – an $8 million proposal to study the impact of slavery and racial segregation – makes sense as a starting point. But, he importantly adds that we should “question additional attempts to substitute expert consultation and elite-run committees for more forceful attacks on segregation, lynch law, and mass incarceration.”

We should also be wary of how we choose our historical precedents for reparations. While the M4BL platform clearly defines Israel as an “apartheid state,” what remains glaringly absent from Coates’ analysis is the internationalism which provided the backbone for radical rejections of Zionism. To use the establishment of Israel as a “grand precedent” misses the important intellectual labor and evolution of black thought from the 1950s-1970s on the relationship of Israel to larger structures of capitalism, imperialism, and neo-colonialism. When using a historical “road map” in calls for reparations, we should ensure the map highlights the insights and contributions of black radicals and internationalists.

- “Malcolm X Makes it Home From Mecca,” Amsterdam News, May 23, 1964. ↩

- Race Doctrines,” handwritten notes, no date, Box 136, Folder 8, C. Eric Lincoln Collection, Robert W. Woodruff Library, Archives Research Center, Atlanta University Center. ↩

- “Mister Muhammad’s Message to African-Asian Conference!” Pittsburgh Courier, January 18, 1958. ↩

- Malcolm X, quoted in C. Eric Lincoln, The Black Muslims in America (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), 92. ↩

- Clayborne Carson, “Blacks and Jews in the Civil Rights Movement,” in Strangers and Neighbors: Relations Between Blacks and Jews in the United States, eds., Maurianne Adams and John Bracey (Boston: University of Massachussetts Press, 1999), 582-583. ↩

- Ethel Minor, “An African American Tells Why She Followed Malcolm X,” in Oh Freedom! Kids Talk about the Civil Rights Movement with the People Who Made it Happen, eds., Casey King and Linda Barrett Osborne (New York: Random House, 1997), 94-96. Accessed May 23, 2016, http://herb.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/963. ↩

- OAAU FBI File, Summary Report, New York, September 23, 1964, 29 and OAAU FBI, Director to Chicago, Memorandum, March 3, 1964. ↩

- OAAU FBI File, Director to Chicago, Memorandum, February 18, 1965, 2. ↩

- Carson, “Blacks and Jews in the Civil Rights Movement,” 582 and Radosh, Divided They Fell, 31. ↩

![Zionist Logic [Garrett Felber]](https://cdn.aaihs.org/2016/08/Zionist-Logic-Garrett-Felber.png)