Black Power, Name Choices, and Self-Determination

On March 6, 1964, Nation of Islam (NOI) founder Elijah Muhammad announced that he was renaming Cassius Marcellus Clay as Muhammad Ali. The Champ had previously bragged about his “slave name,” but began distancing himself from it when he joined the NOI. He claimed that changing his name was important because it released him from the psychological bondage of bearing the identity of his family’s slave masters. Shedding the name was a step toward freedom.

During the 1960s and 1970s, many Black Power activists joined Ali by developing strategies intended to overcome past and present racial oppression. They recognized that full liberation extended beyond legal and social gains. It included the ability to exercise self-definition and affirmation of their humanity on their own terms. Therefore, like Ali, many Black men and women made decisions about personal identifiers and surnames that reflected the complicated pursuit of self-determination.

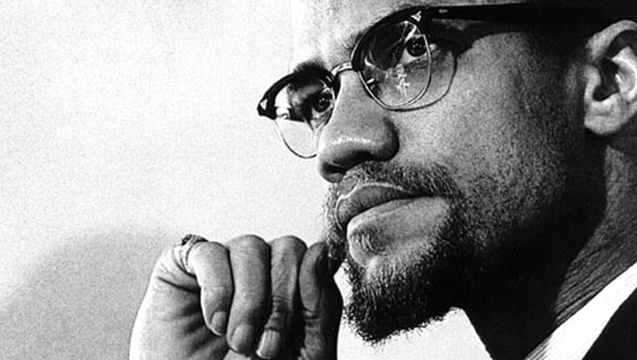

Although the conversation about naming has roots as deep as the African presence in the Americas, the politics of naming during the Black Power era found immediate inspiration in an iconic NOI minister. In 1952, Malcolm Little recognized the history of anti-Black violence embedded in his surname, so he dropped the name of his ancestors’ slave owner in exchange for an “X.” The letter represented his ignorance of his family’s “Original name.” His mentor Elijah Muhammad wrote in Message to the Blackman in America that so-called Negros must “be given names of your forefathers whose names are the most Holy and Righteous Names of Allah.” “[R]esolving your identity,” he explained, “is one of the first and most important truths to be established by God, Himself.”

When Malcolm X began internalizing Muhammad’s message, he was completing a prison sentence for a number of robbery convictions. His decision to drop his slave name, therefore, indicated that he was also giving up his former existence in exchange for the pursuit of knowledge of self and dedication to Allah’s will. Yet his experience with names spans much more time and space than his prison cell and his membership in the NOI. As a child growing up in Michigan, Malcolm remembered being called “nigger” and “Rastus” by his white teachers and classmates. As a hustler in Boston and Harlem, he earned such nicknames as “Detroit Red.” And while in Charlestown State Prison, other prisoners referred to him as “Satan” before he flirted with calling himself “Malachi Shabazz.” He was given the Yoruba name “Omowale” by some of his Nigerian friends and finally took on the name El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz before assassins murdered him. All of these names marked significant periods in Malcolm’s life.

As the patron saint of the Black Power movement, Malcolm’s name journey acted as a road map for many of those who carried on his work following his murder. They embraced the idea that the “lost tribe of Shabazz” needed to undo the shackles of slavery that, according to Malcolm, “cut these black people off from all knowledge of their own kind, and cut the off from any knowledge of their own language, religion, and past culture, until the black man in America was the earth’s only race of people who had absolutely no knowledge of his true identity.” For this reason, various Black nationalists chose to cast off their slave names in favor of African, African-inspired, and Arabic ones of their choosing. They saw self-definition through naming as an important step in a multifaceted Black revolution.

