Black Europe: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis

Co-authored by Kennetta Hammond Perry and Kira Thurman

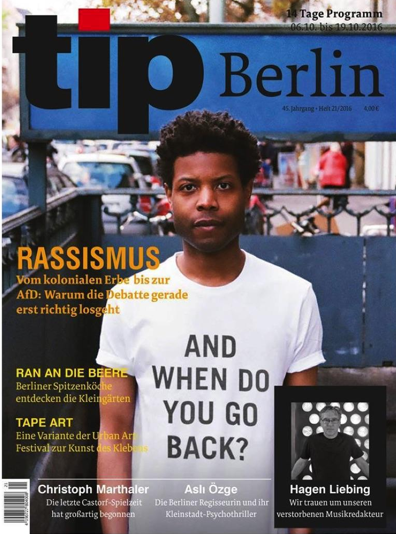

On the cover of the October 6 issue of Tip Magazine, a popular weekly magazine in Berlin, a Black man stares directly at the camera while wearing a white t-shirt with black letters in bold print. The t-shirt asks a simple question: “And when do you go back?” The man wearing the shirt is an artist named Isaiah Lopaz who has been living in Berlin for almost a decade. After encountering the same racist comments over the years, he decided to turn some of those questions and statements that White Germans had directed at him into t-shirt logos. Some of Lopaz’s logos point out the frustrating myth that we live in a post-racial society: “It’s 2014 no one cares if you’re black white or green.” Others assault the viewer with their everyday racism and false praise: “Even though you’re Black you’re really beautiful.”

But it is the question, “And when do you go back?” that is arguably the most damning and the most haunting. An assumption lurks behind that question that distances, isolates, and dislocates. By asking when the Black subject is going back, the White European implies that the Black figure was never part of Europe to begin with. It is a question that the Afro-German poet May Ayim addressed decades before Isaiah Lopaz decided to make t-shirts. In her 1985 poem, “Afro-German I,” Ayim depicts an exchange between herself and a White German in which the White German suggests, “If you work hard at your studies, you can help your people in Africa.” The notion that Black people’s place in Europe is transient and that their fates and futures lie somewhere else perpetuates the false paradox that it is impossible to be Black and European and defines Black people’s experiences on the European continent.

But it is the question, “And when do you go back?” that is arguably the most damning and the most haunting. An assumption lurks behind that question that distances, isolates, and dislocates. By asking when the Black subject is going back, the White European implies that the Black figure was never part of Europe to begin with. It is a question that the Afro-German poet May Ayim addressed decades before Isaiah Lopaz decided to make t-shirts. In her 1985 poem, “Afro-German I,” Ayim depicts an exchange between herself and a White German in which the White German suggests, “If you work hard at your studies, you can help your people in Africa.” The notion that Black people’s place in Europe is transient and that their fates and futures lie somewhere else perpetuates the false paradox that it is impossible to be Black and European and defines Black people’s experiences on the European continent.

For several decades, scholars of Black Europe such as Allison Blakely, Tyler Stovall, and Tina Campt have resisted the notion that it is impossible to be Black and European by exploring the histories of the African Diaspora in Europe. Collectively their work makes the case that the term “Black Europe” can be, to borrow from Joan Scott, a useful category of historical analysis. In documenting and analyzing the significance of diasporic communities in Europe, they have helped to create a vibrant field of historical inquiry that has been the subject of international academic conferences in Europe and North America and has resulted in the publication of important edited collections and curriculum-building efforts in England and The Netherlands.

But what have scholars meant by the term “Black Europe?” What type of intellectual currency does this particular category hold and what does it yield conceptually and methodologically for both the study of histories of Europe and simultaneously the Black Diaspora? As scholars continue to shed light on the complex histories of the African diaspora in Europe and beyond, it is important to consider some of the ways that thinking with Black Europe as a unit of analysis and as an epistemological approach can transform how we understand the shifting historical contours of Europe and ideas about Blackness. Here we offer some preliminary reflections on Black Europe and highlight some of the scholarship that is continuing to shape this dynamic field of inquiry.

But what have scholars meant by the term “Black Europe?” What type of intellectual currency does this particular category hold and what does it yield conceptually and methodologically for both the study of histories of Europe and simultaneously the Black Diaspora? As scholars continue to shed light on the complex histories of the African diaspora in Europe and beyond, it is important to consider some of the ways that thinking with Black Europe as a unit of analysis and as an epistemological approach can transform how we understand the shifting historical contours of Europe and ideas about Blackness. Here we offer some preliminary reflections on Black Europe and highlight some of the scholarship that is continuing to shape this dynamic field of inquiry.

First, the category Black Europe foregrounds the intellectual contributions of people of African descent and those racialized as Black in shaping European history, culture, and society. In their edited collection, Black Africans and Renaissance Europe, Thomas F. Earle and Kate J.P. Lowe bring together a wealth of scholarship that documents how the presence of people of African descent in places throughout southern Europe, including the 16th century court of Catherine of Austria in Lisbon, shaped ideas about wealth, the organization of domestic life and status. More recently, Felix Germain’s book, Decolonizing the Republic demonstrates that Black workers in France advanced their causes for social justice by demanding recognition as citizens of the state, and in so doing forced White French compatriots to change their definitions of Blackness and what it meant to be French in the post-WWII era.

