Black Women, Slavery, and Silences of the Past

Power does not enter the story once and for all, but at different times and from different angles. It precedes the narrative proper, contributes to its creation and to its interpretation . . . In history, power begins at the source.”—Michel-Rolph Trouillot

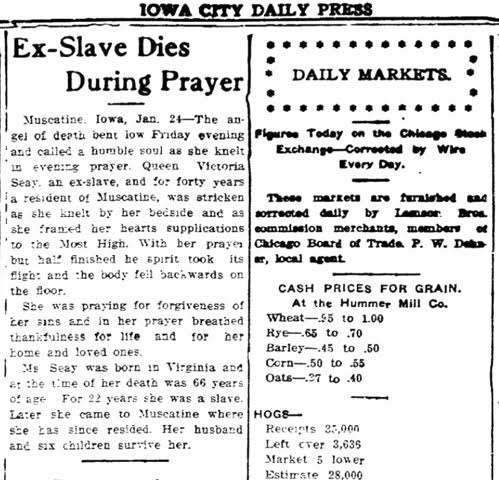

On Monday, January 24, 1910, the Iowa City Press Citizen presented its readers with a curious headline: “Ex-Slave Dies During Prayer.” The ensuing article, situated just to the left of the daily markets, proclaimed that the

angel of death bent low Friday evening and called a humble soul as she knelt in evening prayer. Queen Victoria Seay, an ex-slave, and for forty years a resident of Muscatine, was stricken as she knelt by her bedside and as she framed her hearts (sic) supplications to the Most High. With her prayers but half finished the spirit took its flight and the body fell backwards on the floor.

She was praying for forgiveness of her sins and in her prayer breathed thankfulness for life and for her home and loved ones.

Ms. Seay was born in Virginia and at the time of her death was 66 years of age. For 22 years she was a slave. Later she came to Muscatine where she has since resided. Her husband and six children survive her.

Placing her obituary beside the price for wheat offered at the Hummer Mill Co., the Press-Citizen treated Queen Victoria in death as slaveowners had regarded her in life. It commodified her, selling its version of her narrative just as local farmers did their grain.

A narrative is not truth, though. And the Press-Citizen did more to silence than elucidate Queen Victoria’s life and death.

Born during the late 1830s, Queen Victoria spent the first twenty or so years of her life in Virginia.1 Both of her parents were Afro-Virginians, as was Julius Seay, an enslaved man with whom she had romantic ties. I am unsure whether she lived with her parents or if their master(s) separated them. Moreover, I am uncertain whether Queen Victoria and Julius worked on the same plantation or if theirs was an abroad marriage.2

Still, one thing is clear: Queen Victoria was enslaved but she was never a slave. One newspaper later reported that she “escaped through the underground railway to Canada and lived there until after the [Civil] war when she settled in Muscatine.”3 According to Seay family lore, that newspaper was partially right—whatever ties that Queen Victoria had to Virginia were too weak to keep her there. But that lore never mentions help from abolitionists. Instead, they maintain that Queen Victoria freed herself and later returned to liberate Julius. Militancy is at the heart of those stories. It is embodied by a Seay heirloom—the rifle that Queen Victoria once carried with her to ward off slave catchers.

Given those acts of self-emancipation and abolition, it is unsurprising that Queen Victoria made the most of her freedom. During Reconstruction, Queen Victoria reclaimed a given name that was likely meant to mock her enslaved status. She and Julius also legally married and raised two children in Albemarle County, Virginia before moving to Muscatine, a city that was once a haven for fugitive slaves and had since become a home for thousands of freedmen and women. There Queen Victoria chose not to work. Instead, she maintained the Seay household while Julius farmed.

By 1900, the Seays owned that home.4 They achieved not only freedom but also an independence that would shape the family for generations to come. Besides renting rooms in their home to black and white boarders, Queen Victoria and Julius raised four more children, including Walter Lemuel. Queen Victoria, who had learned how to read and write, made sure that Walter and his siblings attended school and received the education denied to enslaved people. In turn, Walter gave a love of education to his son, George Liston. George Liston then passed that love on to his daughter, Joanne LeVonne.

And I am grateful that she then passed it on to me, her son.

There is an obvious discrepancy between these two narratives about Queen Victoria. In accordance with the “faithful slave” trope so intertwined with Lost Cause ideology, the Press-Citizen characterized Queen Victoria as a “humble soul,” a religious “ex-slave” in the same mold as Harriett Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom. Moreover, the Press-Citizen assigned her an age (66) and number of years spent enslaved (22) that conveniently placed her date of emancipation after the Civil War. White readers who still possessed what David Blight calls an “emancipationist vision” of the Civil War could thus assign the Union Army credit for Queen Victoria’s freedom. Her militancy was silenced.

