Black Panther, Engineering, and Afrofuturism

*This post is part of our new blog series on The World of the Black Panther. This series, edited by Julian Chambliss and Walter Greason, examines the Black Panther and the narrative world linked to the character in comics, animation, and film.

Engineering as a discipline and a profession is at a critical juncture. As often the outcomes of the engineering design process, technological solutions are becoming more deeply entrenched in our lives and our daily activities. They are also being called upon in response to some of humanity’s greatest problems.

While technology holds promise, the complexity of these problems requires the engineer to grapple with both the technical considerations and sociocultural implications of their designs and practices. Unfortunately, today’s engineer is often ill-equipped through current education and training to adequately address these non-technical concerns. This narrowed perspective not only often leads to a more monolithic view of both user and context of use but cultivates exclusionary design decision-making; fostering biased future solutions that are devoid of responsiveness to the needs and considerations of diverse groups. While usually an unintended consequence, the implications can be profound.

Black Panther, in its Afrofuturistic imagining of a technologically advanced African nation – Wakanda, motivates and inspires conversations around diversity and inclusion in technological design. Traditionally viewed as an aesthetic, Afrofuturism lies at the intersections of Black cultures, imagination, liberation, and technology. Sanford Biggers, in responding to Afrofuturism’s relevancy outside of a strictly aesthetic context, situates Afrofuturism somewhat as an epistemology: “Afrofuturism is a way of re-contextualizing and assessing history and imagining the future of the peoples of the African Diaspora via science, science fiction, technology, sound, architecture, the visual and culinary arts and other more nimble and interpretive modes of research and understanding.”

In its connection with engineering design, Afrofuturism as leveraged in Black Panther represents a means by which diverse possibilities can be cultivated and realized, expanding the technological solution space both in novelty and inclusivity. And inclusion matters in technology design. Without appropriate processes, countermeasures, and advocacy, we risk constructing technologies that “mirror a narrow and privileged vision of society, with its old, familiar biases and stereotypes.”

This challenge vividly and unfortunately reminds me of an 1999 essay in The Atlantic entitled “Technology Versus African-Americans” by Anthony Walton where he states, “It is important that we understand and come to terms with this now; there are technological developments in the making that could permanently affect the destiny of black Americans, as Americans and as global citizens.” And, as evidenced by this past summer’s viral video of a “racist” soap dispenser to the recent rallying cry by Timnit Gebru, cofounder of Black in AI, that “we’re in a diversity crisis…I want the Black community to be very aware of the ways in which data can be negatively affecting them so that they can then be more motivated to get into the field of AI and do something about it.”, the future as imagined by Anthony Walton, seemingly, is coming to pass.

Afrofuturism offers a potential antidote to Walton’s thesis. Complementary to design approaches that use science fiction to speculate on technological design and the future, Afrofuturism as a design lens facilitates a more empathic design engagement that explicitly places the often disenfranchised Black voice central in the design narrative, with an intent of universal betterment through and by technology.

At its core, Afrofuturism offers a bridge of empathy by connecting pertinent cultural insights and considerations to the engineering design dilemma. With this understanding, a more culturally relevant engagement can occur and more inclusive engineering design thinking can be fostered. In the context of my current research exploring the design of wearable technologies such as the Fitbit (known as connected fitness devices), Afrofuturism proves transformative and motivates design decision-making for more inclusive designs. It is particularly demonstrative in the design of connected fitness devices to improve health outcomes among Black women, for whom considerable health disparities exist.

