Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom

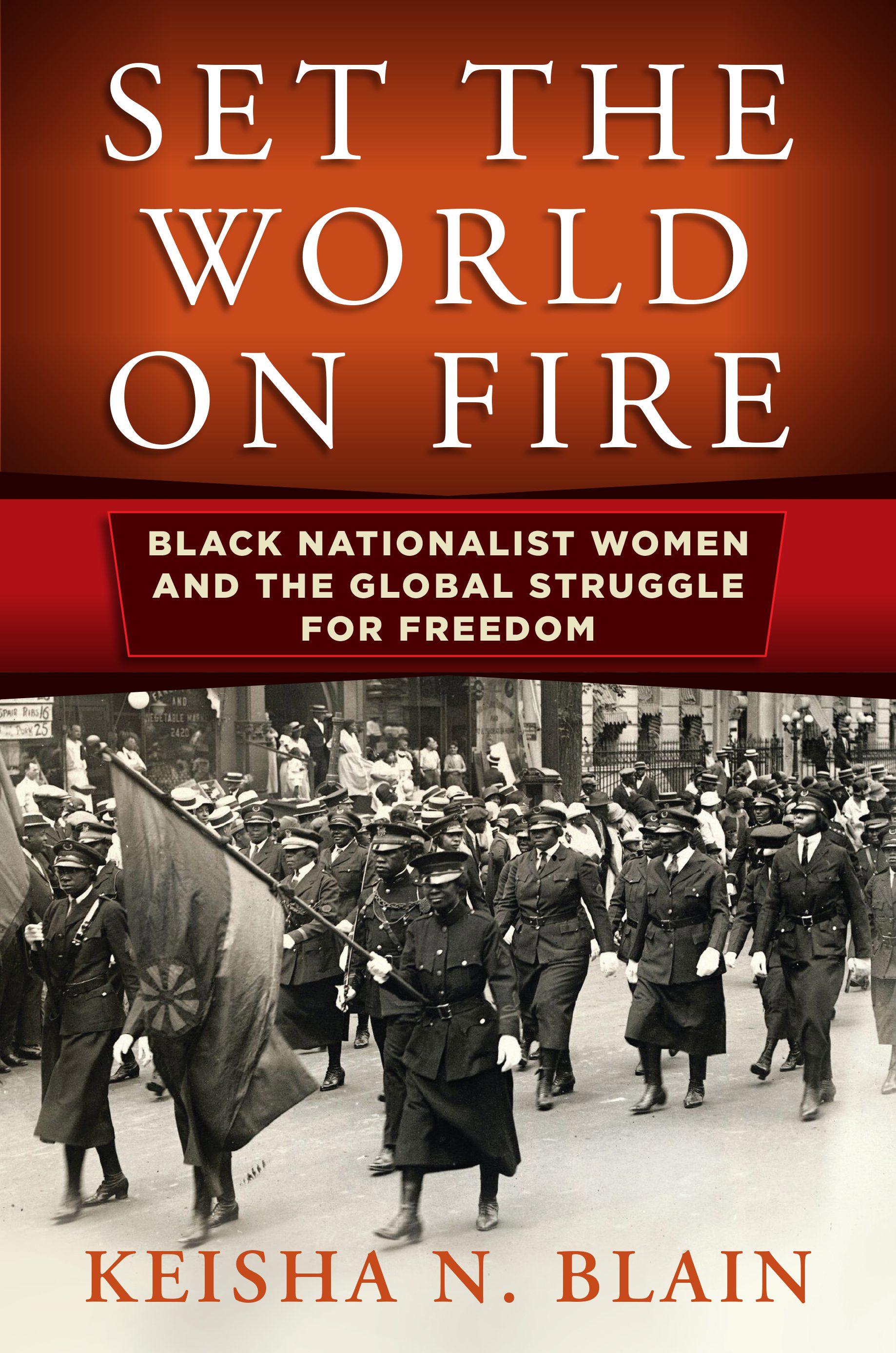

This is an excerpt from Keisha N. Blain’s Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018). In the book, Blain examines how black nationalist women engaged in national and global politics from the early twentieth century to the 1960s. In Chicago, Harlem, and the Mississippi Delta, from Britain to Jamaica, these women built alliances with people of color around the globe, agitating for the rights and liberation of black people in the United States and across the African diaspora. Drawing on a variety of previously untapped sources, including newspapers, government records, songs, and poetry, Set the World on Fire highlights the flexibility, adaptability, and experimentation of black women leaders who demanded equal recognition and participation in global civil society.

Against the backdrop of World War II, a vanguard of black nationalist women leaders in the United States, Europe, and the Caribbean were at the forefront of an international Pan-Africanist movement aimed at eradicating the global color line. Maintaining a commitment to anticolonialism and Pan-Africanism, these women, from all walks of life, employed a range of political strategies and tactics in their efforts to secure universal black liberation. Through various mediums including journalism, media, and overseas travel, Amy Bailey, Ethel M. Collins, Amy Ashwood Garvey, Una Marson, and many other black women activists and intellectuals fought to advance anticolonial and Pan-Africanist politics while articulating protofeminism. Reflecting the richness and complexity of their political thought and praxis, black nationalist women’s anticolonial visions often stood side by side with imperialist and civilizationist discourses. Likewise, their views on women’s rights and gender roles reflected the diversity of black feminist thought at the time, which was by no means monolithic or always progressive.

