Black Women and the Peoples Temple in Jonestown

On November 18, 1978, over nine hundred members of the San Francisco-based Peoples Temple church (including over three hundred children) died in the Jonestown, Guyana jungle settlement named after the church’s white founder, the Reverend Jim Jones. In what has been deemed the largest murder-suicide in American history, members died from a lethal cocktail of cyanide and Flavor-Aid supplied by Jones and his loyalists, who claimed that the community was under threat of racist annihilation. The Jonestown massacre was the culmination of a night of terror and siege dubbed the “White Night,” precipitated by an investigation of the settlement by U.S. Congressman Leo Ryan. Ryan had been murdered earlier that day by Temple guards. Contrary to popular myth, some chose to take the poison while most were forced.

The massacre has become shorthand for the perils of religious idolatry and blind faith. It has spawned a virtual cottage industry of scholarly books, novels, films and plays. Last year, HBO announced that Jonestown survivor and journalist Tim Reiterman’s massive Jim Jones’ biography Raven would be the subject of a forthcoming film by Breaking Bad creator Vince Gilligan. Yet, despite the fact that nearly fifty percent of those who died were African American women (in a church that was itself at least 75% black), none of these literary and cinematic treatments have actually been by or about black women.

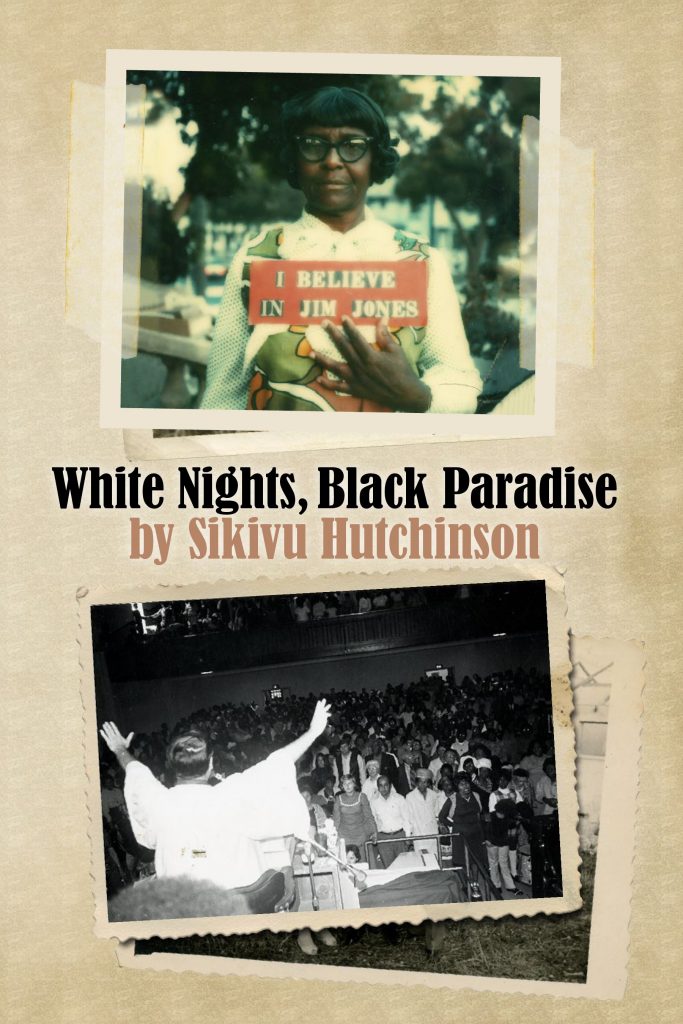

In 2009, Jonestown survivor Leslie Wagner Wilson published her memoir Slavery of Faith, becoming the first black female survivor to write a book on her life in Jonestown. The 2004 essay collection Peoples Temple and Black Religion, edited by Religious Studies scholars Anthony Pinn, Rebecca Moore (who lost several family members in Jonestown) and Mary Sawyer, is the only nonfiction book to provide context for the church’s political trajectory and connection to the black liberation struggle. However, my 2015 novel White Nights, Black Paradise is the first to focus specifically on the black women of Peoples Temple and the Jonestown massacre. The novel unpacks the deep social history, politics, interlocking relationships, diasporic hopes and dreams that compelled them to emigrate to Guyana.

My initial research was driven by what seemed to be one of the most basic and egregiously unanswered questions—where were the black feminist readings on and scholarship about Peoples Temple and Jonestown? As historian James Lance Taylor remarked to me recently, the erasure of black women is “a double victimization because the people who were victimized get hidden by Jim Jones’ ego (and) it made them into a bunch of freaks. It’s important to bring out that this was a significant event and it needs to be registered along the lines of major tragic events in black history.” Decrying the lurid tabloid frenzy around Jonestown, Taylor argued,

More than three decades of sensationalist media reportage has prevented a common knowledge among Americans…and most of all average black Americans, that Peoples Temple was as much a ‘black movement’ as the Harlem Renaissance, black labor struggles, the civil rights movement, the earliest stages of Black Power and modern day hip hop.

Founded by Jones in Indianapolis in the 1950s, Peoples Temple began as an activist church with an emphasis on multiracialism and civil rights. During the course of its nearly thirty year existence, the church (which relocated to Los Angeles and San Francisco in the 1970s) established social welfare programs, housing and health care for its predominantly African membership. The communal Jonestown, Guyana settlement was originally intended as a racial utopia free from the white supremacy, oppression and segregation of the U.S.

