Black Women, the Nation of Islam, and the Pursuit of Freedom

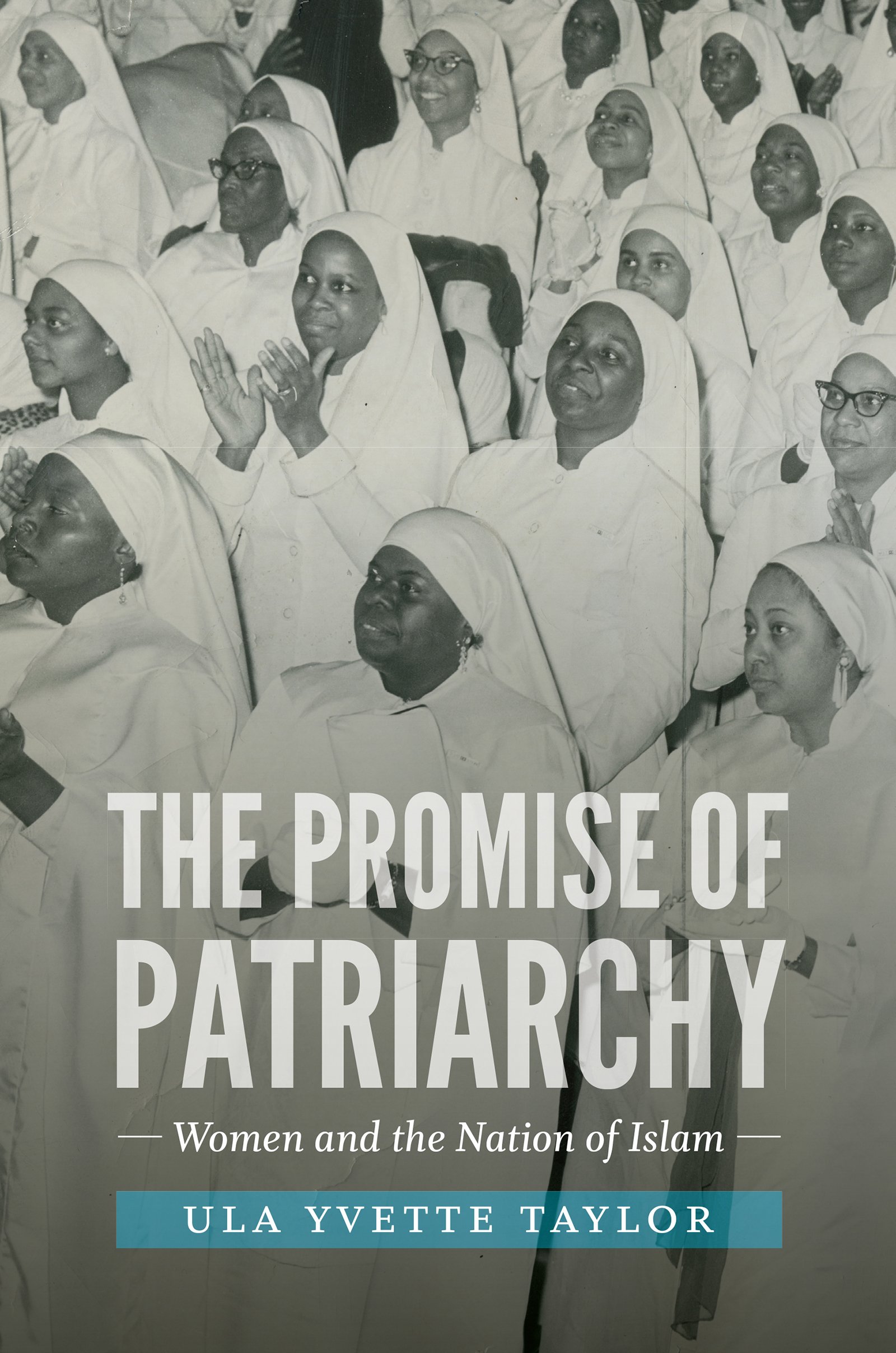

This post is part of our online roundtable on Ula Taylor’s The Promise of Patriarchy

Ula Y. Taylor stands as one of today’s leading scholars of African American women’s history, Black nationalism, and the African diaspora. Her seminal first book, The Veiled Garvey: The Life and Times of Amy Jacques Garvey, examined the ways Pan-African activist Amy Jacques Garvey of Jamaica combined feminism and nationalism to empower Black women and uplift African-descended people globally. Taylor’s newest book, The Promise of Patriarchy: Women and the Nation of Islam explores the multidimensionality of Black women and their pursuit of freedom in a masculinist Black movement.

