On the Life and Times of Richard Pryor: An Interview with Scott Saul

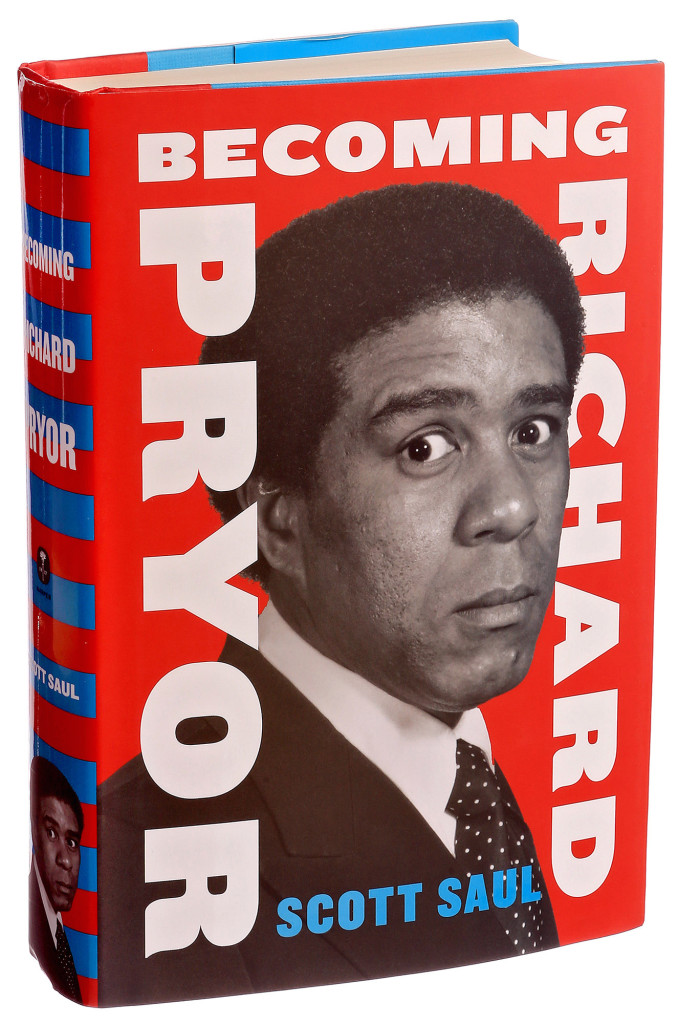

This month, I had the wonderful privilege of interviewing Professor Scott Saul on his recent book, Becoming Richard Pryor (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2014). Professor Saul teaches in the Department of English at UC-Berkeley, where he offers courses in 20th-century American literature and history. He is the author of Freedom Is, Freedom Ain’t: Jazz and the Making of the Sixties (Harvard University Press, 2004). His second book, Becoming Richard Pryor, was longlisted for the PEN Award for Biography. The digital companion to his Pryor biography, “Richard Pryor’s Peoria,” was named a top digital archive of 2014 by Slate. He hosts a books-and-arts podcast entitled “Chapter & Verse.” You can follow him on Twitter @scottsaul4.

***

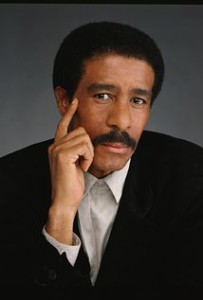

Guy Emerson Mount: Thank you for producing such a thoughtful and carefully researched work on arguably the most pivotal black comedian the world has ever known. Your biography is unique in a number of ways, not the least of which is that you offer something of a return to the inquiry into psychology that underwrites so many of the great biographies such as David Levering Lewis’s W.E.B. Du Bois and William McFeely’s Frederick Douglass. What are the risks and rewards of taking such an approach to someone who was not necessarily a politician or activist but instead an actor?

Scott Saul: I’m honored to be mentioned in such good company! And yes, my book is interested in the mind of Pryor, by which I mean that I try to recover his sensibility, intellect, and creative process. I do think of my book as ‘intellectual history’ in its 21st-century version — the version that allows for an expanded sense of who counts as an ‘intellectual’ and that understands that ‘the intellect’ has many faculties and dimensions, many of which were not represented in the earlier ‘history of ideas’ version of intellectual history.

