Black Women’s Holy Ghost Work: Then and Now

“East Harlem leaves had the red tips of early autumn when Amaryllia (Lillie) Jones ventured down E. 131st Street in 1919 to her neighbors’ home for worship services. Addie and Edward Anderson and Ida and James Burleigh had opened their shared brownstone to sojourners from the Midwest—Robert C. and Carrie F. Lawson—who had come to New York to spread the fire of the Pentecost. Exactly how Lillie heard about the gathering is not part of the historical record. Perhaps she was friendly with the Burleighs and Andersons. Maybe she heard the praises to the Lord as she walked by; it was only a block from her home. Lillie joined the worshippers and gave her life to Jesus that same year, being baptized in the East River and baptized in the Spirit—speaking in tongues ‘as the Spirit gave them utterance’ (Acts 2:4).”1

The promise of embodied spirit power attracted Lillie Jones and other Harlemites, mostly women, to the Lawson’s services, which soon outgrew the brownstone. They opened the “Gospel Tent” at the corner of 144th St. and Lenox Avenue, and within a matter of months purchased property at 52-54-56 W. 133rd Street, naming it The Refuge Church of Christ.

Today, nearly one hundred years later, Refuge is known as Greater Refuge Temple. It continues as an overwhelmingly female Harlem-based church, housed in a former Loews Theater at 127th Street and Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard. Refuge Temple can accommodate three thousand attendees and is mother church to the denomination The Church of Our Lord Jesus Christ of the Apostolic Faith, Inc. (COOLJC, pronounced cool-JC), which has grown to nearly 500 churches across the US and Caribbean. The promise and experience of spirit power and gifts of the Spirit—speaking in tongues, divine healing, miracles, prophecy, and discernment—continue as the heart of the church community.

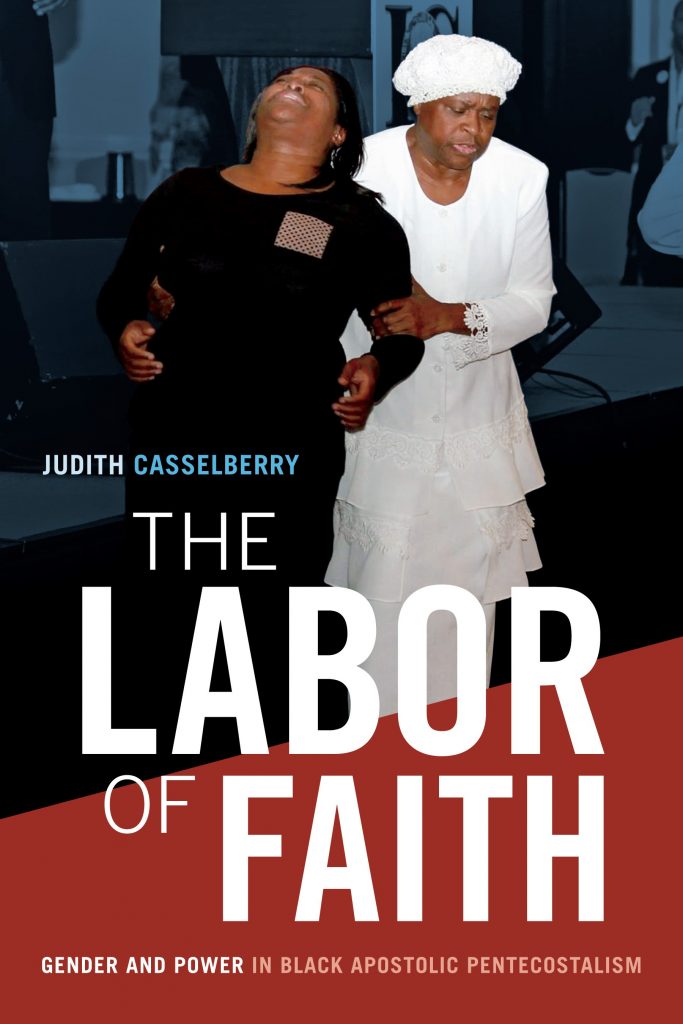

From COOLJC’s inception up to the present day, Black women have undergirded the denomination spiritually and financially. As one of the oldest historically Black Pentecostal denominations in the United States, this male-headed organization only functions through the work of churchwomen, who despite making up three-quarters of active adult membership, hold no formal lifetime positions of power. My ethnography, The Labor of Faith: Gender and Power in Black Apostolic Pentecostalism (Duke University Press 2017) delves into the ways in which the women of COOLJC, through spiritual and material labor, negotiate power relations in order to (re)-produce a holy Black womanhood and community in a late-twentieth and early twenty-first century context.

The approach of this study is unique in that it does not seek to connect the work of these Black holy women to civic or political activism. Rather it brings my two and a half years of immersion in the church into conversation with Black feminist religious historians and feminist labor theorists to examine the contours and full extent of churchwomen’s labor regardless of any discernible political outcomes in the wider Black community. When African American women’s religious work is viewed through the lens of civic and political work the nuances of spiritual labor and spiritual authority can be obscured.