Exhaustively researched and beautifully written, The Promise of Patriarchy looks at the complex ways Black women in the Nation of Islam (NOI), the largest African American Muslim organization of the twentieth century, pursued freedom and dignity through a Black nationalist group that fiercely upheld the masculine roles of protector and provider. Taylor terms this gender politics “the promise of patriarchy.” She highlights the importance of women like Clara (Poole) Muhammad, Burnsteen Sharrieff, and Ethel Sharrieff to advancing the NOI’s goal of building an autonomous Black nation. The author looks at these women’s lives within the larger historical context of the Great Migration, World War II, the Cold War, the Civil Rights-Black Power movement, and the women’s movement. In doing so, Taylor challenges prevailing scholarly narratives that have focused on high-profile NOI male leaders like W. D. Fard, Elijah Muhammad, and Malcolm X. The author neither apologizes for the group’s masculinism nor romanticizes Black women’s experiences in the NOI. Instead, she tells a “powerful narrative of resilience and resistance; a story of unapologetic love and the conscious choice to be remade for the larger good of the black race” (6).

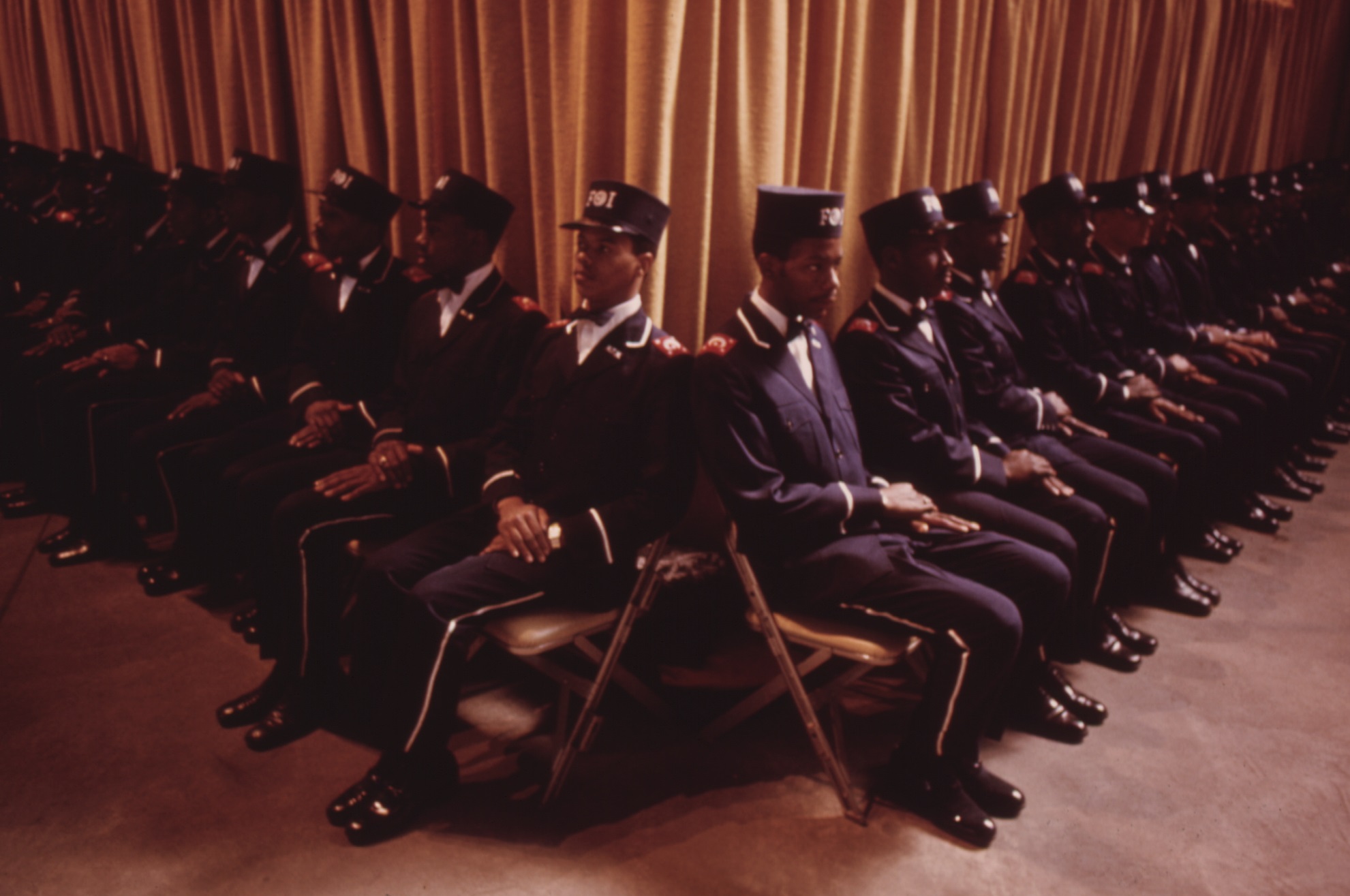

Recovering the significance of women like Clara Muhammad to the making of the Nation of Islam constitutes one of Taylor’s most important interventions. The standard narrative of the Nation’s formative years focuses on W. D. Fard. An enigmatic figure, he founded the NOI in Detroit in 1930. Claiming to be from Mecca, Fard preached that Islam was the true religion of the “Asiatic Blackman,” denounced white people as “devils,” and promoted racial separatism. Above all, he called on Black people to remake themselves into self-reliant, racially