Many of the black female characters in White Nights, Black Paradise come to California at the tail end of the Great Migration. They are driven by the same “Promised Land” fever that spurred African Americans’ decades-long exodus from the South to the North. The church’s 1973 transition to the Fillmore community in San Francisco was the third leg of an internal migration that would culminate in Guyana. In a period in which most white mainline churches were segregated, Peoples Temple’s leadership was able to capitalize on blacks’ yearning for inclusion and cultural validation. In an era in which many Bay Area black churches were criticized for being bourgeois, Peoples Temple portrayed itself as an exemplar of black liberation struggle.

When she was introduced to Peoples Temple in the early seventies, former Los Angeles member Juanell Smart “had given up on religion, church and ministers.” For Smart and other black members, Peoples Temple was a bridge between the radical politics of the Black Power movement and the waning civil rights commitment of the Black Church. The Temple forged strategic relationships with the Nation of Islam, the Black Panthers and progressive black churches. In counterculture San Francisco, the church organized around affirmative action, affordable housing, police brutality, South African apartheid and the 1978 Briggs Initiative, designed to bar gays and lesbians from teaching in California schools.

Reflecting on her association with the church, Smart noted that, “I have always been a skeptic so it was hard for me to be a true believer for any length of time.” Smart’s skepticism led her to break from the Temple before Jonestown. Tragically, she lost her four children, her mother and uncle in the massacre. Now an atheist, she remarked in a 2014 interview, “I grew up believing that there was a sky god and he was going to take care of me. Then Jim came along and said that there wasn’t a god other than him. Jim aped what the black ministers said. Him calling himself God was a means to an end. What picture have people seen of Jesus Christ?”

Smart represented the rich religious diversity in the church. In the novel, Taryn and her sister Hy identify as agnostic and atheist. There are very few portrayals of black women skeptics in American literature. The most prominent ones that come to mind are in Nella Larsen’s 1928 novel Quicksand (the character Helga Crane) and Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 play Raisin in the Sun (the character Beneatha Younger).

Throughout its lifetime, Peoples Temple was described as Pentecostal, Christian, atheist and spiritual. These shifting designations were exploited by Jones according to context and political expedience. In 1973 he proclaimed, “The bible is the thing that brought us, it’s what they used to rip us out of the rich land of Africa and put us into chains as they’re still doing four hundred years later. So I question their bible and…their god who says ‘slaves obey your masters.’”

Jones loved to declare his “blackness” while playing the white savior. Indeed, the Temple’s pro-black politics masked a white power structure largely comprised of young white women (many of whom were sexually involved with Jones). They became his henchwomen and enforcers as the church grew more authoritarian. Hit by multiple allegations of abuse and fraud in the late seventies, the majority of the congregation emigrated to Guyana at Jones’ direction.

Yet, although there have been numerous portrayals of Peoples Temple’s shrewd politicking, the racial politics of gender in the church have been marginalized. In White Nights, Black Paradise, Peoples Temple is not only symbolic of progressive black social gospel traditions but of a racially divided women’s movement. It is no secret that white women’s leadership was resented by some of the black rank and file. In both the church and the Second Wave women’s movement, the veneer of interracial “sisterhood” was compromised by the reality of white female racism. In the novel, black women actively question and challenge this dynamic.

Nonetheless, for some black women in Peoples Temple, emigration to Guyana was a positive act of self-determination. In the novel, Taryn and Hy leave segregated Indiana for segregated California. Taryn finds that she is unable to advance at her new accounting job because she is a queer black woman. Hy becomes disgruntled by the city’s limited job market and its climate of racist police violence. Frustrated by these realities, their appetite for change is whetted by the prospect of Guyana. Ernestine Markham, a middle class schoolteacher leaves because she believes Guyana is a better alternative for her troubled son. Devera, a Black-Latina transwoman writer, yearns to be a pioneer in the Guyana settlement. Each woman is politicized by the times, her experiences in the church and the context of being black and female in what bell hooks has described as “white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy.” In the final analysis, the novel resists easy indictments, seeking to frame black women’s life-altering decisions in all their richness, complexity and ambiguity, in the shadow of a history long obscured by myth and nightmare.

Sikivu Hutchinson is the author of White Nights, Black Paradise and Moral Combat: Black Atheists, Gender Politics and the Values Wars. She recently completed a short film adaptation of the novel featuring a predominantly African American female cast. Follow her on Twitter @sikivuhutch.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thank you so much for your article. I was deeply disturbed when I first learned that the church started out with a civil rights/liberation model and that so many people who died were AA women. That fact is too often overlooked. Do you have suggestions for resources/readings also related to Jonestown?

Thanks for writing, and, yes, it is disturbing but the sociohistorical context of the era (conditions of disenfranchisement and dispossession in SF, decline/dismantling of grassroots black institutions, etc.) was an important factor in black women’s PT/JT trajectory. For further reading please check out Leslie’s book, Slavery of Faith, as well as Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America by Moore and Pinn. The Alternative Considerations of Jonestown website is also a treasure trove. There are testimonies from African American PT/JT members and survivors on the site.

I never knew these details of the Jonestown massacre it perplexes me that anyone let alone black women would have this devotion for to a white man or anyone for that matter. im lookin forward to watching.

There will be a screening and panel discussion with Black women survivors at San Francisco’s Museum of the African Diaspora on July 29th:

http://www.moadsf.org/?p=8807