Black Women Doctors in the World of Comics

This guest post is part of our blog series on Comics, Race, and Society, edited by Julian Chambliss and Walter Greason.

Black women’s progress often collides with media stereotypes about them. However, media can also contradict these stereotypes. Crystal Emery’s 2016 documentary, Black Women in Medicine, highlights stories of successful black women doctors. Black actresses who portray doctors on fictional television shows, such as Grey’s Anatomy’s Chandra Wilson and How To Get Away With Murder’s Corbin Reid, also have the potential to inspire women to join the medical industry. If these manifestations did not exist in our media, young black women might not view medical careers as viable options. As Dr. Jocelyn Elders, the first black United States’ Surgeon General, said to filmmaker Crystal Emery, “You can’t be what you can’t see.”

Yet, even when a black woman earns the credentials required to become a physician, racial and gender biases still cause others to look at her with skepticism when she introduces herself as a doctor. Dr. Tamika Cross experienced this during a flight to Houston and she shared the details of that encounter on Facebook. In response to her post, the hashtags #TamikaCross and #WhatADoctorLooksLike propagated throughout social media as more doctors began sharing similar incidents.

The racism and sexism seen today are the latest chapter in more than 150 years of discrimination against black women pursuing medical careers. Rebecca Davis Lee Crumpler became the United States’ first black woman physician in 1864. Decades later, W.E.B. Du Bois penned the 1933 article, “Can a Colored Woman be a Physician?”,which responded to its title with a resounding “yes” by chronicling the career of Dr. Virginia Alexander. Yet, almost a century after its publication, many still question black women’s medical credentials.

The inability to see black women as doctors extends into the world of comic book superheroes. Doctor Strange, Beast, and Professor X are just a small sampling of the many white superheroes who are also doctors. However, it is difficult to find a similar list for black super heroines. Fortunately, Dr. Cecilia Reyes can be found in the pages of Marvel’s X-Men–introduced by writer, Scott Lobdell, and artist, Carlos Pacheco in 1997.

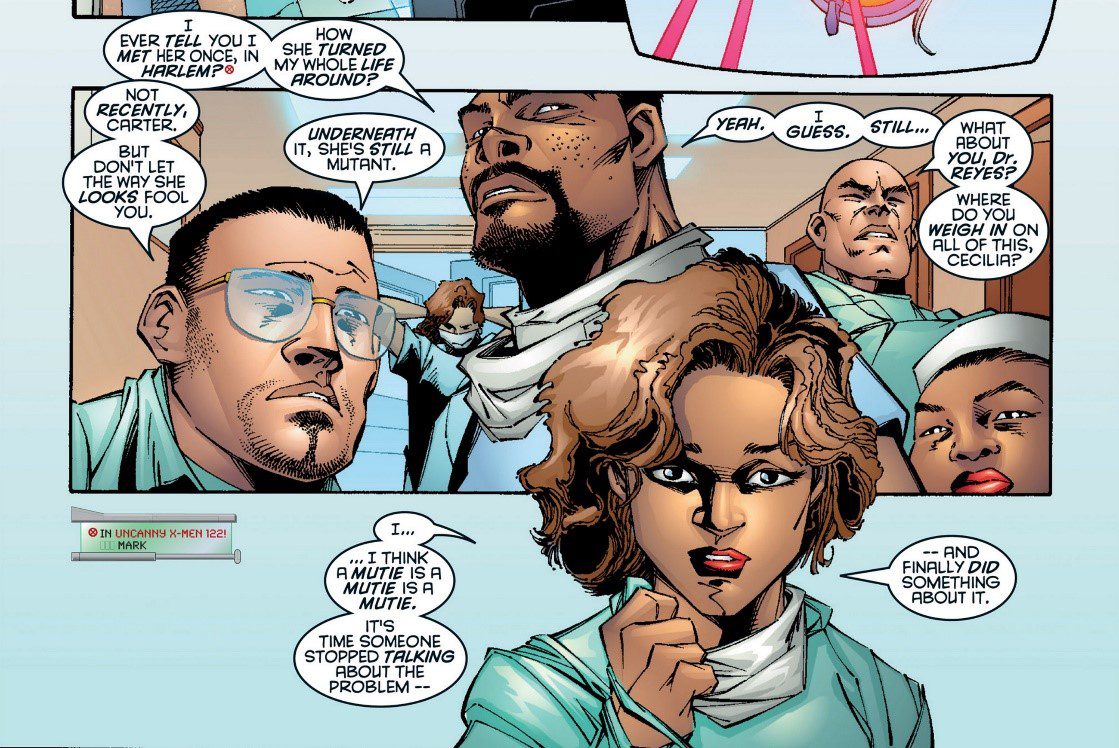

Reyes appeared briefly in issue 65. Her cameo occurred halfway into the book when the story transitioned to a hospital emergency room in the Bronx. This scene included a multi-ethnic group of doctors discussing a live television news report about a fight between Mutants and the military. The doctors were debating whether or not Mutants could be trusted. Reyes walked into the conversation and was asked for her opinion. In response, she made the following vague remark after loosening a surgical mask from her face: “I think a Mutie is a Mutie is a Mutie. It’s time someone stopped talking about the problem — and finally did something about it.” Afterwards, the story immediately transitioned away from the Bronx hospital and Reyes did not appear again until the next issue.