proud people. Promoting the Black nuclear family was a centerpiece of his teachings. Fard institutionalized this vision through NOI auxiliaries the Fruit of Islam (FOI) and the Muslim Girls’ Training and General Civilization Class (MGT-GCC). The FOI instructed men to provide for and protect their wives and families, while the MGT-GCC taught women to master the domestic sphere.

Fard’s message captured the imaginations of recently arrived African American working-class southern migrants, who had fled the Jim Crow South in search of a better life in the urban North. However, many of these newly arrived southern migrants encountered new and more virulent forms of racial oppression in places like Detroit. Following Fard’s mysterious disappearance in 1934, his lieutenant Elijah (Poole) Muhammad emerged as the Nation’s new leader and moved the group’s headquarters to Chicago. By the early 1960s, Elijah Muhammad headed the most influential U.S. Black nationalist organization.

Taylor convincingly shows how “what became the Nation of Islam was driven by a woman”—Clara Muhammad (14). Sister Clara, as she was known in the NOI, was critical to introducing her husband, Elijah Muhammad, to the teachings of W. D. Fard. Her interest in the Nation emerged out of concern and frustration with her husband’s inability to provide and protect his destitute family in Depression-era Detroit. He suffered from alcoholism and could not hold a job. In search of a better life, Sister Clara found W. D. Fard and went to NOI meetings without her husband. Upon her urging, Elijah eventually attended NOI meetings, befriended Fard, quit drinking, and enlisted in the organization. Converting to Islam changed the couple’s lives. They remade themselves through adopting NOI beliefs and discarding their “slave name” Poole for Muhammad.