From another angle, though my subject might not have been the sort of person whom professional historians tend to study (too much a “celebrity” or an “entertainer”), my methods were within fairly standard historical practice, especially when it comes to figures who leave no central archive. I rooted around in newspapers, journals, papers of activist groups, city council proceedings, Hollywood-related archives, FBI files, and the like; I located court documents (criminal proceedings, divorce proceedings) and, through the help of his widow, requested his school and military records; I interviewed anyone — his family, friends, lovers, creative collaborators, and so on — who might shed light on episodes of his life. (Many of the 70 or so people I interviewed passed away over the course of the seven years I was working on the book, so I felt fortunate to have reached them when I did.)

Once I had that research in hand, the question remained of how to reconstruct the mind of Pryor — what method to use in my account. I had no interest in putting him ‘on the couch’ or in providing a map of his unconscious; I think that the heavily Freudian school of psycho-biography has quite rightly fallen into disfavor among historians. Ray Monk, the biographer of Wittgenstein and Robert Oppenheimer (and a philosopher himself), has written a remarkable essay, one I recommend to any would-be biographers, in which he helpfully distinguishes between those biographies that advance an argument about their subject (Sartre on Flaubert, Edel on Henry James) and those that explore a point-of-view on him or her. Monk implicitly puts his own books in the latter category, which is where I would place my book too. I think it’s a more humble, supple approach that allows for certain details to “rhyme” with one another and establish patterns in the mind of the reader.

Once I had that research in hand, the question remained of how to reconstruct the mind of Pryor — what method to use in my account. I had no interest in putting him ‘on the couch’ or in providing a map of his unconscious; I think that the heavily Freudian school of psycho-biography has quite rightly fallen into disfavor among historians. Ray Monk, the biographer of Wittgenstein and Robert Oppenheimer (and a philosopher himself), has written a remarkable essay, one I recommend to any would-be biographers, in which he helpfully distinguishes between those biographies that advance an argument about their subject (Sartre on Flaubert, Edel on Henry James) and those that explore a point-of-view on him or her. Monk implicitly puts his own books in the latter category, which is where I would place my book too. I think it’s a more humble, supple approach that allows for certain details to “rhyme” with one another and establish patterns in the mind of the reader.

Because Pryor was an artist, as you point out, that meant that the models for my book were often in the genre of literary rather than political biography. I was much inspired by the great literary biographer Richard Holmes, who marvelously explores the rapport between art and life in his work on writers, like Coleridge, Gérard de Nerval, and Robert Louis Stevenson, who fashioned myths of their lives in their writing and then, in their lives, shadowboxed with those myths. I tried not to oversimplify the relationship between Pryor’s art and his life, but rather to see it as always dynamic. His art, even at its most autobiographical, was an interpretation of his life, not the ‘real thing.’

And the risks and rewards of this approach? Well, the risk is that it can be tempting to go further than your evidence allows: if you read enough biographies, you see this fudging with phrases like “so-and-so must have thought” or “so-and-so would no doubt have been surprised” (“must” and “no doubt,” ironically, revealing a sort of interpretative doubling-down when caution would be better). I tried to be extremely cautious — and my caution in turn spurred me to find more of a paper trail, or locate more people to interview, so that I could recapture the event in question in more detail. The reward is that, if the biographer does his or her job well, a reader gets a powerful double perspective on a life: the exterior perspective on the life (the life narrated, historically, from the “outside in”) and the interior perspective on the life (the life narrated, almost novelistically, from the “inside out”).

Mount: Your portrait of Pryor’s early life clearly complicates several competing notions of ‘the black family.’ What did family mean to Pryor and how might his experience with family prove instructive for historians hoping to write a more nuanced story about the complexities and diversity of black families?

Saul: Bonnie Greer, in her review of my book for The Independent, wrote that “The Pryors were people who, somehow, Richard managed to both expose for who they were. And ennoble.” I think Greer was getting at the moral complexity of Pryor’s act — a moral complexity that I tried to learn from, and that historians of black family life might too.

