Black History in the Comics

I have been reading comics my whole life, but it was only recently that I attended my first comics gathering, the Vancouver Comics Arts Festival (VANCAF), an annual event that focuses on the work of independent and small-press comics writers and artists. The highlight of the event for me was a Saturday afternoon panel titled “Re-Writing History: Research and Invention in Historical Comics,” where comics artists Lucy Bellwood, Tony Cliff, Rachel Kahn, Steve Couillard, and Kris Sayer discussed the processes, challenges and responsibilities involved in producing historically-oriented graphic narratives. While some of the panelists write comics that are set in relatively literal versions of the past and others use history as a launching-point for telling more fantastical stories, all of them discussed their approach to writing about the past in terms that echoed what one might hear in a university history department honors seminar. This was most notable when they discussed the need to read primary sources critically and the challenges involved in reclaiming the voices of the masses of people whose words never made it into the documentary record. Though their goals may be different from those of academic historians, these writers and artists take their obligations to history seriously, and, like academic historians, they are incredibly enthusiastic about the histories they write about and seem to love little more than a chance to “geek out” over a topic they are passionate about.

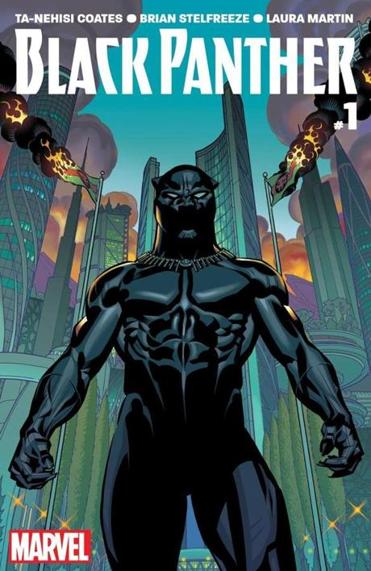

For many people who have not explored the remarkably diverse kinds of stories that comics can tell, the superhero genre is often thought of as representing the bulk of what the comics medium is about. Superhero titles were, if not absent, made up a very small minority of the work represented at VANCAF. That said, the one superhero title that many of the artists and attendees I spoke with were uniformly excited about was the Ta-Nehisi Coates-penned reboot of Marvel Comics’ Black Panther. As Dr. Walter Gleason wrote in his recent post about the “Wakanda Syllabus,” T’Challa/Black Panther and Wakanda, the fictional African country that he rules, have played important roles as “the fictional representation of those countless dreams denied; the unbroken manhood that Ossie Davis famously invoked after the assassination of Malcolm X [and] the dreams of black utopias like Ethiopia and South Africa that had grown as the Black Freedom Struggle grew over the twentieth century.” While Coates has said that his main goal in writing the series is to tell a good story, and that we “probably won’t see T’Challa at a Black Lives Matter rally,” he also notes that his experience “as someone raised within a black literary and cultural tradition” informs the stories he’ll be writing for Marvel.1 As critic Stereo Williams writes, “Coates’s status as one of the more high-profile commentators on race in America,” leads the reader to see Black Panther “as an allegory for the conflicting elements that contribute to so much of the black experience—a legacy of righteous rebellion born of oppression’s weight.”2

Given how my experience at VANCAF renewed my desire to see comics taken seriously as a medium for historical story-telling and the massive popularity of Coates’s work as a comics writer, I thought it would be fun to put together some brief reviews of a few recent comics titles that would be of interest to readers of this blog. This list is by no means complete (…it is largely limited to what I could find on my own bookshelves and those of my local library); if you have any suggestions of other titles that would be interesting to students of Black history, please leave them in the comments.

Part of the massive historical appeal of comics is, of course, the fact that they are generally easy to read. That said, more theoretically-inclined readers who are new to the medium may appreciate some basic comics theory to get a handle on how comics work. Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics and Reinventing Comics and Will Eisner’s Comics and Sequential Art and Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative are all good introductions to comics theory, but are by no means necessary to appreciate graphic narrative.

March (Volume I; Volume II ; Volume III is scheduled for release in August 2016) (Written by John Lewis; co written by Andrew Aydin; art by Nate Powell). In the 1950s, a comic book titled Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story was popular reading for African-American activists like John Lewis. Lewis has turned to the comics genre to share his memories of his activist history. The resulting trilogy is set on the day of Barack Obama’s 2009 inauguration. As Representative Lewis prepares to attend the inauguration, he meets an African-American woman who has brought her two young sons to the Capitol Building so they could see Lewis’s office and “see how far we’ve come.” Lewis tells them his life story and the story of his work with the civil rights movement while providing his insights on historical figures such as Ella Baker, Malcolm X, A. Philip Randolph and Martin Luther King. By moving back and forth between the past and the present, March draws our attention to the relevance of the freedom struggles of the 1950s and 1960s to more contemporary developments in American society.