Although brief, Reyes’ first appearance and first statement were significant. Her comment about Mutants was inspired by Gertrude Stein’s famous quote “A rose is a rose is a rose.” Stein’s readers assume “she was suggesting, perhaps, what a rose is not.” A rose is not the actions that you perform on it. A rose is not the emotions it evokes in you. A rose is simply a rose. Similarly, applying this same train of thought to Reyes’ comment would lead us to assume that she is also implying that a Mutant is simply a Mutant; they are not the fearful emotions that non-Mutants project onto them.

Yet, Reyes had an ambivalent stance on Mutants. Her suggestion that it was time someone “finally did something about it” was vague. On the surface, it may appear that she supported the belief that all Mutants were menaces. However, when interpreted with the Gertrude Stein quote as its inspiration, the reader can assume that Reyes wanted someone to prove that Mutants could, indeed, be trusted.

Nevertheless, much like an African American who might choose to pass for white, Reyes chose to keep her Mutant identity a secret from her co-workers. Similarly, readers were unaware that Reyes was a Mutant but it was clear that she was a physician–she wore medical scrubs, a surgical mask rested off of her face, and the staff addressed her as “Dr. Cecilia Reyes.” Her mere existence contradicted the stereotype that black women cannot be doctors. A black woman is a black woman is a black woman.

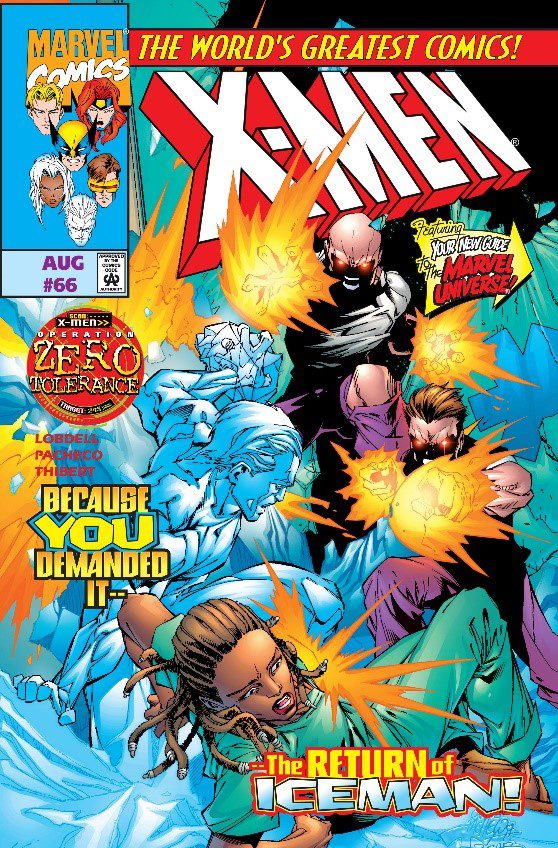

In the next book, issue 66, Reyes was the main protagonist. While she was included in the cover illustration, the cover text did not mention her. Readers may have not realized it was her because she had long locs of hair instead of the curly bob hairstyle from the previous issue. I asked artist Carlos Pacheco about this change was made and he replied,“comic characters arr [sic] human beings … and this is one of the things humans do.” Although Pacheco views this as a simple cosmetic change for Reyes, it can be a complicated decision for many black women because it touches on professional expectations, personal expression, and cultural sensitivity.

Black women who choose to wear natural hairstyles often face workplace discrimination. A 2016 study confirmed the existence of explicit and implicit bias against black women with natural hair in professional environments. Multiple cases have been brought forth against a long list of institutions, corporations, and schools with rules against Black hair. Furthermore, a federal court ruled that companies can fire people for having dreadlocks.

