Black Design in Chicago: An Exhibit and Symposium

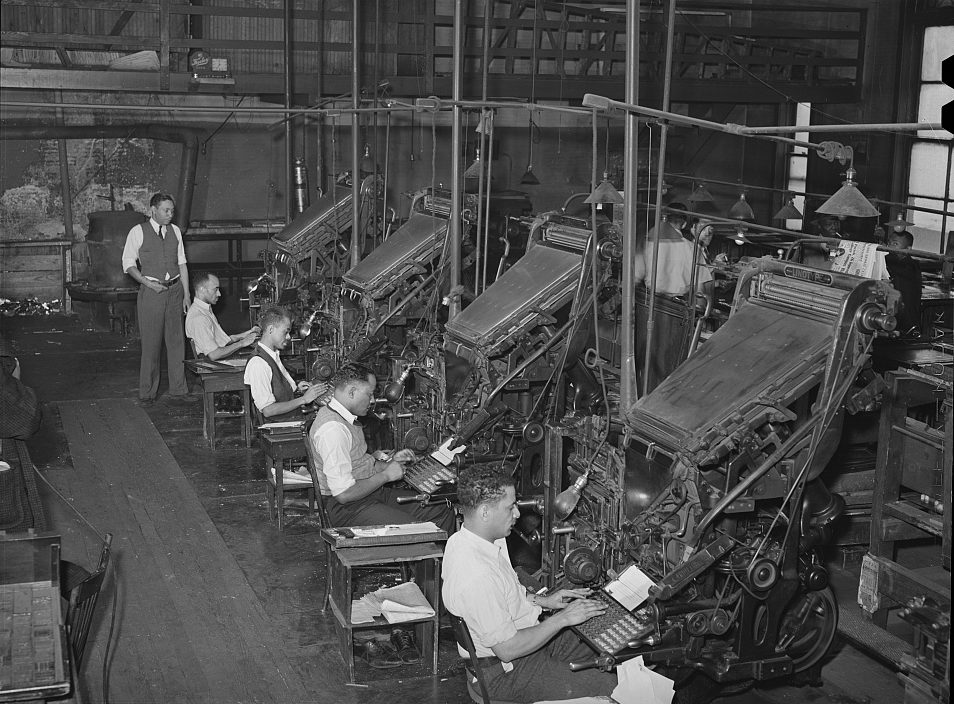

If Harlem was the capital of Black fine arts in the United States in the twentieth century, Chicago was the capital of African American consumer culture, a realization we owe to the scholarship of Davarian Baldwin and Adam Green. Building on the work of these and other historians, the Chicago Cultural Center opened an exhibit on November 2 documenting the aesthetic legacy of Chicago’s Black consumer culture called African American Designers in Chicago: Art, Commerce, and the Politics of Race. Part of a city-wide series of design events, an accompanying symposium, “The Designs of African American Life,” brought together scholars to share their work on a broad range of visual media developed by Black practitioners in commercial fields that included advertising, modeling, and magazine and book publishing.

While interest in Black design has certainly increased in the last decade, scholars have considerable work left to recuperate the history of design as a major arena for African American intellectual and creative production. Indeed, Black design, through its presence in popular media and the consumer marketplace, may well have reached a much broader audience than conventional high art forms.

Fittingly, Adam Green delivered the symposium’s keynote. As Green explained, a new era of scholarly interest in Black design can be traced to “African American Designers: The Chicago Experience Then and Now,” a conference organized by Victor Margolin and Charles Branham at the DuSable Museum of African American History in 2000. In addition to that conference and Green and Baldwin’s books that decade, more recent scholarly works shedding light on this topic include among others Tanisha Ford’s Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style and the Global Politics of Soul and Jason Chambers’s Madison Avenue and the Color Line: African Americans in the Advertising Industry.

Brenna Greer launched the symposium’s panels with a fascinating preview of her forthcoming book, Image Matters: Black Representation Politics, Capitalism, and Civil Rights Work in the Mid-Twentieth Century United States. Greer discussed the forgotten but critical role that pin-up photos played in the popularization of Johnson’s magazines. Jet may be best remembered for its brave decision to publish the deeply disturbing photographs of Emmett Till’s brutalized boy on August 15, 1955—but the cover of that famed issued featured Beverly Weathersby, a scantily clad, “pretty Los Angeles City College coed.” Greer’s analysis of sexuality on the pages of Johnson’s magazines offered a much needed re-assessment of the company’s complicated design choices.

My own presentation, “Black Bookstores and the Design of Black Power,” investigated a remarkable set of book covers produced by the Black nationalist Third World Press founded by Haki Madhubuti, Carolyn Rodgers, and Johari Amini in the late 1960s and 1970s. Some of the Press’s covers were created by Black Arts leaders such as Omar Lama, while others went uncredited, but together they represent an overlooked yet provocative corpus of illustrations and paintings that embodyed a Black Power aesthetic to market pamphlets and chapbooks.

Jason Chambers followed with a talk on African American commercial artists and advertisers in Chicago that focused on Emmett McBain, co-founder of Burrell-McBain Advertising. McBain pioneered a design style in the 1970s Chambers describes as “positive realism,” almost exactly at the post-civil rights era moment when white advertisers clamored to reach Black consumers. Yet at times McBain also employed a much more fantastic approach to advertising, as seen in one of his most memorable ads, a television commercial that portrayed the ghost of Frederick Douglass imploring a young man to use Afro-Sheen.

Kinohi Nishikawa extended the day’s discussion of book and magazine cover design with a provocative analysis of Herbert Temple, the artist best known for a dramatic black-and-white illustration for Ebony’s special August 1969 issue on the “Black Revolution.” Temple produced an astounding body of work for Johnson Publications in a career the spanned over fifty years, churning out illustrations for Ebony, Jet, Negro Digest/Black World, Ebony, Jr. magazines , and even an Ebony cookbook.

Elspeth Brown meanwhile led the audience on an exploration of Donyale Luna, the first ever Black model to grace the cover of a major fashion magazine when she appeared on the April 1966 issue of British Vogue. Luna navigated a challenging set of contradictory and racist demands imposed by a white-dominated fashion industry that expected Black models to be both glamorous and primitive. Additional talks for the symposium included Romi Crawford’s exploration of the Wall of Respect and Michelle Millar Fisher and Michelle Joan Wilkinson’s presentations on the impressive collections of Black design at their respective museums, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The accompanying exhibit, African American Designers in Chicago, is extraordinary. On display until March 3, 2019, the remarkable collection of original prints, paintings, and drawings shows how African American artists in Chicago worked at the forefront of a wide array of aesthetic impulses throughout the twentieth century—not only modernism, social realism, the New Negro and Black Arts movements, but also more popular forms like adult-oriented comics and concert posters. The range of creative works on display is truly impressive, and one can’t help but walk away convinced that Chicago’s concentration of Black artists, advertisers, commercial designers, and media outlets gave the city a singular distinction as the center of Black design in America.

Taken as a whole, this exhibit and conference represented an extraordinary set of scholarly and public events focused on the under-appreciated history of African American design and on Chicago as ground zero for that history. As Green argued in his keynote, Black design represents a “formulation and exercise of Black freedom, against the American tendency to deny African American independence as a rule.” If there was one city where Black design epitomized that expression of freedom, it was Chicago.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.