Significantly, these women helped to sustain black nationalist politics, endorsing racial pride, African heritage, black political and economic autonomy, and Pan-Africanism during the tumultuous years of World War. In the postwar era, black nationalist women in the United States and in other parts of the diaspora amplified their efforts to obtain human rights. In the absence of crucial diasporic newspapers like The African and the New Negro World, black nationalist women remained steadfast in their resolve to disrupt the global color line and found new avenues from which to articulate their views. Moreover, they continued to build transnational alliances, recognizing that their struggles for black rights on the local and national levels were deeply connected with struggles for freedom all across the globe. As many of these women grew older in age, some with failing health, they actively mentored a younger generation of black women who would be ready to carry on the work in their physical absence. The global visions of freedom black nationalist women promoted in their writings and speeches during the 1940s remained salient in the decades to follow—no doubt providing a source of inspiration for black activists and intellectuals during the 1950s and 1960s.

***

In a 1956 letter to a political ally, sixty-seven-year-old Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, the founder of the Peace Movement of Ethiopia (PME), insisted that the fight for universal black liberation was far from over. “It seem[s] that all our work is in vain, [b]ut we shall continue as long as we live,” she explained. Gordon’s comments captured black nationalist women’s unwavering determination to improve conditions for black men and women throughout the diaspora. During the postwar era, Gordon and other veteran black nationalist women leaders, including Amy Ashwood Garvey, Maymie De Mena, and Amy Jacques Garvey, continued to pursue a host of causes, including black emigration, anticolonialism, and black internationalism. Against the backdrop of the modern Civil Rights and Black Power movements in the United States, rapid decolonization in Africa, and a surge of liberation movements in Latin America, the Caribbean, and across the globe, these women continued to build transnational alliances and employed a range of strategies and tactics in their struggles for civil and human rights.

As veteran women activists grew older, they sought to maintain their political work, inspiring and mentoring a younger generation of black men and women who attempted to carry on the work in the decades to follow. In the United States, Gordon relaunched a grassroots emigration campaign during the postwar era, working alongside younger women activists in the PME. In London, Monrovia, and other locales, Ashwood, in her late fifties, continued the fight against racism and discrimination, forging transnational networks with a diverse group of black activists and intellectuals. From her base in Kingston, Jamaica, Jacques Garvey, also in her late fifties, advocated African liberation and black emigration to Liberia while also attempting to preserve and popularize the ideas of her late husband. Her colleague Maymie De Mena, who by this time was in her early seventies, supported these efforts, working with members of the Harmony Division of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in Kingston. Together, these women worked tirelessly to advance black nationalist and internationalist politics, unwilling to relent during a period of significant political change.

These women laid the groundwork for a new generation of black activists and intellectuals during the 1950s and 1960s. In many ways, the Civil Rights–Black Power era represented an extension of the political work that women like Ashwood, Jacques Garvey, De Mena, Gordon, and others had begun several decades prior. Ideological and organizational links tied new black nationalist and internationalist groups to older organizations established during the first half of the twentieth century such as the UNIA, the PME, and the Universal Ethiopian Students Association (UESA). Indeed, a new generation of black activists would draw upon the ideas and legacies of earlier black nationalist women leaders who preceded them.

The emphasis on grassroots political organizing, the commitment to Pan-African politics, and the ideals of black political self-determination, racial pride, African redemption from European colonization, and economic self-sufficiency underscore how a diverse group of black activists and intellectuals during the 1950s and 1960s—Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, Mary McLeod Bethune, Robert F. Williams, Mabel Williams, Mae Mallory, Malcolm X, and Stokely Carmichael, among them—drew on the ideological foundations and political strategies employed by earlier black nationalists and internationalists. Yet the organizational and ideological breaks between older and younger generations of activists were also evident. While younger black activists shared veteran black nationalist women’s anticolonial and anti-imperialist visions, many rejected the call for racial separatism, maintaining the belief that racial equality in the United States was achievable.

The historic Brown v. Board of Education ruling (1954) and the Montgomery bus boycott (1955–56) signaled to many black activists and intellectuals—including those closely aligned with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)—that change was not only possible but also imminent. Moreover, veteran black nationalist women’s particular focus on black emigration and their unwavering interest in Liberia marked a significant departure from the priorities of several black nationalist groups of the period. Rather than endorsing black emigration, black nationalist groups such as the Nation of Islam (NOI) and the Republic of New Afrika (RNA) advocated territorial separatism—the establishment of autonomous black communities within the United States. While black activists in these groups sought to advance economic self-sufficiency and political self-determination, they lacked the strong inclination to relocate to West Africa. Instead, they set out to empower black communities through various means, including religious expression, armed self-defense, and cultural nationalism.

During the Civil Rights–Black Power era, Gordon, Ashwood, Jacques Garvey, and De Mena continued to fight for the rights and dignity of black people in the diaspora—until they could physically fight no longer. In their absence, a diverse group of civil rights and Black Power activists and intellectuals emerged to lead the battle for universal black liberation, articulating visions of freedom that built upon yet also departed from earlier expressions of black nationalist and internationalist thought. Black nationalist ideas, made popular by earlier groups such as the UNIA and the PME, outlived and outgrew these organizations and their leaders—even despite the assault on black radical political activity during the early Cold War. Black nationalism not only survived but also thrived during the postwar era—taking on new shapes and expressions in a range of black political organizations in the United States and across the globe.

**Copyright © 2018 University of Pennsylvania Press. Reprinted with permission.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.