Kali Gross, in her recently published book, Hannah Mary Tabbs and the Disembodied Torso, has written about her need to write the stories of black women who “defied the customary narratives of suffering, resistance, and redemption”: “we have precious few examples,” she writes, “of black women who lived as people with depression and joy, with desire and love, as well as contempt and rage.” For me, one of Pryor’s great gifts is that, in his portraits of his family and himself, he was observant, not formulaic, and usually departed from the expectations of melodrama (where a victim, by virtue of his or her victimhood, is identified with good, and a perpetrator, by virtue of his or her harmful action, is identified with evil). Maybe it was because Pryor had been abused from all sides as a child and did not sense that the abuse had made him particularly virtuous; or maybe it was because, despite the harm he’d suffered at the hands of his grandmother Marie and father Buck, he still learned much from them and found his way to appreciate and love them; but in any case, he presented that tangle of abuse and love and did not simplify it for the edification of his audience. Strangely enough — Pryor himself thought it was strange — when you presented audiences with the incongruity in a sharp enough fashion, they tended to laugh.

On the question of complexity: other than Pryor himself, there’s no more complex figure in my book than his grandmother Marie, the entrepreneur of the family and the woman whose strength stands behind Richard’s. Trapped in an abusive marriage, she repeatedly brought in the law — white officers and white courts — to give her leverage against her husband. She didn’t belong to civil rights organizations, but she had a fierce sense of racial pride and used her physical strength to subdue those who insulted black children, even if that meant she’d be threatened with jail. She was part of the underground economy for much of her working life and was quite strict — to the point of often being brutal — in the way she ran the Pryor family brothels in the 1940s; yet she also ran a tavern, a beauty shop, and a small restaurant too, and these she operated with more conviviality. Within the family she was much feared (not just by Richard and his siblings, but even by his father Buck, himself a bruiser), but she was also the person who brought the family together — through her cooking, her practice of going to church, and the fairly loose parties that she threw for herself. So how would a historian categorize her? In her life she blurs many of the lines that historians tend to draw for the sake of schematization. But it’s in the blurring of those lines that — having been born poor and black — she found the way to achieve her strength. (She was an amazing woman: when she was interviewed on The Mike Douglas Show next to her grandson Richard, Sammy Davis Jr.—who was waiting to perform in the wings—was moved to say, “There ain’t no sense in nobody going on. The show belongs to her.”)

The Black Lives Matter movement has openly challenged the ‘politics of respectability’, and I imagine that historians will now take a page from the movement and write more about those who’ve lived outside respectability yet had a powerful impact on our political culture. The Pryors — from Marie through Richard —would furnish a great case study in this regard.

Mount: Some of the more gut-wrenching moments in the book turn on Pryor’s brutal redeployment of the violence he learned as a child upon his intimate female partners. Knowing that his upbringing caused him to strongly correlate physical violence with love, what was the way out for Pryor on this front where he might have escaped his misogynistic and patriarchal absorptions? What needed to happen or what contingencies might have caused him to exorcise these demons and break the cycle of abuse that his father, mother, and grandmother levied upon him?

Saul: First of all, it’s important to note that, in one regard, Pryor did break the cycle of abuse: from what I know, he was not physically brutal to his children, having processed what it felt like to be on the receiving end of that violence. Also, I’ve been told that, starting in the mid-to-late-’80s, he stopped raising his hand against the women in his life. Whether a particular partner had moved him to an insight, or he’d come to that insight on his own, or he’d been slowed down by the progress of his MS, I can’t say. Several women whom I interviewed, and who had been abused in the 1960s and early-1970s, spoke to me about how they felt so alone at the time — how there weren’t any women’s crisis centers or shelters for them to go to, and no larger cultural conversation about what had happened to them. So I think that the feminist movement deserves credit for working to change that (an ongoing struggle, obviously).

Here I’ll tell you a secret about my book — a secret I made no effort to hide, but no reviewer has pointed it out, so perhaps I should have been more explicit on this score. One of the things I aimed to do in Becoming Richard Pryor is give much fuller voice to the women in Pryor’s life — his grandmother Marie, his mother Gertrude (who, contrary to the myth, did not abandon her son), his stepmother Ann, his sisters, his stage mentor Juliette Whittaker, his collaborator Lily Tomlin, his companions and wives. In his early life, Pryor was mentored by women, not men, and this was important for me to draw out. Meanwhile the story of how abusive he’d been, as an adult with the women in his life, had been told more often from Pryor’s own point of view. I tried to change that — by documenting how that abuse was experienced on the receiving end, and by making sure that those scenes of violence had enough detail that they didn’t wash over the reader as generic. It was gut-wrenching for me to hear those stories from women like Richard’s companion Patricia Heitman, and I wanted to carry that into the writing.