The Harlem Hellfighters (Written by Max Brooks; art by Caanan White). This is the story of the legendary 369th Infantry Regiment, the African-American army unit that spent more time in combat during the First World War than any other American unit, winning multiple citations for bravery in the field. As it tells the story of the formation of the unit and the training and wartime experiences of the soldiers, the book focuses on the gap between the democratic values for which the war was ostensibly being fought and the profound (and official) racism faced by Black soldiers. The final panel, a rendering of the Harlem Hellfighter’s march up Fifth Avenue when they returned from France, balances a salute to the soldiers’ amazing accomplishments with the harsh reality that faced Black veterans and African-Americans more generally after the Great War: “The truth is that our fight, and the fight of all those who looked up to us as heroes, didn’t end with the “war to end all wars.”

Malcolm X: A Graphic Biography (Written by Andrew Heller; art by Randy DuBurke). Heller and DuBurke’s biography of Malcolm X doesn’t bring any new insight into the man or his times, but this fairly straightforward account would make a great introduction to the life and ideas of a key figure in black thought for younger readers. (There are at least two other graphic biographies of Malcolm X, Gary Jeffrey’s Malcolm X and the Fight for African-American Unity and Jessica Gunderson and Seitu Hayden’s X: A Biography of Malcolm X that I hope to review in a follow-up post). The more experimental style of Ho Che Anderson’s monumental King: A Comics Biography, uses a variety of artistic and conceptual approaches that not only provide a visually stunning account of Martin Luther King’s life, but capture the uncertainty, violence and chaos that defined much of American history in the 1960s and 1960s.

Another book that uses the expressive potential of comics to capture the tenor of the time it addresses is Coltrane, Paolo Parisi’s comics biography of jazz revolutionary John Coltrane. Divided into four acts corresponding with the four sections of Coltrane’s landmark recording A Love Supreme, the book moves back and forth in time in a way that, like Coltrane’s playing could, unsettles linearity in order to try to capture something transcendent or ineffable. This book sets the personal spiritual quest that shaped much of Coltrane’s music against the political landscape of the times, touching on the experience of growing up under Jim Crow, the church bombing which inspired Coltrane’s “Alabama,” and Coltrane’s relevance to the cultural politics of the Black Power movement.

Ed Piskor’s Hip Hop Family Tree (Volume I: 1970s – 1981; Volume II: 1981 – 1983; Volume III: 1983 – 1984) is an ongoing history of the development of hip-hop. Compared to Parisi’s Coltrane biography, the series does less to set the music into a larger political/historical context, but provides an incredibly detailed look at the personalities who played key roles in the emergence and evolution of the genre (though Piskor loses a few points for failing to talk about the Jamaican roots of hip-hop music and of its earliest pioneers in New York city).

It’s a great time to be a comics fan; changes in production have made it easier for small-scale and independent publishers to get the work of comics artists into readers’ hands, and the development of webcomics has meant that artists can get their work directly to readers at very low cost. It’s easier than ever to read the work of artists who are using the unique attributes of comics to tell meaningful stories with crucial political and social messages. That said, there are still (and probably always will be) those who still see comics as “kids’ stuff” and don’t take the medium seriously as literature, though I hope that this will be less the case as more scholars read comics and assign them to students alongside more conventional books. I’m looking forward to discovering more examples of graphic narrative being used to talk about history and will share more reviews in this space.

- First quote from J.A. Micheline, “Ta-Nehisi Coates on ‘Black Panther’ and Creating a Comic That Reflects the Black Experience,” Vice, 5 April 2016; second from Jonathan Gray, “A Conflicted Man: An Interview With Ta-Nehisi Coates About Black Panther,” New Republic, 4 April 2016. ↩

- Stereo Williams, “Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Black Panther: A Powerful Symbol for the Black Lives Matter Generation,” Daily Beast, 7 April 2016 ↩

Mat Johnson’s Incognegro: A Graphic Mystery comes to mind. It’s about a light-skinned black reporter who goes undercover in the South to cover lynchings. http://www.vertigocomics.com/graphic-novels/incognegro

Hi Chika —

Thanks for reading, and thanks for the recommendation. I’ll check it out!

Not sure if this is your field, but I would have loved to hear more about older black cartoonists and comics like Jackie Ormes and Ollie Harrington.

Hi Andrew — Thanks very much for reading, and while I will eagerly check out the names you mentioned, I’m not a comics scholar so much as I am a scholar who is interested in how contemporary comics artists use their medium to tell us stories about the past.