In the coming years, women like Sister Clara, Burnsteen Sharrieff, Ethel Sharrieff, and Christine Johnson “anchor[ed]” the Nation. Burnsteen Sharrieff served as Elijah Muhammad’s loyal secretary in the NOI’s formative years. Sister Clara and Pauline Bahar played a crucial role in keeping the Nation alive during World War II after federal authorities indicted and incarcerated Elijah Muhammad for subversion. Uplifting Black women and children was a crucial component of women’s work within the NOI. Sister Clara, her daughter, Ethel Sharrieff, and Christine Johnson directed much of their attention to administering the University of Islam, NOI-affiliated parochial schools whose curriculum promoted the organization’s beliefs and an African American-centered education. In addition, Taylor discusses the courtship and marriage of Betty Shabazz and Malcolm X as a way to appreciate the private lives of a high-profile Nation couple.

One of the book’s most interesting discussions looks at the appeal of Black nationalism and the promise of patriarchy to Nation women in the 1960s and 1970s. Taylor carefully situates her subjects’ willingness to embrace modesty, marriage, and motherhood at a moment when the vast majority of Black women toiled in low-wage service jobs and when negative cultural representations of Black womanhood abounded. Plus, civil rights reform failed to significantly improve the lives of the Black urban poor. Given this context, the prospects for dignity, protection, economic prosperity, nation-building, and personal fulfillment through modesty, marriage, and motherhood made sense to Nation women. Taylor draws these conclusions from extensive interviews with current and former NOI members like Khalilah Ali (Belinda Boyd), the first wife of Muhammad Ali, the poet Sonia Sanchez, and civil rights activist Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons.

At the same time, Taylor shows how Nation women sometimes “trumped” NOI patriarchy by defying their husbands and the organization. Some women worked outside of the home against their husbands’ wishes. Others divorced their husbands, which NOI rules allowed. Some Nation women practiced family planning, defying the Nation’s staunch opposition to contraception. The marriage of Khalilah Ali and heavyweight champion boxer Muhammad Ali (Cassius Clay) offers interesting insight into the ways Nation women sometimes trumped patriarchy. Skillfully negotiating her husband’s ego and gendered expectations for her role as a wife, she managed his finances and public appearances without fundamentally challenging her husband’s role as head of the family. This move provided Khalilah Ali with a degree of control over her life and marriage, but ultimately her actions reaffirmed patriarchal power.

Although Taylor highlights the potential promise of patriarchy for Nation women, she does not overlook the ways masculine leadership subordinated them within the larger organization. She emphasizes how the exaltation of Black woman by Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X, and other NOI male leaders often “helped camouflage the gender inequalities in the NOI with the affectionate rhetoric of love, protection and respect for black womanhood” (161). Even though they praised Black women, Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X often denounced African American women for their alleged immorality. Nation men sometimes physically and sexually abused their female partners. Taylor’s discussion of Elijah Muhammad’s sexual infidelities and fathering of numerous children with several of his young secretaries speaks to one of the most egregious examples of sexism within the NOI. Taylor is sensitive to the emotional pain Sister Clara surely felt from her husband’s actions. However, the author does not judge Sister Clara for remaining publicly silent about her husband’s infidelities. While women claimed important space within the NOI, patriarchal oppression lived on in the organization.

More broadly, Taylor’s book contains important lessons for understanding contemporary African American gender politics. For more than forty years, Black feminist and queer activists and thinkers have articulated powerful critiques of the pitfalls of heteronormativity. State violence against and the continued marginalization of Black women and LGBTQ people of color, as well as Black intra-racial sexual violence, remain serious issues. Yet the promise of patriarchy continues to resonate among a significant portion of Black America. The Million Man March of 1995 led by NOI leader Louis Farrakhan is a case in point. Calling for Black men to atone for and to take responsibility for their alleged failures as fathers, spouses, and leaders of their communities, the march in essence promoted patriarchy as the fulcrum for Black American freedom. Millions of African American women supported the march’s call because they believed that empowering Black men as providers and protectors would invariably improve the lives of Black women and their communities. After reading The Promise of Patriarchy, one can gain a better sense of how we arrived at our contemporary moment. The book’s brilliance and usefulness rest in Taylor’s critique of this politics and her appreciation for the complicated ways Black women—then and now—have sought to liberate themselves and their people. For these reasons, The Promise of Patriarchy is a must read.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.