Mount: Like most great biographies, your work offers readers a ‘life and times’ approach to Pryor, such that the mid-20th century changes in American society can be seen anew. While it is clear that in many ways Pryor was a product of his times, I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about how Pryor tangibly influenced America’s political and intellectual culture through his work. What would have been different for America without Richard Pryor in the limelight? Would Barack Obama’s presidency have been possible without the disarming cultural effects of Pryor’s comedic portrait of the first hypothetical black president (and the many subsequent explorations of the topic by Eddie Murphy, Dave Chappelle, Cedric the Entertainer, and most recently Key and Peele)?

Saul: Richard Pryor took a kind of black working-class brilliance — one grounded in his experience with his family and neighborhood, but catalyzed by the political ferment of the Black Freedom Movement and the experimentation of the counterculture — and he brought it to the multitudes. This had far-reaching consequences, some of which are easy to trace, some less so.

The easiest consequence to trace is in the world of comedy, where Pryor opened the big door that later comedians walked through. Bernie Mac said, “Without Richard, there would be no me,” and any number of comedians—whether black (Chris Rock), Latino (George Lopez), white (Roseanne Barr), or Asian-American (Margaret Cho) — have echoed the spirit of his words. Black comedy, female comedy, mixed-race comedy, alternative comedy — all owe a huge debt to him. Partly this was because Pryor showed how to handle the pressure of stereotype and “blow it up from the inside,” as Roseanne Barr has said. Partly it was because he opened up comedy to a range of emotion, and to a range of material, that earlier comedians hadn’t touched or known how to bring into a “comedy” act (Pryor often played with not being funny). And partly this was simply because he was a great craftsman onstage, with enormous gifts as a physical comedian, mimic, political satirist, and storyteller.

Hip-hop is the major cultural form that, burgeoning just as Pryor’s star went into decline, continued to bring black working-class struggles to a large audience, and there’s an argument to be made that Pryor seeded hip-hop through his comedy and through his work writing and acting in films like The Mack (which has inspired artists from Ice Cube and Dr. Dre to Outkast and Jay-Z). I think an enterprising scholar could write a great essay on what hip-hop took from Pryor — sometimes by sampling him — and what it hasn’t taken up in Pryor’s legacy.

As to Obama and Pryor: Obama told Marc Maron that Pryor was a favorite comedian of his, but it seems to me that he suppressed a lot of the Richard Pryor in him in order to become Candidate Obama, then President Obama. (Some might say he would’ve been a more successful President if he hadn’t!) My sense is that all those Hollywood portrayals of upstanding black Presidents by the likes of Morgan Freeman may have done more than Pryor’s routines to soften white resistance to a black President. But I would suggest that Richard Pryor’s routines drew many people into hard thinking about race, power, and violence in American history — hard thinking that had great reverberations. I suspect that, if you were to look at the music collections of the historians who wrote the books that now appear on #charlestonsyllabus or #blackpanthersyllabus, you’d find Richard Pryor represented strongly.

Mount: Given that you’ve spent considerable energy building a digital companion to your biography, what do you think is the future of the book in general and biographies specifically? Do you envision digital humanities as a permanent supplement to traditional print capitalism or might we one day live in a world where Pryor’s biography and the scholarly work that goes into uncovering him will be conveyed to the public primarily through next generation websites that are even more advanced, visual, and interactive than the one you have created?

Saul: I don’t think that there’s any substitute for a book, in terms of how powerfully it can braid together analysis and storytelling. Readers of my book, I believe, gain a more intensely realized understanding of Richard Pryor than the visitors to my website. That said, I think that companion websites can give the written work of historians a great boost — can draw a wider range of readers to a book, and can draw people into the particular work that historians do in analyzing primary sources. Matt Delmont is leading the way here, with the websites he has developed, or is developing, for his books on American Bandstand, the busing crisis, and the Roots miniseries.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

I want to thank Guy Emerson Mount for his very informative interview with Dr. Scott Saul discussing his biography about Richard Pryor. Many times when great artistry moves off of the scene of time, we forget that they were here. This interview causes one to pause and remember the greatness that was the late Richard Pryor. Thank you again Mr. Mount for a job well done and a thank you to Dr. Saul in bringing Richard Pryor back into our consciousness.