Black Historians, Race, and the Historical Profession

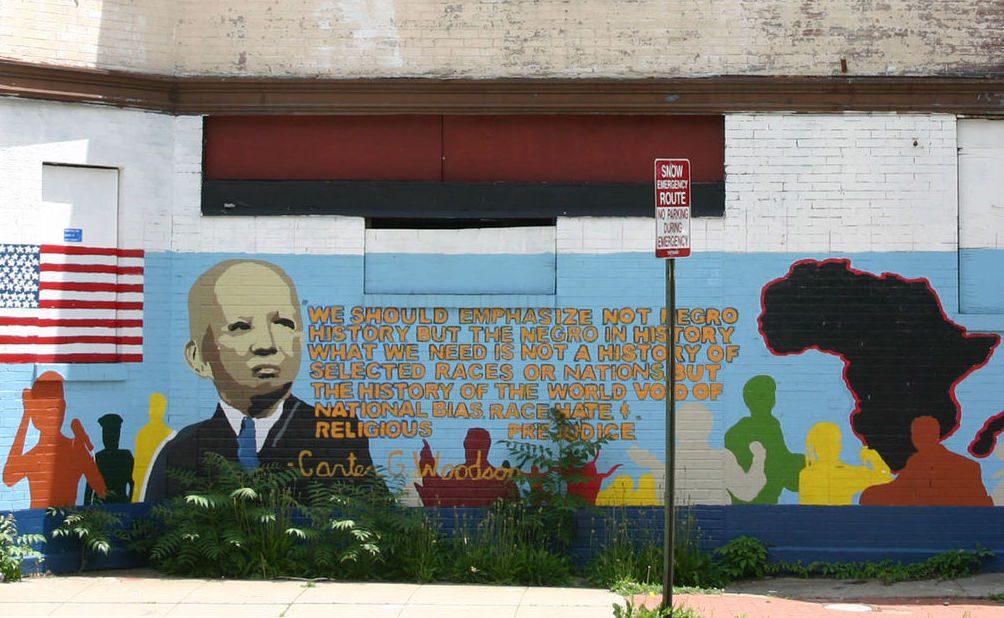

“History must restore what slavery took away, for it is the social damage of slavery that the present generations must repair and offset,” states Arthur A. Schomburg in his essay, “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” published in Survey Graphic in 1925. Closed out of the archive and prominent institutions of higher education in the post-Emancipation Era, the first Black historians were ordinary people and autodidacts such as William Wells Brown and George Washington Williams, identified by Stephen A. Hall in his important text A Faithful Account of the Race. These men and women were soon followed by a generation of highly educated Black professional historians, including Anna Julia Cooper, W.E.B. Du Bois, Carter G. Woodson, Rayford Logan, Dorothy Porter Wesley, Merze Tate, and Marion Thompson Wright. Black historians have long pushed the boundaries of historical studies and, in the process, shaped the discipline through innovative methods in their studies of racism in America and around the globe. The essay by American Historical Association president James Sweet—and his follow-up apology for the uproar it caused—has revived a conversation about the role of history in society.

Professional Black historians lived with and wrote about the ramifications of slavery, understanding that the past very much shaped their present conditions. It is not presentist to note that racial slavery has had an indelible and residual impact on the lives of African Americans down to contemporary times. This is a matter of fact that has been robustly documented in countless histories of slavery and the Black experience worldwide. Black scholars invented institutions such as the Association for African American Life and History (ASALH) and the Journal of Negro History (now the Journal of African American History) out of necessity due to American racism. And Black scholars continue to produce scholarship that has both redefined and revitalized the discipline as practitioners of what remains one of the most vibrant fields of inquiry in historical studies. African American history has been a significant growth area in the discipline for decades since the 1960s.

In their classic works, Black scholars identified the problem of American racism. They became innovators in historical studies by laying the foundations of African American history, Black Diaspora Studies, urban sociology, social history, American intellectual history, and Black feminist Studies. Cooper’s A Voice From the South: By a Black Woman of the South, published in 1892, reveals the roots of Black feminist thinking or an intersectional approach to knowledge that has come to dominate the academic discourse. Du Bois, with works such as The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America, 1638-1870, written as his dissertation at Harvard University, The Philadelphia Negro (1899), one of the first works of urban sociology, Souls of Black Folk (1905), and the groundbreaking Black Reconstruction in America (1936) challenged the racist dogma advanced by the Dunning School at Columbia University. While prominent white scholars such as William Dunning laid the ideological foundation of the Jim Crow system in their scholarship, Black scholars such as Cooper and Du Bois interrogated racism, sexism, and classism in American life from a historical perspective.

Marion Thompson Wright, who ironically worked with Merle Curti at Teacher’s College Columbia, produced a groundbreaking scholarship with her work The Education of Negroes in New Jersey (1941) that would lead to the dismantling of Jim Crow segregation in the South. Wright’s work became the basis of a significant case against school segregation in New Jersey (Hedgepeth-Williams vs. the Trenton, Board of Education), and she later conducted historical research for litigation on the part of the plaintiffs in Brown vs. Board of Education. Wright deployed techniques and quantitative methods later defined as “the new social history.” She was trained by Curti, a white scholar known for challenging racism within the discipline and understood to be a major architect of both social and intellectual history.

It has been Black scholars, quite frankly, in area studies of African Americans, women, and LGBTQ communities that have moved the discipline of history forward. V.P. Franklin, in his influential essay “Hidden in Plain View: African American Women, Radical Feminism, and the Rise of Women’s Studies Programs, 1967-1974,” about the rise of Women’s studies has demonstrated how it was Black women, by challenging racism and sexism in social science disciplines, who laid the foundations of both Black Studies and Women’s Studies in the American academy while also paving the way for sexuality studies. Leslie Alexander, in her article “The Challenge of Race: Rethinking the Position of Black Women in the Field of History” (2004), cogently reveals how Black women pushed the subfield of women’s history forward by understanding how race impacted the lives of women and by further interrogating the idea of universal womanhood. She notes that it was Black woman scholars who first moved beyond contributionist histories of women and shaped the discipline in noticeable ways. Countless scholars, including Martha Biondi, Ibram Kendi, Fabio Rojas, and Joy Ann Williamson-Lot, in book-length monographs, have illustrated the impact of Black Studies on American higher education. More recently, Stephen M. Bradley, in his essential book Upending the Ivory Tower: Civil Rights, Black Power and the Ivy League (2018), has demonstrated how the Black Power Movement, and the rise of Black Studies, have transformed higher education.

It is tone deaf for the leader of the nation’s most recognizable association for historical studies to be dismissive of the impact that racism has had and continues to have on African Americans’ lives while not recognizing the compendium of evidence that exists to the contrary. Further, the study of African American experiences and Black scholars have, in fact, revitalized the discipline in remarkable ways, as the record demonstrates. Regardless of how today’s debates about history continue to divide academia, practitioners of Black history continue to work hard to educate the public about the centrality of this story to the tapestry of American, and world, history.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

The institution of slavery, as well as the various forms of semi-slavery and

super-exploitation of African-Americans that followed Reconstruction has not only negatively impacted African-Americans today but the great mass of “white” people, a fact which, tragically, most European-Americans are totally unaware.

Thank you for this necessary and important piece. The suppression and erasure of the facts of the past have long been weaponized. An infamous example is Justice Taney’s 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford opinion. Taney cynically based his arguments on falsehoods about the American past, as I point out in my recent book.

At a moment when justices and the courts are, again, using their flawed understanding of the past to make decisions they are clearly stating are based on their idea of American history, “practitioners of Black history” are needed now more than ever.