Black October: An Introduction

2017 is not a year lacking in radical anniversaries. It marks fifty years since 1967, the year the Black Panther Party released their Ten-Point Program, which unequivocally declared: “We want an end to the robbery by the Capitalists of our Black Community.” It has been 60 years since Ghana, under the leadership of pan-Africanist and socialist Kwame Nkrumah, gained independence from the British Empire. Nkrumah would later write: “the total liberation and unification of Africa under an all-African socialist government must be the primary object of all black revolutionaries.” 2017 also marks forty years since the Combahee River Collective issued their 1977 manifesto of Black feminist liberation, which pronounced: “We are not convinced…that a socialist revolution that is not also a feminist and anti-racist revolution will guarantee our liberation.” What these declarations of Black radicalism share is a common referent, an unnamed antecedent that forced the world to take Marxist insurrection seriously: the Russian Revolution. In October of 1917, a mass movement led by workers seized power. Under the banner of the Bolshevik Party, tsarist Russia transformed into the world’s first socialist state, an event that would come to hold special meaning for the people of the African diaspora whose lives had come to be defined by the exploitation of their labor.

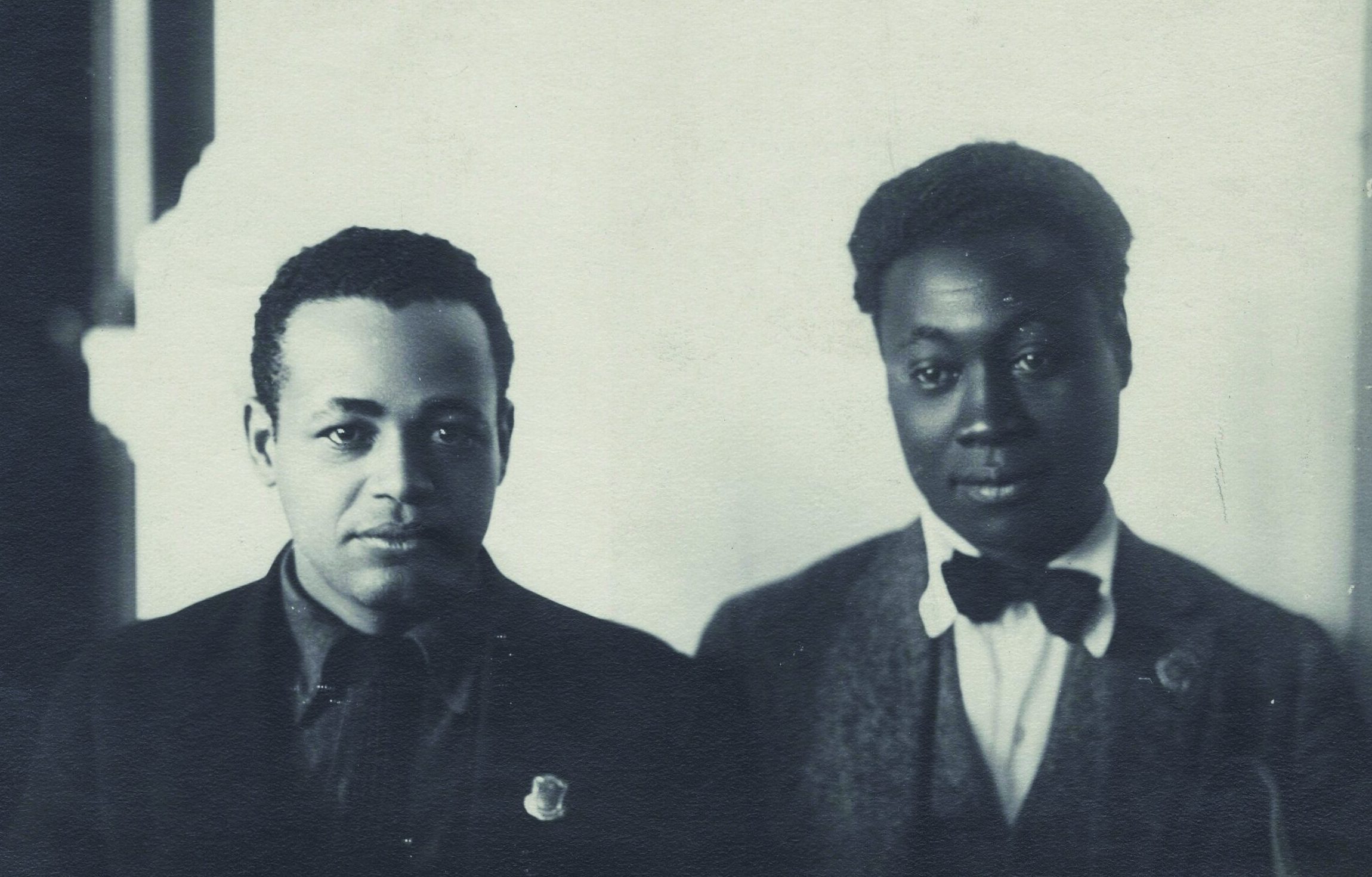

In this week-long forum of Black Perspectives, the contributing authors, who consist of scholars of Black history as well as specialists of the Soviet Union, help mark the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution by reflecting on what the existence of a worker’s state meant for Black people as well as what the African Diaspora meant to the Bolsheviks. The Russian Revolution inspired myriad cultural and political projects wherein Black activists and public intellectuals explored the potential for viable alternatives to capitalism. In kind, the Soviet Union sought to cultivate a global Black proletariat by nurturing these projects using hard and soft power. Multi-directional in scope, “Black October” will highlight these radical circulations. While addressing the relevancy of Black internationalism, this series also considers the Soviet Union’s use of Black struggle as a means of defining itself, both at home and on the world stage.

