Attica: Writing on Blood, Violence, and Trauma in History

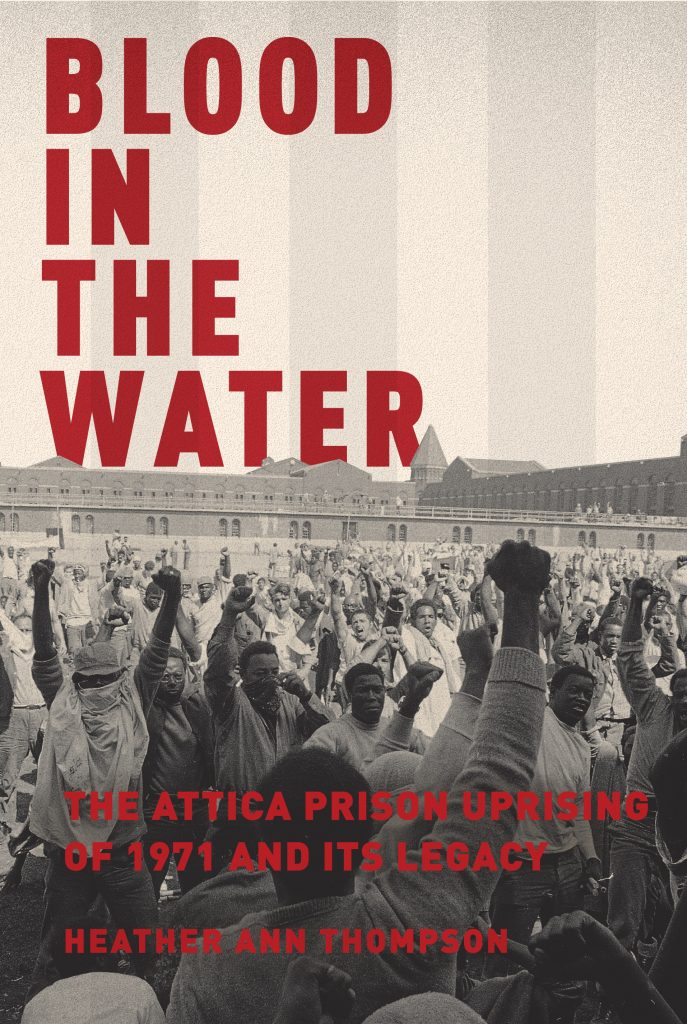

This is the first day of our roundtable on Heather Ann Thompson’s book, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. Earlier today, we published introductory remarks from Michael Ezra. In this post, historian Kali Nicole Gross surveys Thompson’s work and the lessons historians can learn when writing about trauma.

Heather Ann Thompson’s epic monograph, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy (Pantheon, 2016), at well over 700 pages, is a stunning achievement—the breadth of the research alone places it on a level rarely matched. The book’s sources include papers from the Attica Task Force Hearings, records from the Erie County Courthouse, information from the Nixon White House Tapes, reports from the New York State Special Commission on Attica and the Meyer Commission, and the personal papers of reporters and observers such as Tom Wicker, formerly of the New York Times. Organized into ten parts and fifty-eight chapters, it is an exhaustive, detailed, highly readable account of the uprising, the carceral state as it existed in New York in the 1970s, and the decades-long aftermath as victims and their families fought for answers and justice.

The strengths of the book are manifold. Not only does Thompson shed light on the brutal conditions of the institution itself but she also foregrounds the demographics of the prison population against the backdrop of the Black Power movement occurring inside and outside of its walls. Still, racism and discrimination abounded in Attica, and Thompson brings the structural elements of this into high relief when she explains: “Even though only 37 percent of the prisoner population was white, whites held 74 percent of the jobs in Attica’s power house, 67 percent of the coveted clerk positions, and 62 percent of the staff jobs in the officers’ mess hall” (p. 13). In contrast, African Americans and Puerto Ricans held 76 percent of the “dreaded and low-paid metal shop, and 80 percent in the grueling grading companies” (p. 13).

Thompson also provides a nuanced account of the prisoners’ demands, and she diagrams the lengths to which the inmates went to maintain order during the takeover, to protect captive guards, and to actively communicate with the world about their plight by asserting their humanity. The list of demands, which evolved over the course of the negotiations with officials, ultimately consisted of requests such as applying the New York State minimum-wage law to all state institutions in order to “STOP SLAVE LABOR,” to allow prisoners “to be politically active, without intimidation or reprisals,” and to end “all censorship of newspapers, magazines, letters, and other publications coming from the publisher” (p. 79).

Thompson also provides a nuanced account of the prisoners’ demands, and she diagrams the lengths to which the inmates went to maintain order during the takeover, to protect captive guards, and to actively communicate with the world about their plight by asserting their humanity. The list of demands, which evolved over the course of the negotiations with officials, ultimately consisted of requests such as applying the New York State minimum-wage law to all state institutions in order to “STOP SLAVE LABOR,” to allow prisoners “to be politically active, without intimidation or reprisals,” and to end “all censorship of newspapers, magazines, letters, and other publications coming from the publisher” (p. 79).

