Between Diasporic Consciousness and Cultural Appropriation

Last month, writer Zipporah Gene, of Nigerian descent, set off a firestorm when she accused African Americans of “culturally appropriating” African fashions and style – specifically targeting those who attended this year’s Afropunk festival. To say these are “fighting words” is putting it mildly.

Last month, writer Zipporah Gene, of Nigerian descent, set off a firestorm when she accused African Americans of “culturally appropriating” African fashions and style – specifically targeting those who attended this year’s Afropunk festival. To say these are “fighting words” is putting it mildly.

While various African Americans sought to counter her arguments by stating how our experience of racial and economic oppression in the United States facilitated the historical erasures of our actual knowledge base of which West African cultures and tribes could be traced back to our ancestral lineage – hence why we claim the entire continent as a whole in attempts to display “Afrocentric” consciousness through visual displays of fashion and style – few actually engaged her critique of African Americans’ relative privilege within the global sphere of Black Atlantic and Black Diasporic politics and what that privilege means when we project a “futurism” by signifying on an African past.

Yes, as Tyree Boyd-Pates argues over at the Huffington Post, “When native African people restrict the cultural involvement of others based on their Diasporic location, they implicitly perpetuate the same colonialism that separated Africans from Africa.” However, what are the ways that our specific location within the U.S. – as oppressive as that location might be (from mass incarcerations to state violence to continued discrimination in housing and education and various “stereotype threats”) – places us at the center of the Diaspora or places us with particular power and privilege to influence the global and transnational spheres of culture or even to define racial discourse and the “black struggle”?

Anyone traveling to different points of the Diaspora – Jamaica, or Brazil, or Nigeria, or South Africa, or Toronto, or London – can pinpoint where African American culture has seeped into various black communities throughout the world (from celebrations of President Obama to our hip-hop and R&B artists playing in nightclubs, to “Black Lives Matter” adopted as a racial-justice rallying cry). We here in the U.S. can’t say the same about the rest of the Diaspora (unless we are already participating in those spaces here as immigrant communities or children of immigrants). Indeed, African Americans have enough opportunities to mix it up and learn from our local African and Caribbean counterparts, if we wish to expand beyond our own little enclaves, which means that our “dashikis” and “face paint” need not exist as mere “appropriation.” I venture to guess that many “African Americans” in the Brooklyn-based Afropunk event have direct connections back to the continent.

At the same time, what are the differences between “cultural retention” passed down from our enslaved ancestors – like Voudou or Candomble (a religious culture that even Nigerians have to travel to Brazil to learn more about – seeing that our New World ancestors preserved indigenous customs better than the continental Africans who were being colonized by Europeans, despite our slavery conditions) – and “cultural re-invention,” represented by nation-based modern concepts of the “Motherland” (afros, gele wraps, dashikis)? More importantly, how do we distinguish between these black cultural practices and the interracial practices represented by cultural appropriation?

Earlier this year, a fascinating art exhibit by Roger Peet sought to highlight the power and privilege of whiteness in adopting and simultaneously erasing non-white cultures. However, whites are not the only ones who engage in adopting cultures alien to their own. What remains to be seen is how we can move toward cultural exchange based in mutuality and respect rather than on power and privilege. This would mean recognizing those who participate in “cultural syncretism” (e.g. rapper M.I.A. clumsily attempted this with her “Broader than a Border” video, despite appropriation accusations) versus who engage in “cultural appropriations” (e.g. the Miley Cyruses, the Iggy Azaleas).

Beyond popular culture is the academic world, and my own research on South African historical figure Sara Baartman, the “Hottentot Venus,” was called into question by South African scholars who took me to task for collapsing her history into one of “black womanhood,” despite historical constructions of the racial differences between “Negroes” and “Hottentots.” Even before publishing Venus in the Dark, I would be remiss to not mention how my position as a U.S. scholar – despite being a black woman – paved the way for considerable access to Parisians museums, research centers, and even the South African embassy (arranged by a close contact with someone working in Paris’s U.S. embassy at the time).

The South African embassy contact I encountered rightly viewed me with suspicion during a volatile battle between France and South Africa when negotiations were taking place to return Baartman’s remains, which finally took place in 2002. Nonetheless, this South African embassy contact and I bonded over R&B music, which alleviated suspicions, “proved” our Diasporic blackness, and enabled us to engage in both political and cultural exchange.

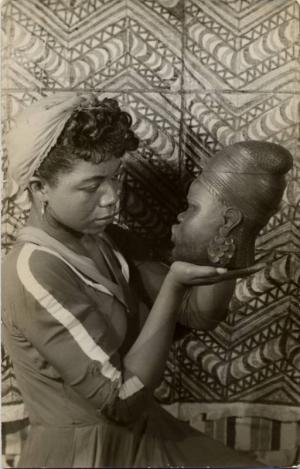

All of this is to say: Zipporah Gene needs more nuance in her own understandings of black cultural exchange, but her point about African American privilege within the Diaspora should not be dismissed. What does it mean when our most celebrated U.S. scholars and artists who championed the Diaspora – think Zora Neale Hurston, Katherine Dunham, and Lois Mailou Jones – accessed places like Haiti during U.S. occupation of the island and through prestigious academic grants? Then again, how do we position scholar-artists like Pearl Primus, with Caribbean roots and radical politics that made her a target by the U.S. government but her anthropological positioning allowed her to escape this country and deepen her dance scholarship on the African continent?

These pioneers, already stemming from longer traditions of Garveyism and Pan-Africanism, gave us important tools for decolonization and transcendence from “racial minority” status when thinking of global and transnational blackness. But if want to engage in more egalitarian forms of cultural exchange, we would have to seriously “decenter” African Americans in the Diaspora, as Brazilian scholar Patricia Pinho argues.

