Black Women’s Fugitivity in Colonial America

Lucia, a fourteen-year-old young girl transported to the Georgia Lowcountry during the 1760s, brought with her a deft understanding of her provenance. Prior to her forced migration, her father established her identity by placing “a black stroke over each of her cheeks” as a mark of her ethnicity. Her family’s conception of their historical reality no doubt included reverence for naming ceremonies, secret societies, and the rituals associated with such societies, gendered roles, warrior traditions, and untrammeled freedom. For Lucia, who escaped in November 1766, running away was the final act of resistance to enslavement. It was a Pyrrhic Victory against a system that sought to subsume her traditions and knowledge of herself. Within this system of inhuman bondage, however, enslaved Africans such as Lucia retained a sense of themselves and relied on an informal network of both enslaved and free Africans for support, including the quasi maroon communities developed by Africans who escaped enslavement.

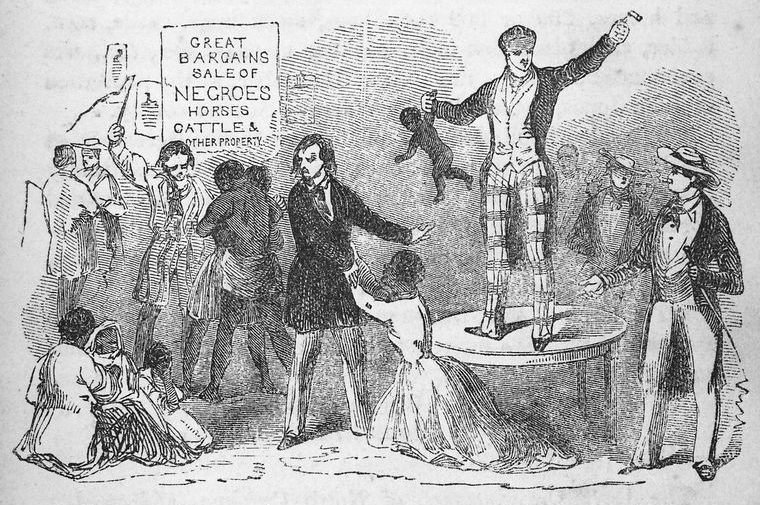

Enslaved women and girls ran away as soon as they set foot in the Americas. Some escapes were collective, others were individual. While some newly arrived women escaped immediately, others did so within a few weeks of arrival and others escaped months later. On June 16, 1733, fifteen-year-old Juno arrived on the slave ship Speaker in Charleston, SC. She had arrived from Angola along with 316 other enslaved men and women (out of 370). Two weeks after being sold to a planter from Dorchester, she escaped. Colonial Black resistance in the form of self-emancipations constituted forms of abolitionism. In “mining the forgotten” women and girls who appear in runaway slave advertisements, historians recover Black resistance in the form of truancy and escape as central components of abolitionism. In her study of abolitionism, The Slave’s Cause, Manisha Sinha has advanced new perspectives on Black abolitionism that challenge the idea that white philanthropy and free labor advocates were responsible for the abolitionist movement. Key to her book is the argument that “slave resistance, not bourgeois liberalism, laid at the heart of the abolitionist movement.” Sinha revives the early perspectives advanced by scholars such as C.L.R. James and Benjamin Quarles who viewed the runaway slave as the “self-expressive presence [without whom] antislavery would have been a sentiment only.”1

As discrete communities based on shared transatlantic pasts, slave societies in America were linked by regional origins, American destinations, and New World cultural developments. Throughout the New World, enslaved Africans perceived themselves as part of a community that had distinct ethnic and national roots. Randomization was not a function of the Middle Passage. Although slave ships traversed the coast of Africa to secure Africans, in some instances, slave ships also drew their cargo from only one principal port. These ports included Gorée, Bonny, Calabar, Elmina, and the Biafra ports. Slave ships bound for Georgia included captive Africans who shared a similar linguistic heritage, for example, Mande speakers such as the Malinke and Soninke. To a large extent, the transatlantic Middle Passage in the North Atlantic defined and shaped African perceptions of kinship, ethnicity, and community.

