Black Women’s Suicide and a Call for Radical Friendship

I am still sitting with the loss of Ashawnty Davis, the 10-year-old Black girl from Aurora, Colorado who ended her short life this past November. After a video of Ashawnty fighting with another girl, whom Ashawnty’s parents identified as her bully, was posted online, Ashawnty hanged herself–unable to handle the exposure. She died in a hospital after two weeks on life support. She had not lived long enough to know how much her decision would devastate others or that her possibility, passion, and pain could be cherished. She had yet to truly discover how she was and could be loved, and in turn, how she might live.

Ashawnty’s suicide was called a “bullycide” in the media. The conversation around bullying has amplified in recent years as cases of young people taking their own lives dramatize and draw attention to violence among and expressed by children. According to the Centers for Disease Control, suicide is the tenth leading cause of death in the US and while enacted at a higher rate by older demographics, in 2014, it was also the second leading cause of death among kids between the ages of ten and fourteen. A 2015 study found a significant increase in suicides among Black children, specifically Black boys, and a decrease among white children, raising new questions about the racial undercurrents of suicide.

In the US suicide not only expresses itself differently by age group, but also by gender and race. American Indians and Alaskan Natives and white (non-Hispanic) people present the highest rates of suicide of all racial or ethnic groups. By contrast the rates of suicide among Black people are seventy-percent lower than white (non-Hispanic) populations. Men are more likely to die by suicide than women, whereas women make more attempts. This is consistent with Black women who attempt suicide at rates higher than Black men and lower than white women. Although there is inconsistent and limited national data on suicide attempts writ large, The National Black Justice Coalition found that nearly half (forty-nine percent) of Black transgender respondents from a 2015 survey reported attempting suicide. Respondents spoke to the extreme isolation and violence experienced in the matrix of transphobia, anti-Black racism, misogyny, patriarchy, and poverty. They conveyed how social oppression and exile have suicidal consequences for Black people.

Black women are outliers. They have the lowest rates of suicide in the nation, posing what is called “the black-white suicide paradox,” the assessment that Black women should manifest rates at least equivalent to their white and non-white counterparts. Researchers attribute the paradox in part to possible misclassification. Yet the numbers remain low and Ashawnty’s death does not alter these statisics. Whether high or low, Black girls’ and women’s statistics in the US rarely gain much attention when not serving the role of further evaluating or assessing Black boys or men or corroborating the broad category of girls’ or women’s suffering. In the case of Ashawnty, her death garnered attention as a child suicide and as a case of bullying; it did not trigger a conversation about the troubles of Black girls. Statistics do little of the qualitative work necessary to deepen a social understanding of Black girls’ and women’s self-destructive as well as self-sustaining behaviors.

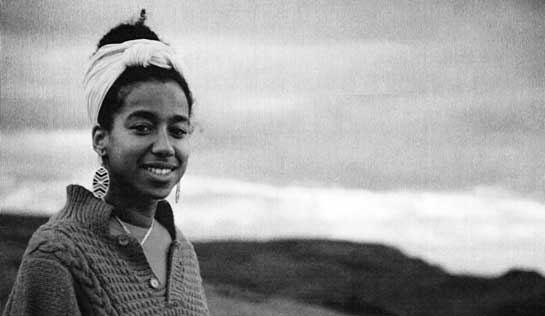

In lieu of statistics, I turn to the story of the Afro-German poet, activist, and scholar May Ayim who took her life at age thirty-six across the Atlantic in Berlin-Kreuzberg. In 1996, she jumped from a high-rise building leaving a written legacy of the anatomies of racial hurt. Born to a Ghanaian father and white German mother, May was orphaned and raised by a white foster family. Her writings document her troubles in a family and a country from which she felt alienated, and at times abused, because they failed to understand her Blackness. The intimate themes of her poetry dialogued with her socio-historical analyses of the Black presence in Germany and its diasporic reaches. In her poem “Blues in Black and White,” which shares the same title as her 1995 collection of poems, she writes,

1/3rd of the world unites

against the other 2/3rds

in the rhythm of racism, sexism, and anti-semitism

they want to isolate us; eradicate our history

or mystify it to the point of

irrecognition

it’s the blues in black-and-white, it’s the blues.

May taught and raised consciousness about Black German and European experiences through her art, scholarship, and activism. In her 1996 poem “what does a life do to die,” May asks, “how many soul wounds does a heart need for the plunge into stillness?”1 Already with a broken heart, May’s verse tells of her waning desire to live. May’s friends corroborated her slow disappearance. A period of intense work led to a psychosis and eventually a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis that compounded her psychological collapse and gave way to a suicide attempt and hospitalizations. Nourished and guided by Audre Lorde and her Black Feminist collective vision, May nevertheless, experienced profound isolation as her friends loyally stood by. Neither her poetry nor the movement she helped found provided ample relief.

Feeling unknown equals a process of disappearance, and Black women’s suicide in a strange way illuminates how little is truly witnessed or palpated about Black women’s living: of being poorly compensated for often uninspiring work, for being assessed in destructive and shaming numbers, overlooked in thought and vantage, and emotionally unregistered. Disappearance is both a figurative and a literal metaphor, especially when it comes to Black women. Joyce Vincent was a thirty-eight-year-old Black British woman who died alone in her London apartment with her skeletal remains discovered in 2006, almost three years after her estimated death. Explored in the 2011 documentary Dreams of a Life, her disappearance poses an exacting question about how her absence went so terribly unnoticed and un-pursued at the same time that Black women gain social attention for every misstep. These are the haunting paradoxes of Black women’s lives and deaths.

Scholars who take Black women’s suicidal behaviors and voices to heart suggest that Black women’s faith, social networks, and devotion to others may prevent them from taking their lives. Relationships that couple support with understanding, underlie and energize what may be otherwise referred to as resilience; and Black women’s friendships play a poignant role in this meditation on suicide. At times resiliency intones a positive attribute, a capacity to withstand the hardest of circumstances. But this word association overlooks the racial, gendered, and economic structures that have required Black women to be emotionally, physically, and psychically durable in the face of whatever comes. Industriousness can rewrite the sense of will and perseverance that, while admirable, compel Black women to face incredible pressures, which tend to manifest in health problems, not often instantly fatal, but weathering them into disappearance. Black women’s resilience contributes, and beautifully so, to their low suicide numbers, but it masks their vulnerability. For those who keep on, less is known about what they fear, what is missing, and what they desire. For Black women and girls like Ashawnty who end their lives, we will never know what they wanted and did not request.

I speak of this heavy-hearted topic to initiate a conversation on friendship. May’s life and passing, her poetry and activism, existed within a world and movement of Black women. A leader in her own right and a student of Audre Lorde’s transformative presence and thought, May engaged a community of Black women, diasporic in scope. Her writings and publication emerged out of collaborations with other Black women, and their linkages evolved a concept of “radical friendship,” the focus of a future essay.

Ashawnty Davis probably had friends, but we heard mainly about her bullies. Her loss focuses us to become clearer on the necessity of robust friendship and how its absence starves people. Black women who end their lives should provoke conversations about both destructive and coping behaviors, interminable external pressures and the practices, including friendship, that shore up a life. May Ayim’s suicide does not overshadow her body of work or her contributions. How Black women like May sustain themselves remains as necessary a conversation as the circumstances that lead to their deaths. I hope Ashawnty’s story kindles such dialogues.

- Silke Merti. “Blues in Black and White: May Ayim (1960–1996),” in May Ayim, trans. Anne Adams, Blues in Black and White: A Collection of Essays, Poetry and Conversations (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2003), 143. ↩