Black Journalists and The Great Migration

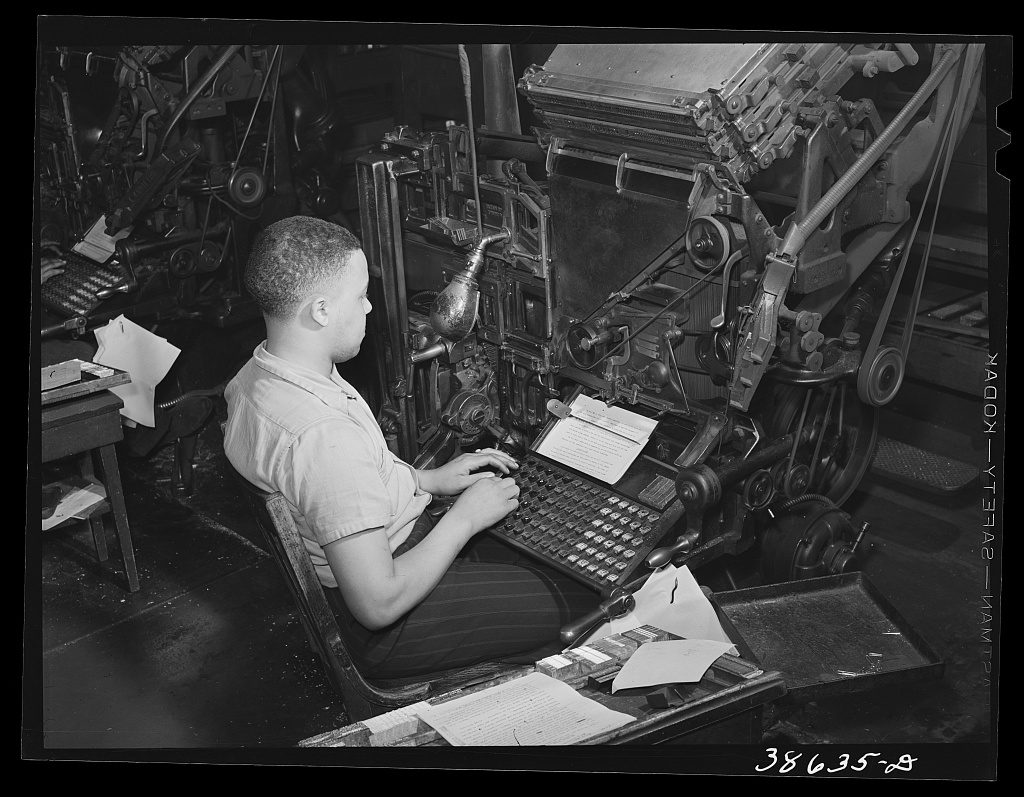

Coined in 1897, the phrase “all the news that’s fit to print” is a motto of the newspaper industry designed to reflect its impartiality in reporting the news. However, 1897 also constitutes part of the Jim Crow era during which the Southern white newspaper industry tended to ignore news related to or involving Black people. Into that segregated vacuum grew syndicates like the Scott News Syndicate (SNS), the subject of Thomas Aiello’s book, Practical Radicalism and the Great Migration: The Cultural Geography of the Scott News Syndicate (University of Georgia Press, 2023). As quoted in the book, sociologist Frederick Detweiler stated, “…the Negro has no other paper that will print him…many are the comings and goings of colored people that are never mentioned in the white man’s press. Why should they not have the normal satisfactions of publicity?” One of SNS’ functions was to provide Black newspapers throughout the South with national and local news articles that local papers often did not have the resources to cover themselves.

In chapters named after each of the Southern states, Aiello makes a solid case for newspapers under the SNS banner functioning as a continuation of the Black community grapevine; supplying that community with news, information, and editorials not found in the dominant media. It was that perspective which shifted me away from the occasional doldrums that I found myself experiencing in response to the book’s central theme of practical radicalism. I understand that what Aiello refers to as practical radicalism was (and continues to be) one of the many Black survival strategies necessary in a hostile environment. However, as someone who came to adulthood in a post-Black Power, post-colonial world, however, I wondered what purpose Aiello’s choice of practical radicalism as the theme of his book served. It was during such points that stories like the one found in the chapter on the two Carolinas stood out as a relatively more radical response to the oppression not even journalists were immune to under Jim Crow.

Despite being given practically radical advice by C.S. Scott, the owner of SNS, in 1950 while covering a case where a Black man was accused of raping a prominent white Greenwood woman, John Henry McCray, editor of South Carolina’s influential newspaper from 1941-1954, The Lighthouse and Informer, reported, without naming the woman, that the Black man said the sex was consensual. For this, McCray was indicted for libel, fined, and imprisoned. The next year, a judge ruled he had violated his probation and ordered him to serve a 60-day sentence on a chain gang. After McCray completed his sentence, he returned to his role as journalist, stating “I’d do it again” and “I accept it as nothing more than another step in our battle to obtain respect and our rights as Americans.” Even though McCray’s decision to not name the woman is considered by Aiello to be an example of practical radicalism, McCray’s experience shows that it was not always a successful method of avoiding Jim Crow-era abuses by authorities. Including these vignettes from the lives of people like John Henry McCray in the book, however, raises the tone of the book out of a Dragnet, “just the facts” style and more into the human dimensions of the survival mechanism that practical radicalism constitutes.

McCray was not the exception to the rule that most Southern Black newspapers and their publishers operated under the tenets of practical radicalism. However, he did move beyond the activism most Black publishers were involved in to one degree or another by starting a political party called the Progressive Democratic Party (PDP) in 1944. Although the PDP never won any elections in South Carolina, its existence did lead to more Black participation in South Carolina’s electoral politics.

There are other brief biographies spread throughout the book; stories that effectively highlight another theme of the book: that the SNS provided an invaluable service to the black community which spread far beyond a simple reading of the newspaper. Aggregated news articles of relatively defiant Black responses to Jim Crow in areas outside the South awakened possibilities in Black people who lived in the South. In other words, as a conduit for reporting on issues avoided by the white press, SNS was one of the contributing factors that led to the Great Migration.

As Black people migrated from the South, so did SNS’ coverage. In the last few chapters of Practical Radicalism, the cultural geography of SNS expanded to the areas where Black people landed: Michigan, Connecticut, West Virginia, Minnesota, etc. This required SNS to reach out to journalists who were not necessarily pro practical radicalism, due to their location in places where there was more breathing room.

While reading Practical Radicalism, Ida B. Wells crossed my mind. I was very interested to see if Practical Radicalism included any Black women journalists/publishers; especially since the majority of the Black male publishers quoted in the book generally referred to the community-wide interest in civil rights in the masculine. There are a few brief biographies included such as Kathryn Olive Hines, a music teacher, who published the Amarillo Herald and Alberta Gibson of Arizona who, in 1937, took over the publishing of the Phoenix Index. However, I got the sense that Black women publishers were constrained by what is now called respectability politics. For instance, one of the issues attributed to Black women was being referred to properly (miss/mrs instead of their first name). Of course, from the vantage point of the 21st century, such concerns can seem trivial, but considering Jim Crow eradicated social niceties, it was a point of contention…even though the Supreme Court would never weigh in on matters of politeness.

Overall, the information contained in Thomas Aiello’s Practical Radicalism is undoubtedly valuable and left me with a deep respect for the efforts of SNS as well as the other Black news syndicates referenced in the book. During a time when lynching was normalized, they profoundly changed the course of history by providing their reading audience with news ignored and/or trivialized in the white mainstream press.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.