Black Power and the Gendered Imaginary

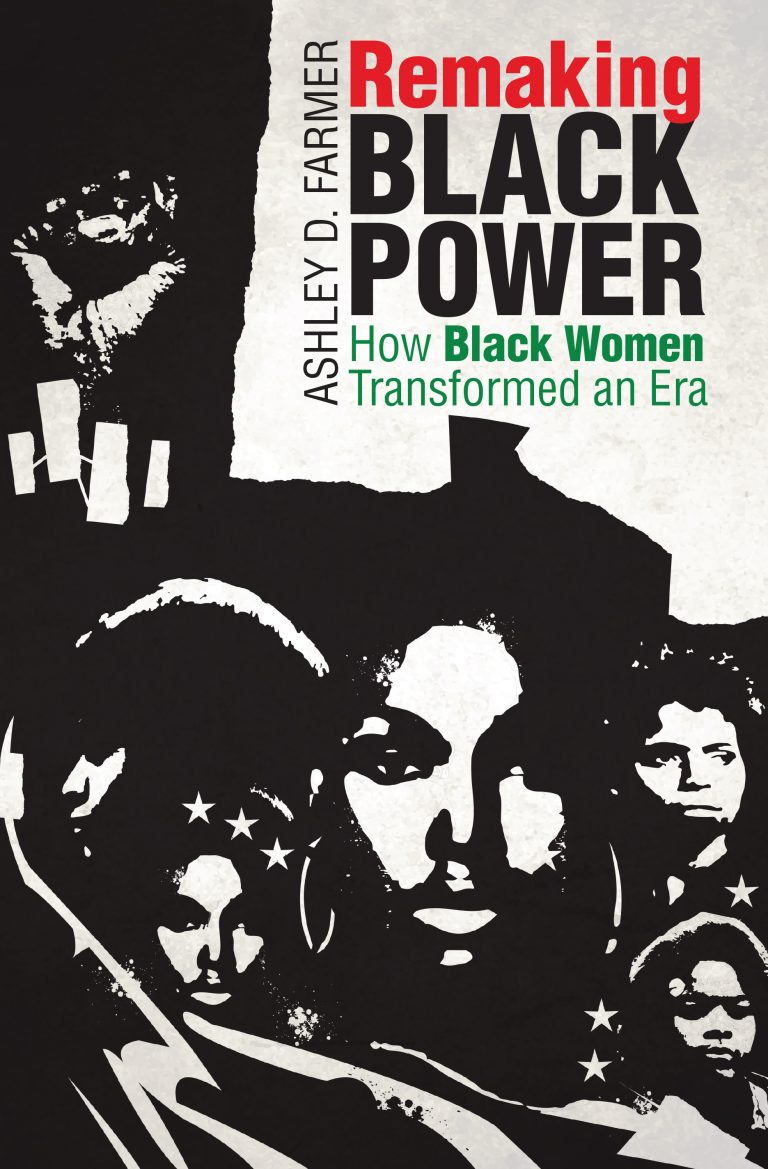

Ashley D. Farmer’s Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era is an essential new text in the recent historiography of Black Power. Remaking Black Power argues that Black women’s constructions, re/imaginings, and re/definitions of womanhood are crucial sites for the expression and building of Black Power. Farmer situates Black women subjects as integral components of Black Power, as she centers Black women as theoreticians, symbols, political actors via their ideas–their activism in concert with political imaginings, and their diverse visions of Black womanhood within the context of political and cultural organizing. She categorizes the contributions of Black women in the twentieth century as “The Militant Black Domestic,” “The Revolutionary Black Woman,” “The African Woman,” “The Pan-African Woman,” and the “Third World Woman.” The struggle and work produced by these Black women were inherently intersectional—they pushed against forced definitions of Blackness imposed by western/mainstream society and challenged sexist and limiting ideas of womanhood and gender produced by the larger patriarchal society.