My alternative narrative about Queen Victoria departs from those fictions. It suggests that Queen Victoria resisted bearing children during slavery. That childlessness might have made her escape more viable. After making the decision to run (a decision typically more available to enslaved men) Queen Victoria returned to liberate Julius. Those actions help us understand her later choice to join countless other freedwomen and refrain from menial labor. They also encourage us to see her favorite song—”Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”—as evidence that her spirituality was inseparable from her rebelliousness. My Queen Victoria worshipped a God who demanded resistance.

These discrepancies illustrate what anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot called the “cycle of silences.” According to Trouillot, silences enter the process of historical production on four overlapping occasions: the creation of sources, archives, narratives, and history. The Press-Citizen illustrates that point. It retrieved a number of “facts” about Queen Victoria’s life while creating new ones about her death. It assembled those old and new “facts” into a narrative that made a number of historical claims. Those claims then demonstrate that power, so intertwined with white supremacy, is the greatest determinant of when and where those silences enter.

Ultimately, black intellectual history exposes and usurps that power. It melds black folklore and archival sources, in the process undermining assumptions about historical knowledge and practice that reproduce racist ideologies. It also accepts a once-enslaved woman as a historical actor engaged in the production of ideas, thus shattering definitions of “the intellectual” that reinforce social hierarchies. In doing both, black intellectual history gives voice to those who most deserve to be heard.

It erases the silences of our past.

Brandon R. Byrd is an assistant professor of history at Vanderbilt University and working on a book manuscript entitled, An Experiment in Self-Government: Haiti in the African-American Political Imagination. Follow him on Twitter @bronaldbyrd.

- Her grave lists her birth date as May 10, 1841. But that date ranges from 1837 to 1847 in other sources. A birth date in the late 1830s most closely matches oral and written histories in which her self-emancipation predates the Civil War. ↩

- There were several slaveholding Seays in Virginia. For instance, Austin Seay and his son were two of the largest slaveowners in Amelia County. See 1860 U.S. Federal Census—Slave Schedules, Amelia County, Virginia, National Archives and Records Administration, M653, database online (http://www.ancestry.com; last accessed September 20, 2016). ↩

- “Colored Woman is Summoned at Prayer,” newspaper clipping, undated, from Seay family records. ↩

- 1900 Federal Census, Muscatine, Iowa, p. 20b, National Archives and Records Administration T623, digital reproduction, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com; last accessed September 20, 2016). ↩

Thank you for this article. It is deeply appreciated. This is crucial American history.

Thank you for reading! I wanted to take this opportunity to also highlight a productive exchange with a fellow #Blktwitterstorian who pointed out the problems inherent in the phrase “[she] maintained the Seay household while Julius farmed.” I see how a “just” is implied in that phrase and in a previous sentence that equates work with paid, masculine labor in a capitalist economy. A less rushed and more accurate analysis would better engage with the work of gender and slavery scholars including Jacqueline Jones and reaffirm the ways in which Queen Victoria *did* continue to work and define self-determination for herself and for her family.

excellent point raised and equally excellent reply. and when I lived in Clinton, Iowa, in about 1957, in 9th grade, there were two black families there. I shared a locker with Malvina, I believe her name is. She welcomed me and helped me get oriented- part-way into the school year, and we didn’t stay long. My dad worked for DuPont and we moved frequently. There was a boy our age also, from the other black family. I wonder now and then if they ended up marrying – both great kids, were a “date” on the one hay ride we all took, but would they have met other black families? (and we’re assuming here, given the times, that marrying outside of the black community was quite literally unthinkable). I’ve tried over and over to remember Malvina’s last name, to try a search, but can’t even be sure I have her name right – time takes a toll. But Malvina comes to mind, and how she was smiling and warm. Maybe someone can fill this in a bit.

Thank you so much for this article. I live for these golden nuggets of our history. We indeed were a mighty people!

From the poet Mari Evans:

I am a black woman

the music of my song

is written in a minor key

and I

can be heard humming in the night

Can be heard

humming

in the night

Thank you for this article. It give a inside piece of my family tree and somewhat of who I am where my family name begin end originated.

What a wonderful article; thank you for taking her history back.

Impressive story of a strong woman. I enjoyed reading it.

A really inspiring story-great. Thank you.