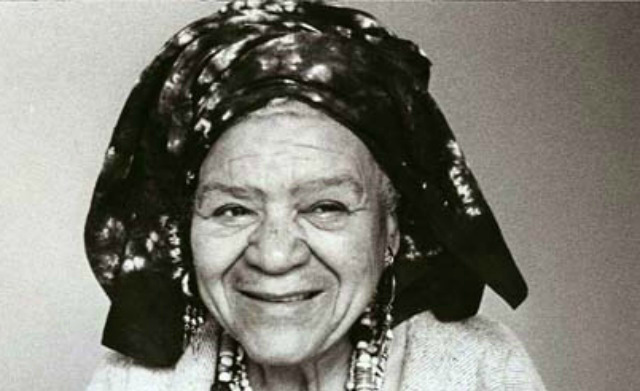

Black activists Queen Mother Audley Moore, Imari Obadele, and others who pursued territorial nationalism through the Republic of New Afrika (RNA) agreed that African Americans had to redefine themselves (or perhaps embrace their true “New Afrikan” identities). Living as a minority within another nation for so long led to a long and complex process of evolution which made it difficult for them to identify with other continental and diasporic African societies that had also changed and maintained a variety of distinctions among themselves. Instead, RNA theorists argued, African Americans should accept that they were “New Afrikans.” RNA applicants had the opportunity to choose new names to symbolize their New Afrikan identities and many of them did. In fact, early applications for prospective New Afrikan citizens included lines on which applicants would print their “Slave Name” and their “Assumed Name.”

Activists Njeri Jackson and Bokeba Trice were both given names with this understanding. Jackson received “Njeri” from children participating in a Kwanzaa celebration. This came after her husband’s unsuccessful attempt to free Imari Obadele from prison. Obadele gave Trice the name “Bokeba Wantu Enjuenti” during a naming ceremony after he completed the RNA’s nation building courses. Names such as Herman Ferguson and Marilyn Killingham, on the other hand, complicate the idea that one needed to take on a new name as an outward sign of their mental decolonization. Killingham, in particular, argued that she was honored to be named after her mother, an “African warrior.”

Members of Maulana Karenga‘s Us Organization also utilized names and naming to project images about Black self-determination. Naming was a part of the induction into the organization and signaled commitment to the revolution. Karenga often bestowed names upon members, officiating their membership and dedication to the political work of the struggle. According to historian Scot Brown, one woman named Joann Richardson was initially uncomfortable with the idea of taking on an African name. However, once Karenga christened her Kicheko, “one who brings smiles,” she accepted the name. Karenga had a knack for giving people names that either brought them praise or matched their personality. Kicheko, for example, accepted it because she agreed that she did indeed smile a lot. Another Us member felt that he was destined by God, so Karenga gave him the name Mtume, “messenger.”

Within the context of oppressed people struggling for liberation, it was important to consider the correlation between nomenclature and white supremacy. However, there was disagreement over whether reclaiming one’s heritage through the acquisition of African names was necessary. Some of the Oakland leadership of the Black Panther Party (BPP), for example, took a stance on name choices that differed from many New Afrikan citizens and Us members. BPP member David Hilliard argued that taking on African names did not have any revolutionary value. Accordingly, it was better to struggle for self-determination through “revolutionary nationalism” than to worry about clothing and names. Ultimately, he perceived the reclamation of African culture to be inconsequential if not counterrevolutionary.

BPP co-founder Bobby Seale and Raymond “Masai” Hewitt were two West Coast leaders who did not seem to agree with Hilliard. Although Seale did not take on an African name for himself, he named his son Malik Nkrumah Stagolee Seale. Following the long tradition of bestowing one’s offspring with “strong” names, Seale likened his son to the slain Black Power patron saint, Ghana’s first president, and the African American folk hero. Hewitt’s name connected him to anti-colonial resistance in Kenya and, specifically, to an ethnic group that many African Americans viewed as revolutionary. Further, BPP members in New York understood revolutionary nationalism as including mundane personal choices, such as taking on African and Arabic names and embracing African culture. With names such as Sundiata, as well as Assata, Lumumba, Afeni, and Zayd Shakur, they demonstrated that there was no one singular perspective on name choices.

As the names and the people behind them suggest, name choice was an important issue among Black Power revolutionaries. Although they all saw themselves as completing the work of Malcolm X, they did not have a uniform response to his stance on slave names. Regardless of where each group or individual stood on the matter, black activists’ participation in the discussion about names indicated that they were making careful decisions about how to identify themselves and how their self-determined humanity coincided with their revolutionary agendas. Therefore, if one took on a new name or held on to a birth name – and many activists did both – they were doing the intellectual and political work necessary to define exactly who they were and to prescribe a path to Black liberation.

Edward Onaci is an Assistant Professor of History at Ursinus College in Pennsylvania. He teaches courses that focus on modern U.S. history, women’s global political struggles, and African American history. Follow him on Twitter at @onaci7.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Well said Prof. My ex-wife and I gave our children non-Western names (Imani, Dharma, Vilaschandra) to empower their Spirits.

Beautiful written.Very proud, and proud of you.

Thank you for this nuanced interpretation. I know a CA Panther who named her child Freelimo. Passing along names of revolutionary movements were a key part of Black Power internationalism.