COOLJC women’s commitment to “letting the Holy Ghost lead and guide” informs the ways in which they identify, exercise, and hone skills necessary for building and sustaining a spirit-filled self and community. In addition to fundraising and organizational and material labor through auxiliaries, COOLJC women perform emotional, intimate, and aesthetic labor across a range of sites to sustain the church.

Emotional or relational labor is complicated by working in the context of a church that is both a quasi-familial structure and a corporate institution. Further, navigating systems of church authority that privilege both spiritual power and male-headed hierarchy extracts emotional labor from women when their spiritual authority and male leadership are at odds.

I was inadvertently caught up in one such public moment as a participant in the Bible study class for unsaved and newly saved attendees. Minister Anderson, the Superintendent of Sunday school, directed me to move to another class, as he wanted to add numbers to that group. He told me in the presence of the class and the instructor Mother England. As he walked away, she told me (in a voice the class could hear), “Don’t worry about that. You come back here next week. I’ll let him know.” Slightly annoyed she went on, “You don’t belong over there. He should know that.”

Mother England was concerned with the spiritual development of the students in her charge. I was not saved and should not graduate out of her class. I did not witness the behind the scenes negotiation, but returned to Mother England’s class as she had instructed. Minister Anderson did not bring the move up to me again and our relationship stayed intact. In moments like these, women deftly practice strategies such as “leading from behind” to accomplish their goals while leaving the “women-driven patriarchy” in place.

One significant arena of church work that has developed under women’s control is altar work—guiding people through spiritual rebirth and into full inclusion in the church community. While ministers (men) do pray for souls to come to Jesus, the intergenerational network for training and reproducing a holy-ghost filled community is in the hands of women. Their intimate labor, which pulls together and intensifies reproductive and caring work, builds the institution spiritually and financially by bringing in new members.

Altar workers use specific intimate verbal and bodily language to guide seekers into a new spiritual life. One altar worker, Mother Grayson explained, “You’re there to encourage that person. You know, [and here her tone became blanket-like, soft and warm] press your way. I know you can do it. Say Jesus.” The sounds, intimacy, power, and exertion of altar work are associated with women.

Importantly, saints (as the saved refer to themselves) most often recall the presence and persistence of the church mother or missionary woman who guided them to Spirit infilling. Altar workers would “stay all night long” if necessary. “When I was seeking the Holy Ghost,” one saint recalled, “it didn’t matter how long you stayed. [It was] somewhere between one and four in the morning when I got saved.”

As the overwhelming majority of active members, women are also central in (re-) producing and transmitting the aesthetics of the church milieu. Women perform aesthetic labor that links material and spiritual realms to manifest the “beauty of holiness.” Materially, doctrine is codified most rigorously on women’s bodies through dress regulations that prohibit sleeveless tops, pants, and skirts above the knees and require stockings and head coverings in the sanctuary. Dressing “according to the standard,” a woman presents herself as an “ambassador for Christ” with all the attendant spiritual authority, and the church relies on her sounding body in worship to make the invisible (spirit) visible (embodied). Given that women are in the majority and that Spirit infilling is egalitarian, the religious bodies of COOLJC women most often actualize the “anointing.”

Spiritual authority and the character of female power within a male-headed hierarchy anchor my inquiry into churchwomen’s labor. With this first sustained ethnographic study of Black American Apostolic Pentecostal women, I hope to shed light on the particularities of these women’s religious labor—the work they do; how they do it; the circumstances under which they carry it out; and the benefits to the self, the community, and the institution.

In 1912, Maggie Lena Walker, a public intellectual, labor activist, and entrepreneur, and the first Black woman bank president asked, “How many occupations have Negro Women? Let us count them: Negro women are domestic menials, teachers and church builders.” Walker places the effort and outcome of women’s religious labor in its proper context. Recently, Sister Addie Thomas put it this way: “[T]he women are the ones pushing the church and lifting, and everything, doing most of the stuff.”

But most women church builders, then and now, also hold down paid jobs and raise families. Yet, scholars have failed to analyze Black women’s church work as labor in its own right. The Labor of Faith seeks to fill that gap. Without understanding the full extent of Black women’s labor in the church, we cannot grasp the entirety and meaning of Black women’s work writ large.

- Judith Casselberry, The Labor of Faith: Gender and Power in Black Apostolic Pentecostalism (Duke University Press, 2017), 45. For details about the East River baptisms of the early church, see Alexander C. Stewart and Sherry S. DuPree, editors, “Interview with Mother Hattie Banks, March 12, 1991 by Alexander C. Stewart, transcription by Mrs. Elaine McQueen.” In The Silent Spokesman: Bishop Robert Clarence Lawson, Founder of the Church of Our Lord Jesus Christ of the Apostolic Faith, Inc., New York City (Gainesville, FL: Displays for Schools, 1994). ↩

Great read! Our History as Women of Color has paved the way for where I am today. I am so thankful for the Labor of Faith & Love in Jesus name!