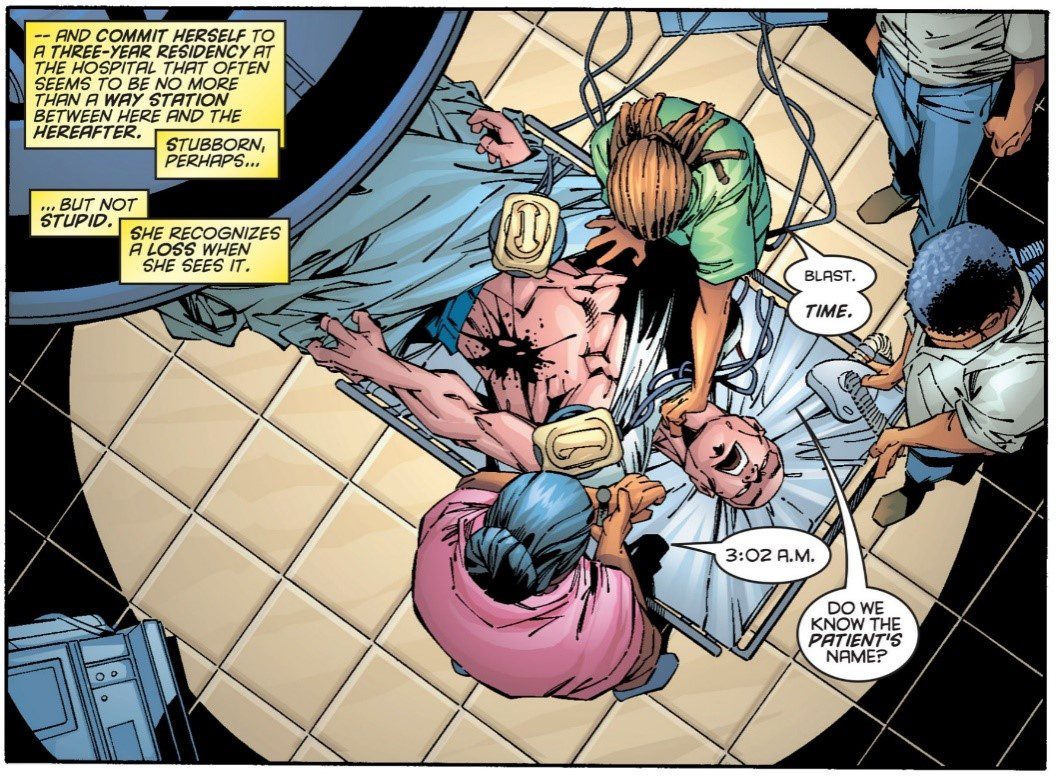

In issue 66, however, Reyes did not experience racial discrimination. To the contrary, she was portrayed as a confident doctor who was in command of her operating room. This could be a positive glimpse at an ideal situation in which black women’s hairstyles are not an invitation to question their abilities. Conversely, it could be seen as a lost opportunity to examine their common struggles with racism and sexism in the workplace. Yet, Reyes did encounter discrimination because of her mutant abilities. A mutant-hunting robot, a Sentinel, appeared at the hospital and attacked her. At that moment, we learn that Reyes has the ability to create force fields and fire projectiles at her opponents.

After Reyes was saved from the mutant-hunting Sentinel by fellow mutant, Ice-Man, she explained why she became a surgeon:

I was six years old, holding my father in my arms as he bled to death on the sidewalk. There was nothing I could do. Then. But I promised myself – and him – that the day would come that I could do something. That same night, I fell asleep reading my brother’s science text-book. Maybe it was just a devastated child’s way of dealing with a tragedy she couldn’t understand…but from that day on, I knew I wanted to be a doctor.

Illness or the death of a loved one is a motivation that Reyes shared with other aspiring doctors, including other black women. Additionally, she came from a poor neighborhood and become a doctor in spite of the false stereotypes that assume only students from high socioeconomic status families can become doctors. Like Dr. Sanneta Myrie, the 2016 Ms. Jamaica World, Reyes chose to return home to practice medicine. This is consistent with numerous other black doctors who return home to treat “populations that are traditionally underserved in medicine.”

Unfortunately, Dr. Cecilia Reyes is the only active black super heroine physician from a major comic book universe. In 1985, Dr. Midnight was introduced as DC Comics’ sole example but her character was killed in 1993. Independent comic publisher WildStorm Productions introduced us to Micro-Maid in 1999 but all of WildStorm’s titles were cancelled when the company closed in 2010. Dr. Cecilia Reyes, then, is the only lasting example of a black super heroine physician and she has appeared in approximately 500 issues.

While Scott Lobdell–the writer who introduced Dr. Cecilia Reyes in the world of comics–does not examine sociocultural topics relating to the lives of black women physicians, he does reveal Reyes’ Afro-Puerto Rican background in later issues. This provides an opening for exploring critical topics relating to hair textures, skin complexion, socioeconomic status, and heritage amongst Afro-Latinx groups. Although it can be refreshing to depict black women with locs in comic books practicing medicine without discrimination, it can also be empowering to see them model how to overcome the adversity black women still face even after earning their credentials.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.