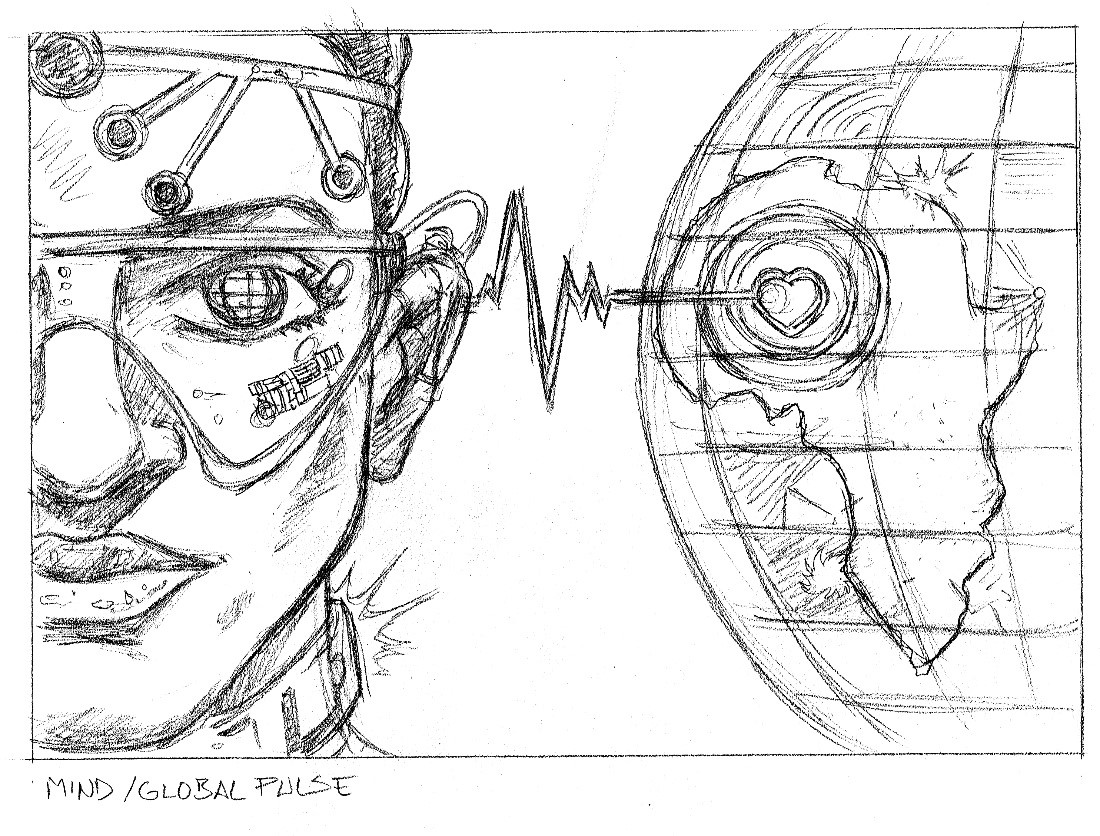

Grounded in the philosophies and efforts of GirlTrek, “an organization that inspires Black women to change their lives and communities by walking,” I collaborated with Pittsburgh artist Marcel L. Walker to reimagine, through an Afrofuturistic lens, a connected fitness design that is more responsive to the needs, motivators, and values of Black women than current available designs. Figure 1 offers one imagined connected fitness device concept that is emboldened by the spirit and imagery of Wakanda’s Special Forces the Dora Milaje.

From an interface and interaction design perspective, in particular, this concept conveys the importance of community and the value of connecting to a greater Black collective in contextualizing and motivating increased individual physical activity levels. Imagine the possibilities; particularly, in informing how the data and information offered by connected fitness devices be better synthesized, situated and visualized in engendering increased physical activity levels. While it is not the intent that the illustrated concept be implemented as imagined, it is the intent that this design artefact, as a probe within the engineering design process, provokes and triggers a more holistic conversation about both user and context of use in inspiring more inclusive connected fitness device designs.

Afrofuturism, thus, aids the engineer in identifying those relevant cultural factors that Blacks/African-Americans bring to the technologies that they use and fosters a design viewpoint that affords a more complete picture of all people. Afrofuturism affords greater reflection, intentionality, and voice to considerations of diversity and inclusion within the engineering design process. It is a design lens through which motivations and actions can be both catalyzed and implemented to increase inclusivity and, ultimately, equity within the culture and processes of engineering.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Someone who finally gets it!