Black women utilized their visual art, creative writing, speeches, and community work also to challenge the predominately men-centered popular beliefs of Black Power. The work created by these women pushed them into the center as opposed to them only operating on the periphery of Black Power, due in part to their re-imagining of leadership and action. Farmer argues that the redefinition and re-imaginings of self and identity conducted by these Black women are reflective of more extensive ideologies that Black resistance groups were following: the desire to redefine themselves outside the constructions and definitions imposed upon them by the white hegemonic power structure. In the first chapter, Farmer focuses on how the “Militant Negro Domestic” asserted her power and activism in the Black nationalist movement prior to Stokely Carmichael’s creation of the term “Black Power” in 1966. The next chapter centers Panther women in the heart of the most popular Black Power group, the Black Panther Party. Panther women directly proclaimed their agency to ensure that the Black Panther Party projected a less-patriarchal view of Black nationalism and international solidarity. The third chapter documents the evolution of the “African Woman” that challenged Karenga’s men-led Kawaida to incorporate a more feminist, anti-capitalist vision of Black activism that rejected gendered hierarchies. Chapter four examines the “Pan-African Woman” that forged solidarities with African nations resisting colonialism and those that acquired independence and sovereignty. Black women’s involvement in the planning of the 6th International Pan-African Conference in Tanzania highlighted the gender-inclusive modes of activism as a significant policy of the Black liberation struggle. The fifth chapter expands upon the previous chapter by closely examining the “Third World Black Woman” that aligned with all women of color and advocated for the erasure of gendered hierarchies in anti-colonial and anti-white hegemonic cultural-resistance struggles. Farmer is careful to distinguish between each model of Black womanhood, but also she lists how they overlapped, interacted, and left some aspects of patriarchal activism untouched.

A key concept in Farmer’s work is the “gendered imaginary,” which she defines as idealized, public projections of Black manhood and womanhood. This particular discourse traces how Black women’s ideological constructions of gender impacted Black Power ideals. Black women within Black Power who worked to redefine ideas and images of the Black woman created an important space that enabled Black women to engage in theoretical, ideological, and political activism all at once. The commitment these Black women had to re/self-definition helped to guide not only their own experiences but the overall ideological and tangible direction of the Black Power movement. This trajectory forced the Black Power movement into a more inclusive space dedicated to liberation for all instead of liberation for some. It put the theory of collectivism into action and attempted to disallow top-down masculinist versions of leadership.

Remaking Black Power offers several critical interventions to the literature on Black Power, Black political organizing, and feminism. The method that Farmer constructed for the book allows readers and future researchers to better see the imaginings of Black women during the Black Power era and how they envisioned a future society of freedom for themselves and their communities. Remaking Black Power pushes beyond the barrier of sexism and patriarchy of Black Power—which often hinders or overwhelms work produced about Black women in this era—to genuinely excavate how Black women were using the gendered imaginary as a radical space of reconfiguration, re/self-definition, and theorization of identity, power, and possibility. The introduction, however, should have more precisely articulated what scholarship the book challenges or engages.

Remaking Black Power foregrounds the study of Black women and Black Power written by Black women scholars, but it seems to neglect other scholars who equally contested the void of Black women as agents of Black Power in the historiography by producing work that centers and analyzes Black women. Scholarship by Erik McDuffie, Paul Alkebulan, Robin D. G. Kelley, and Jakobi Williams work serve as examples. Although Farmer mentions directly that the book is in concert with the work of Stephen Ward and Peniel Joseph, Joseph’s work exemplifies the “phallocentric readings of the era” that Remaking Black Power professes to question (12). While Farmer claims to challenge works that traditionally do not recognize women’s perspectives or intersections of politics and gender (15). She ultimately goes out of her way not to critique previous scholarship, and a historiography would have more clearly articulated exactly where Farmer intended the book to stand in the field of Black Power.