Second, as a unit of analysis Black Europe complicates, unsettles, and disrupts racialized imaginaries of Blackness and Europeanness. It deconstructs the foundations of the Black/White binary that underwrites both of these categories and challenges ahistorical thinking that homogenizes their meaning in different temporal and spatial contexts. Lynn Ramey’s, Black Legacies speaks to this issue and examines the legacies of the Middle Ages in the construction of race and racism, highlighting the ways in which theories of Blackness were ever-changing and fluid. Moreover, her research underscores how work on the formation of Black Europe both materially and ideologically places Black history in conversation with European history. Threading the ties between these scholarly canons is both critical and necessary to enunciate the relationships between historical discourses of imperialism, racism, and (inter)nationalism and serves as a vantage point to understand the workings of what Robin D.G. Kelley, Tiffany Patterson, and others have described as Black globality.

To be sure, Europe’s relationship to the Black Atlantic was multi-directional, multi-purposeful, and often contradictory. In some cases, Europe functioned as a source of refuge for Black diasporic peoples escaping oppression from the Americas. But in other histories, as Andrew Zimmerman’s Alabama in Africa has taught us, African American institutions such as the Tuskegee Institute were complicit in oppressive projects of European empire-building, actively working with the German government to build a cotton plantation in Togo in the early 20th century. In doing so, Zimmerman shows that these relationships shaped ideas across the Atlantic about the role and function of Black labor and industrial education in the New South and in colonized Africa.

Thinking with Black Europe as an analytic also decentralizes and de-exceptionalizes the United States in the field of Black Studies more generally. In her work on geographies of race and nation in Liverpool, England Jacqueline Nassy Brown raises important questions about the power asymmetries that structure our understanding of diasporic communities historically and asks, “when does the unrelenting presence of Black America actually become oppressive, even as it inspires?” In posing this question Brown anticipates some of the arguments put forth in Michelle Wright’s book, Physics of Blackness, which rethink the category of Blackness in relation to space and time in such a way that frees us from seeing the Black Diaspora solely through a teleological lens rooted in the Middle Passage from Africa to the Americas. In doing so Wright urges historians to explore other epistemologies of Blackness that might not fit that paradigm and to better account for the differences between the lived experience of Blackness in various diasporic communities.

Thinking with Black Europe as an analytic also decentralizes and de-exceptionalizes the United States in the field of Black Studies more generally. In her work on geographies of race and nation in Liverpool, England Jacqueline Nassy Brown raises important questions about the power asymmetries that structure our understanding of diasporic communities historically and asks, “when does the unrelenting presence of Black America actually become oppressive, even as it inspires?” In posing this question Brown anticipates some of the arguments put forth in Michelle Wright’s book, Physics of Blackness, which rethink the category of Blackness in relation to space and time in such a way that frees us from seeing the Black Diaspora solely through a teleological lens rooted in the Middle Passage from Africa to the Americas. In doing so Wright urges historians to explore other epistemologies of Blackness that might not fit that paradigm and to better account for the differences between the lived experience of Blackness in various diasporic communities.

Finally, the term Black Europe provides scholars with a lens for thinking comparatively and transnationally about race politics and racial formation. Minkah Makalani’s In the Cause of Freedom and Marc Matera’s Black London offer views of interwar London that present Black internationalist politics as a product of encounters, states of exile, migrations, and transnational organizing between activists and intellectuals from the U.S., the Caribbean, Africa, the Indian sub-continent, and global leftist movements. Likewise, Anne-Marie Angelo’s article, “The Black Panthers in London, 1967-1972” has shown us some of the ways in which Black Power translated across the Atlantic in the fight against racism and imperialism. These works remind us that Europe has oftentimes served as a critical setting facilitating the types of intra-imperial, cross-regional forms of dialogue and intellectual production between diasporic peoples that have imagined radical alternative futures outside of the confines of both empire and the nation-state.

Our brief synthesis of these different scholarly texts highlights how scholars have resisted White global hegemonies by creating the field of Black European history. As a category of historical analysis Black Europe unifies the work of scholars studying different periods in distinct places—here, there, and in between—precisely because it provides a framework for us to ask questions, rethink relationships, and reimagine linkages and boundaries. Ultimately, scholarly work on Black Europe dismantles the false paradox that Black Europeans are placed into. Thus, by examining Black lives and experiences in Europe’s past, historians unsettle what it means to be European, and they unsettle what it means to be Black.

Kennetta Hammond Perry is associate professor of history at East Carolina University. She specializes in in Atlantic World history with a particular emphasis on transnational race politics, empire, migration and movements for citizenship among people of African descent in Europe, the Caribbean and the United States. She is the author of London Is The Place For Me:Black Britons, Citizenship and the Politics of Race. Follow her on Twitter @KennettaPerry.

Kira Thurman is an assistant professor of History and Germanic Languages and Literatures at the University of Michigan. Her research focuses on the relationship between music and national identity in European history, and Europe’s historical and contemporary relationship with the black diaspora. She is currently writing her first book, entitled Singing Like Germans: Black Musicians in the Land of Bach, Beethoven and Brahms.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.