The Middle Passage can be characterized as a space of “in betweeness” with its links to the origins of captive Africans. As a voyage through death, the Middle Passage paradoxically asserted life through its destructive process. Through the marginal spaces of slave ships, captive Africans forged bonds of kinship and created forced transatlantic communities under desperate conditions. Captive Africans such as Lempster, James, Peter, Fanny, and Silvia, who may have arrived on the same slave vessel, survived the Middle Passage and labored on the Georgia rice plantation of James Read. Identified as Gola slaves, they maintained ethnic and kinship ties through their forced migration, settlement, and collective escape from slavery. The ethnic and cultural make-up of the African supply zones for the Georgia Lowcountry in the late eighteenth century included the Fula, Igbo, Gola, and Mande speakers such as the Malinke, Bambara, and Mende.2

The advertisements for escaped Africans reveal acts of strategic resistance, central to the expression of human agency in bondage. Illustrative of this is Ben and Nancy, both twenty-five years old, who escaped their enslavement on James Read’s rice plantation in early December 1789 by crossing the Ogeechee River with several other captives. Prior to their escape, Ben and Nancy, who was blind in one eye, had married. Their marriage and their plans to escape slavery by making their way to Spanish settlements in Florida underscored the determination of enslaved Africans to subvert slavery and the structures and powers that perpetuated the system. Like Ben and Nancy, Patty and Daniel (of William Stephens Bewlie’s rice plantation) planned to escape slavery by running away to Spanish Florida. Nine months earlier, Patty had given birth to a son, Abram. Wearing a green wrapper and coat, and carrying additional clothing with which to change, Patty carried her son through the swamps of the Ogeechee neck in route to Florida and freedom.

Invariably, women fugitives sought out a town as the place to pursue diverse objectives for running away. Savannah and the outlying areas of the city proved an opportune environment for runaways. In Sunbury, Georgia, a “negro girl, 16 years old and Guiney born,” escaped from the Ogeechee River ferry enroute to Savannah still wearing handcuffs. Similarly, Sally and her two mulatto children found refuge in the woods near Savannah as their owner, Alexander Wylly, promised severe prosecution to any person harboring or concealing them. From the 1730s to 1805, one out of five runaways, or eighteen percent, were women.3

In several instances, newly arrived Africans saw enslavement as a problem to be solved collectively. On June 20, 1779, 36 Africans, twelve of them women, ran away from their enslaver Benjamin Edings on Edisto Island, South Carolina. Proximity to rivers and other bodies of water facilitated escape as runaways usurped canoes to make their escape. For newly enslaved Africans, planning an escape involved utilizing networks on the plantation. These networks centered on shared occupations as well as shared origins. On Mark Carr’s plantation near Sunbury, Bridgee, a “prime sawyer,” who spoke fluent Portuguese and Spanish, organized other sawyers on the Carr plantation. He also included his wife Celia in his plans to escape slavery. After inflicting “several outrages” near the ferry, the group cut away a chained canoe at the Sunbury wharf and made their escape northward. In October 1780, a plea came from John Rose of Savannah for the apprehension of three male slaves and three female slaves, which included “a girl of fifteen years.” One of the women, Phebe had five children with her with “one of them at the breast.” The other, Juno, had two children with her.

Resistance represented a formative process which involved a tension between what the enslaved thought and what they lived. Runaway slave advertisements provide a window for examining the thought and aspirations of enslaved Africans. In this context, the act of running away marked the establishment of a dialectical relationship with the environment in which captive Africans lived. An examination of 270 advertisements for runaway slaves, reveal that 126 advertisers designated fugitive Africans by nationality and included detailed descriptions of country markings. Sydney, a young woman whose country marks were evident on her breast and arms, and who spoke “no English,” took flight from the home of Elizabeth Anderson, well dressed with a cloth gown and coat. Like many other new Africans, Sydney was unfamiliar with the environment in which she lived. She envisioned a successful flight from the oppression of bondage in the city and deftly concealed her country marks and her identity as a fugitive as she moved through the city of Savannah.

Newspaper advertisements help to map fugitive women’s and girls’ geographies, detail their individual stories, and go to the very reason for attempted escape. Tracing the movement of enslaved women and girls in, out, and through spaces in colonial America as well as the Atlantic world through runaway advertisements provides insight into Black women’s agency.

- South Carolina Gazette, July 21, 1733; Slave Trade Database, Speaker, VIN 76714 (accessed 03/16/2019); Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolitionism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016); C.L.R. James, “The Atlantic Slave Trade and Slavery,” in John A. Williams and Charles F. Harris eds., Amistad Vol. I, (New York: Random House, 1970), 142. ↩

- Georgia Gazette, July 13, 1774, James Read, in Lathan Windley, Runaway Slave Advertisements, Vol. IV, 53; Elizabeth Donnan, Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade, vol. 4, (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1930), 612-663; The Transatlantic Slave Trade Voyages Database, accessible at www.slavevoyages.org, see entries for Georgia. The notices for runaways in this article are from Windley’s, Runaway Slave Advertisements, Vol. IV. ↩

- Michael Mullin, Africa in America: Slave Acculturation and Resistance in the American South and British Caribbean, 1736–1831, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press), 290. ↩