Farmer’s engagement with re/self-definition is but one of the many ways that Remaking Black Power is a product of Black feminist epistemology. Patricia Hill Collins notes that through re-articulation “Black feminist thought can simulate a new consciousness that utilizes Black women’s every day, taken-for-granted knowledge.” Farmer’s choice to elevate some lesser-known women, as well as her refrain of examining resistance in every-day practices such as with the “Militant Black Domestic,” combats limiting ideas of what leadership and political action look like in practice. She puts forth Black women as not only valuable political actors but also as sites of intellectual production. In a similar vein, Farmer’s project indirectly calls for the audience to acknowledge the genealogy of Kimberle Crenshaw’s “intersectionality.” While Farmer does not define the term or acknowledge Crenshaw until the end of the last chapter, she sets up the foundation for the concept throughout the book. For readers who are unfamiliar with the radical Black feminist landscape, it is difficult to recognize the idea without utilizing a map. Nevertheless, by following the nuanced ways in which Black women challenged masculinist tropes, readers can identify Black radical feminism through the practices of these activists.

For example, Farmer speaks at length of Claudia Jones’s “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of Negro Women,” an essay discussing how Black women occupy an intersection of multiple-oppressed identities. In fact, the entire first chapter of the book is primarily an ode to the early-building blocks of intersectionality. This act could not come at a better time, as intersectionality’s use has been challenged in recent years—scholars such as Jennifer Nash and others question whether it is meant to be used merely as an identity framework or something else entirely. Farmer reminds the readers that intersectionality evolves from a school of thought that targets those with intersecting oppressions, as well as multiple identities.

Chapter two, which focuses on the Black Panther Party (BPP), is simultaneously the most influential chapter of the book and the most problematic. The strengths are rooted in the Panther women whose intellectual and artistic productions the Panther newspaper published. Similar to Black Against Empire, Farmer primarily relies upon the Panthers’ newspaper to articulate the organization’s politics and history. Panther women such as Judy Hart (articles) and Tarika Lewis (art) demonstrate how the BPP newspaper was a space for revolutionary Black women. Lewis’s artwork set the tone for the Party by portraying both women and men as revolutionaries and protectors of the Black community. Hart’s articles led the publication away from patriarchal material. Combined, their work ushered in a Panther gendered imaginary that countered gendered tropes by highlighting Black women as revolutionary autonomous actors. In essence, Black women operated the BPP newspaper; it contained influential articles about and written by Black women, all of which contributed to the great strength of the book’s chapter.

By focusing primarily on material published in the Panther newspaper, however, voices, ideas, and contributions from outside Oakland (except New York) are rarely included in the book. Farmer’s examination is heavily bi-coastal and ignores those Panther women in between. Moreover, interviews of Panther women or documentaries such as Comrade Sisters (2005) could have provided valuable nuggets to support the book’s arguments, diversified the Panther women examined, and expanded the book’s sample size of Panther women’s ideas and contributions. In fairness to Farmer, she self-identifies the possible shortcomings of the book’s research methods. The direct and primary focus of the book is the intellectual and artistic production of Black women, which biases the book to examine mostly well-known organizations. This focus also limits the number of Black women members of such well-known groups who also contributed to the redefinition of the Black Power era. This point advocates that there is more to consider, and scholars will use Farmer’s work as a model and springboard to complete such scholarship.

Remaking Black Power is a significant addition to the men-centric historiography on Black Power specifically and Black women’s history broadly. It is a study of social justice and human rights struggles centered on the intellectual contributions of Black women, which expands our understanding of Black Power. The book critically challenges the dominant Black Power paradigm of Black women as doers/advocates rather than thinkers/intellectuals and theoreticians. The book does not present its Black women subjects as merely unsung heroines but as unacknowledged trailblazers whose leadership helped to create, maintain, and evolve the ideological tenets of Black Power. Farmer’s text joins a growing list of recent scholarly works that solidifies Black women’s places in intellectual history, which for too long have remained severely neglected. “Gendered imaginary” may very well establish a formidable theoretical framework for studying Black Power and other eras.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.