The Russian Revolution unfolded amid World War I, a pivotal event that did much to internationalize the Black political imaginary, particularly in the United States. Returning from war, many Black Americans reported seeing their own experiences with Jim Crow refracted in the anti-colonial struggles of people of African descent worldwide. As the West Indies born socialist Hubert Harrison wrote in 1921 for The Negro World, through the war, Black people “learned that Jim-crow street cars exist in Nigeria, India and Egypt, and that lynching, disfranchisement and segregation are current practices in the French Congo and in South and East Africa.” Thus, by the time of the Russian Revolution, Black radicals had already begun looking outward, internationally, for political inspiration. Indeed, many Black American communists joined the Party after participating in the African Blood Brotherhood and Garveyism–pan-African internationalist movements. The Russian Revolution and eventually the Communist International merely provided Black radicals a new platform upon which these transnational networks of solidarity could build.

As Black communists grew in number and the Communist International gained in force, so too did anti-communism. Black radical thinking on emancipation circulated through Marxist transnational circuits and faced fierce political opposition. For example, at the height of the Red Scare, segregationists accused the US Communist Party (CPUSA)–which had been active in anti-lynching campaigns and the fight to desegregate the country’s blood supply– of supporting “race mixing.” Likewise, Blacks fighting for racial equality were often labeled “communists.” Redbaiting smears were often coupled with accusations of Russian collusion. For instance, the socialist newspaper The Messenger (run by A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen) was described by J. Edgar of Hoover as “the Russian organ of the Bolsheviki in the United States.”

In Africa, the Soviets saw solidarity with Black struggle against European imperialism as a way to both expose the moral bankruptcy of Western capitalists and to increase its sphere of influence in the postcolonial Black world. To that ends, the Soviet Union became a fierce supporter of African independence leaders like Patrice Lumumba, Amílcar Cabral, and Kwame Nkrumah. To mark its commitment to African independence, the Soviet Union established the Patrice Lumumba People’s Friendship University (RUDN) in 1961; the university offered free education to students from developing nations not only in Africa, but in Asia and Latin America as well.

Underlying these various anti-racist campaigns was a belief, held by many Russians, that as a nation, it had historically done well in terms of the “Negro Question.” It had been on the right side of history, so to speak. Russia’s first political dissident, Alexander Radishchev, was an outspoken and early critic of the African slave trade. In his 1790 travelogue, A Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow, he condemned slavery as a horrific corollary to Russian serfdom. Greater still, Russia’s most celebrated poet, Alexander Pushkin, was of mixed Russian and African ancestry. To this day, Pushkin’s African ancestry looms large in the Russian imaginary as a testament to the country’s colorblindness; in the recently discovered novel by Claude McKay, Amiable With Big Teeth: A Love Affair Between the Communists and the Poor Black Sheep of Harlem (1941), the communist character Maxim tries to convince a young Black woman that the Soviets don’t believe in race, citing the literary celebrity of Pushkin.

Despite this, there remained a lingering mistrust of the Soviet Union. The Bandung Conference (1955) and the Non-aligned Movement both raised questions about whether or not the Soviet Union could be fully trusted as an ally in the fight against colonialism given its repression of Central European dissidents. And some Black radicals, like Black Panthers Elaine Brown and Huey Newton, still saw the Soviets as fundamentally white. Brown and Newton instead looked to Chinese communism as a model for people of color liberation. As Betsy Esch and Robin D.G. Kelly put it in their seminal article “Black Like Mao,” Chinese communism “offered black radicals a ‘colored’ or ‘Third World Marxist’ model that enabled them to challenge a white and Western vision of class struggle.”

In fact, Black radicals had always been pushing the limitations of Marxism until it fully addressed their positionality within the global capitalist order. Claudia Jones, the Trinidad-born communist, campaigned throughout her life to center the “super-exploitation of black women” (marked by race, gender, and class oppression) within the Communist agenda. Many of Jones’s concerns would be echoed by Cedric Robinson. In his monumental study Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (1983), Robinson wrote that “Marx consigned race, gender, culture, and history to the dustbin.” But Jones, Robinson, and the Black radicals they inspired simply re-shaped Marxism to fit their needs (rather than consigning socialist critique of capitalist imperialism to any theoretical dustbin). Thus, Black Marxist thought was never a practice of adoption, but of adaptation and improvisation. As the Trinidadian Marxist CLR James wrote in his 1939 statement (drafted for his meeting with Leon Trotsky in Coyoacán, Mexico):

The Negro must be won for socialism. There is no other way out for him in America or elsewhere. But he must be won on the basis of his own experience and his own activity.

Indeed, despite the Russian Revolution’s primary intervention in global politics—the introduction of a class-based revolution, the matter of race and the uniqueness of the Black experience was always inescapable as the Soviet Union tried to forge alliances with radicals of the African diaspora. Could the Soviets ever fully appreciate race? Was Marxism sufficient to address it? Or did Black communists have to invent a new praxis, all their own? The contributors to the Black October forum grapple with these questions while asking their own. They plumb the various iterations of radical hope that the Russian Revolution inspired while simultaneously asking if those hopes were radical enough. As Hakim Adi, the forum’s first contributor invites us to consider— what happens when “another world is possible,” but that world is “not a utopia.”

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.