Prisoners also wanted healthier food, easier access to healthcare, improved educational programs, and an end to administrative resentencing for inmates returned for parole violations. Indeed, Thompson is at her best when she shows how otherwise-minor infractions and subsequent parole violations could land nonviolent offenders in harsh sentences at Attica. Thompson also sees the Attica episode through to the bitter end—following victims’ and their families’ decades-long struggle for, if not justice, then closure in the wake of the bloody siege led by New York State troopers determined to reclaim the institution and to punish rebelling prisoners. Thompson also shows how in the immediate aftermath, prisoners faced a litany of charges for their roles in the uprising, but as The Nation reported, “Despite the fact that ten hostages, as well as twenty-nine prisoners, died from the state’s gunfire, the grand jury has not yet found sufficient cause to indict a single trooper, or guard” (p. 307).

But while the state may have been hesitant to find fault with troopers, Thompson guides readers unflinchingly through the shocking brutality that punctuated the violent retaking of Attica. It is important to note that Thompson does not forward a sanitized image of the prisoners. In mapping the uprising, she depicts a chaotic scene that pitted prisoners against guards but also revealed how prisoners attacked each other. Nineteen-year-old twins John Schleich and James Schleich, in Attica for parole violations, were themselves victimized during the bedlam of that morning. In attempting to rescue his brother, John was held at knife point and repeatedly gang raped by five or six men. James was also raped, as John could see him “up against a wall, some guy behind him” (p. 65). Prisoners also raided the commissary and looted drugs, while others used the uprising to settle old scores with each other. Still, as Thompson writes,

A bloody outcome was virtually guaranteed by the NYSP’s choice of weaponry. . . . The men leading the assault on D Yard would themselves be armed with .270 caliber rifles, which utilized unjacketed bullets, a kind of ammunition that causes such enormous damage to human flesh that it was banned by the Geneva Conventions.”

The retelling that follows is a harrowing—and at points a downright sickening—account of the violence visited on prisoners by troopers and corrections officers. Chapter 21, “No Mercy,” vividly describes how prisoners’ bodies were opened up by gunfire from rifles and shotgun blasts. With tear gas heavy in the air and a fuselage of bullets clouding the sky, prisoners like nineteen-year-old Melvin Marshall, in Attica on a parole violation, lay on the ground, gasping for air, while a “trooper kicked him and brought a gun butt crashing down on his head” (p. 184). Another young man, twenty-one-year-old Chris Reed, had been shot four times—one bullet removed a chunk of flesh from his thigh. On top of his injuries, Reed was forced to listen as “troopers debated in front of him whether to kill him or let him bleed to death” (p. 185). During the course of said debate, the troopers took turns jamming their rifle butts into his injuries and “dumping lime onto his face and injured legs, until he fell unconscious. When he awoke, he found himself ‘stacked up with the dead bodies’” (p. 185). The final tally of men shot was 128.

Rage and hatred become palpable on the pages of this book as officers called prisoners “niggers” and threatened to kill them. Yet the benefits of death may well have rivaled that of survival. Surviving prisoners of the uprising were subject to cruel torture in the days after the retaking: “Russian roulette was a frequent practice of the night guards and troopers” and thirsty, exhausted men who cowered on cold floors were told to “drink the urine of corrections officers” (p. 216). As one prisoner was dragged down the stairs, “he almost slipped and fell on a large puddle of blood with broken teeth in it” (p. 215). Frank “Big Black” Smith, considered one of the ringleaders of the uprising, endured special torture, being stripped and beaten for hours; Smith was struck “repeatedly between the legs and in the anal area” (p. 215).

The carnage is chilling, and the book’s descriptions are graphic. Readers come face-to-face with the blood, sweat, piss, and stink of Attica. It’s a rot that is unshakable, particularly for the victims who suffered it. Chapter 56, “Getting Heard,” attempts to map the long-lasting impact of the uprising and its tragic end, as surviving hostages continued to struggle with anger and depression, nightmares, ongoing health issues and substance abuse problems; many tried to cope by self-medicating (p. 534). The pain of spouses and children who lost loved ones is also revealed as Carl Valone’s widow spoke of the trauma her family suffered after the loss of her husband. Valone recounted how her son, who took his father’s death especially hard, eventually “hanged himself” (p. 537). Less legible is the sustained trauma of Attica’s prisoners, though there are snatches of it in surviving testimonies of men like “Big Black.”

Despite the fact that many of Attica’s prisoners and victims were black and Latino, the prevailing voices driving the book are those of white men, whether it’s journalist Tom Wicker or sparring attorneys such as Louis Aidala and William Kunstler or whistle-blower Malcolm Bell. The centrality of white men’s voices here may gesture toward the limitations of the archive vís-a-vís race and power but also it points toward the dearth of historical models that show black bodies as victims of bloody carnage as well as emotional and psychological trauma. Or put another way: while extensive examples of physical brutality being meted out on black bodies abound in history—indeed, most works wrestle with this issue—too few works adequately address the interiority of black trauma, particularly when it comes to state-sanctioned violence. Meaningful intervention here is essential to continue affirming black life and making visible the full extent of the state’s crimes against black humanity.

All told, Heather Ann Thompson’s Blood in the Water is a powerfully written, meticulously researched, jarring account that is poised to become the defining work on the legacy of Attica.

Kali Nicole Gross is Professor of African American Studies at Wesleyan University. Her research concentrates on black women’s experiences in the United States criminal justice system between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. She is author of the award-winning book, Colored Amazons: Crime, Violence and Black Women in the City of Brotherly Love, 1880-1910, and the newly released, Hannah Mary Tabbs and the Disembodied Torso: A Tale of Race, Sex, and Violence in America. Follow her on Twitter @KaliGrossPhD.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.