This does not mean that we should stop our attempts at “Afrocentric” fashions, as Gene suggests, but it might mean contextualizing local and global politics. Furthermore, such accusations work both ways. When filmmaker Steve McQueen was accused of minimizing the “African American” experience in 12 Years a Slave, since neither he nor the film’s stars were from the U.S., he flippantly remarked, “My boat went one way and theirs went another.”

Invoking what fellow Brit Paul Gilroy calls “The Black Atlantic,” McQueen gestures toward a Diasporic consciousness. But obviously our power and positions differ significantly depending on where our boats landed. We will need to remember this when attempting to engage each other with mutuality and respect.

Pictured: Pearl Primus

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

This sister of Nigerian can’t be serious! Nowhere are “white” cultural appropriations more apparent than in Nigeria! Where do you want to start? Whitening skin creams are some of the largest selling products in Nigeria. hair straighteners, toxic cosmetics, and plenty of European designer clothes and foods to make one “feel” more like the colonizers. While there are, indeed, some aspects of African culture that we ave acquired, they are not appropriations.

Where would American language or culture be without African descendants in America? What, in fact is American culture? What does it look like? Any perusal of the marketing strategies used in mass media today in the U.S. can clearly see the significant influence of the cultural appropriation of Black culture by whites who happily usurp our cultural ideas and profit from them without a single dime of it returning to the communities from which they “stool” those ideas. Joseph E. Holloway has written extensively on the subject of Africanisms in American English, properly referred to as the American Standard Dialect; as well as Africanisms in American culture. We must keep in mind that English is only spoken in Great Britain! prof. Holloway is only reiterating the work of Lorenzo Martin and some others who have done extensive work in that area of linguistics.

Next, Africans brought to the Americas, and in this case specifically the U.S.; were not a ragtag bunch of slaves, but Africans who were “enslaved” when they were brought here. They came from specific nations (not tribes, another colonial term) and most were brought from regions where they had specific skills. Those skills included planting agricultural products that whites could not do but needed for their survival. They came from many places and were known by those names for a long time. Each region had specific peoples in there area depending on the type of people needed and work to be done. The late Dr. Gwendolyn Midlo-Hall is just one example of the many scholars who have worked on that. You must keep in mind that “work” was something that most whites, especially the elites, did not do! Remember that the workers didn’t own and the owners didn’t work!

This brings me to Hip-Hop. The very word “Hip” in Hip-Hop is from Wolof meaning “to be aware, conscious”. WE we say someone is “hip” to something that means they are fully aware of that thing. Historically, from the time of the minstrel shows to to current performance activity, it was Black people whose cultural strategies that were appropriated by whites. The examples are legend, from Al Jolson to Miley Cyrus, David Clapton to the Beatles, Rolling Stones, etc. All of the previous white rock stars acknowledge their acquisition of cords and sound from Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Big Mama Thornton (Elvis Presley=You ain’t nothin but a hound dog). The influence of hip-hop culture, house music (Frankie Knuckles, Steve “silk” Hurley, etc. out of Chicago), Steeping and bopping out of Chicago, etc. All of these “cultural” forms are being utilized all over the world including and especially the African continent.

The value of the spiritual connections (Santeria in Santiago de Cuba, Candomble in Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, and Voodum in Haiti) are powerful examples of Africanisms practiced around the world and appropriated by Europeans. Obviously, the more historically johnny-come-lately spiritual forms of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism; are inappropriate for them and they are seeking something more closely associated with the “source” of spirituality.

In my judgement, this sister needs to go back and check herself because she is wrecking herself with those bogus assumptions. To conclude, I will let one of the premier White minds in curriculum studied, William Pinar,have the last word from his book; Pinar, W.T. (1994). Autobiography, politics and sexuality: Essays in curriculum theory 1972-1992. New York: Peter Lang.

William Pinar (1994) said it best when he stated:

The conservatives’ insistence upon the traditional school curriculum, an Eurocentric curriculum, can be understood as not only denial of self to African-Americans but to European-American students as well. White students fail to understand that the American self – in historical and cultural senses – is not exclusively a European-American self, it is inextricably African-American. (1994, p. 245)

Point taken: if we want to talk about appropriation, we really DO have to go back to the spurious notion that “America” was ever a “white country.” To do this, we only have to reality-test. Takes about 5 seconds.

However, the point seems to be that it is possible for African-Americans to engage in “appropriation” of “African” culture, by using visual expressions and cultural tools not just out of context, but in the absence of context.

Natives of America are clear about this: you are not “Indian” unless you can identify your people AND follow their ways. Wearing a dashiki while eschewing any cultural depth,–or worse, proclaiming oneself the sole arbiter of cultural expression, being dependent upon the ignorance of those in the diasporic community, is not something unknown in America. Whether done for afro-centric reasons or not, the opportunistic use of judiciously selected *parts* of “African” culture is problematic. Some better than none? Probably. But, at least, let’s talk about it and not shut each other down. Let’s air it and discuss it.

If you are a member of X Nation, do you recognize the hierarchy and your place in it? Do you speak the languages? How is culture shared if languages are not? Do you participate in the economic vitality of your in-group? Are you recognized as being a part of the in-group? What happens if X Nation is in a “hot” war with Y Nation,–do you conform? What if your DNA says you belong 85% to a Nation that has practices you really can’t go along with? Can you rely on the 15% based elsewhere to get a free pass?

The global diaspora has a lot of discussions to have, none of which are stupid or uneducated. These are, for example, important questions for anyone not born in, say, Tanzania, who wishes to go “home.”

But, then, maybe my American bias is showing.